This Pendleton Institute Is a Beacon for Native Art

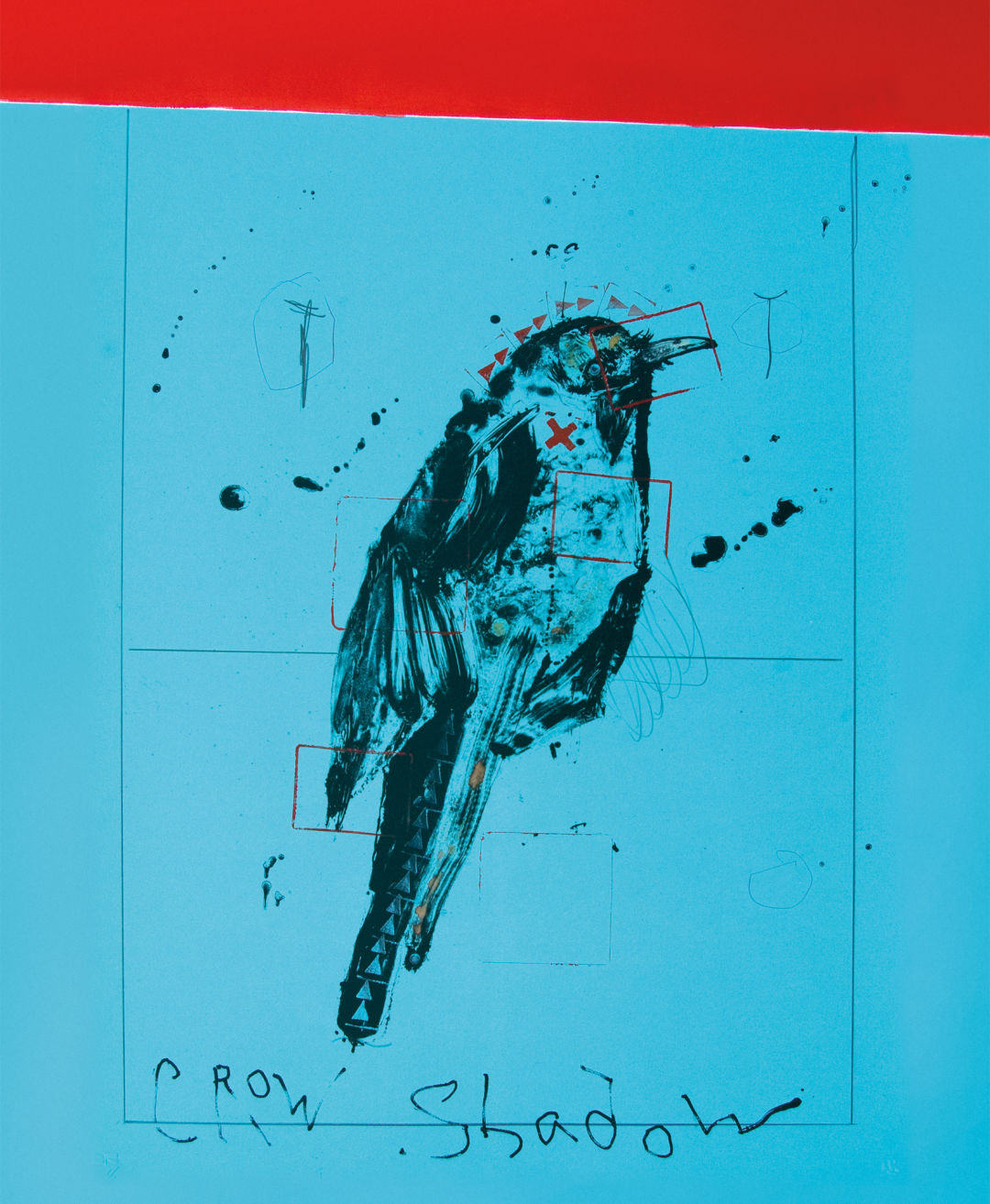

From Rick Bartow’s Crow Shadow monoprints series.

Nine and a half miles east of Pendleton, turn onto St. Andrews Road. Drive through flat, vast country, just past the sign that says “pavement ends.” There, in the heart of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla reservation, an unassuming, two-story stucco building is the unlikely home of a professional print studio and artist space that’s getting national attention.

Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts has fostered Native American art in Oregon for more than two decades, helping make the state a stronghold of modern Native work. Big names in the art world, such as Rick Bartow and Kay WalkingStick, and rising stars like Jeffrey Gibson and Wendy Red Star are among the hundreds who have created art in the 5,500-square-foot space. Work from Crow’s Shadow has graced the Portland Art Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, and the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe. Last summer, the Library of Congress bought 18 prints created here.

In short, in its 25 years—celebrated this month—Crow’s Shadow has gone from a local rallying point to a national resource. It owes its existence to painter James Lavadour, who in 1992 was just starting to make a name for himself with his intense, elemental landscapes. As he experienced more success, however, the enrolled member of the Umatilla tribe also became more aware of the obstacles Native artists face. “As I began exhibiting and understanding the way the art world works,” he recalls, “I realized that all of those things that make up a vibrant artistic community were missing here.”

He approached friends, secured a grant, and Crow’s Shadow was born, with his former studio—complete with leaking roof—as its headquarters. “We did everything under the sun for artists,” Lavadour recalls of an organization initially defined as an economic incubator for the reservation’s artistic community. “We did branding, all kinds of professional development, résumés, marketing, workshops. And the way we operated at that time was just to invite an artist in and we’d put on a workshop.”

The artists who came in would make prints on Lavadour’s own press. He saw the economic and artistic potential in printmaking, and Crow’s Shadow began a search for a master printer. In 2001, Frank Janzen, who trained at the influential Tamarind Institute, came on board. Under his command, Crow’s Shadow amassed a permanent collection of about 230 framed prints, with hundreds more for sale online.

Clockwise from top: Frank Janzen at work in the studio; artist Samantha Wall signing prints with Janzen: a field in front of Crow’s Shadow

Over the years its rudimentary quarters have been renovated to a brightly lit space housing a gallery and the print-making studio. But the operation is quickly growing too big for the building, which it occupies “at the pleasure” of the Catholic-run St. Andrew’s Mission.

“There’s a long-term goal of building a new building ourselves,” says executive director Karl Davis, as he describes plans for expansion of the artist-in-residency program and the existing studio space. Already, says Davis, Crow’s Shadow is in a league of its own. “There’s no other professional print studio on a reservation in the United States, to my knowledge,” he says. “It’s one of a kind.”

Lavadour is ready to push that advantage.

“We’d like to be a center for indigenous arts—a national center where we can invite indigenous artists from anywhere in the world to come here and work,” he says.

“My dream is to be able to bring really creative people together and create some sort of new thing,” he continues. “You have your technology and you have your building, and then the art of bringing people together and seeing what happens—that’s going to be exciting.”