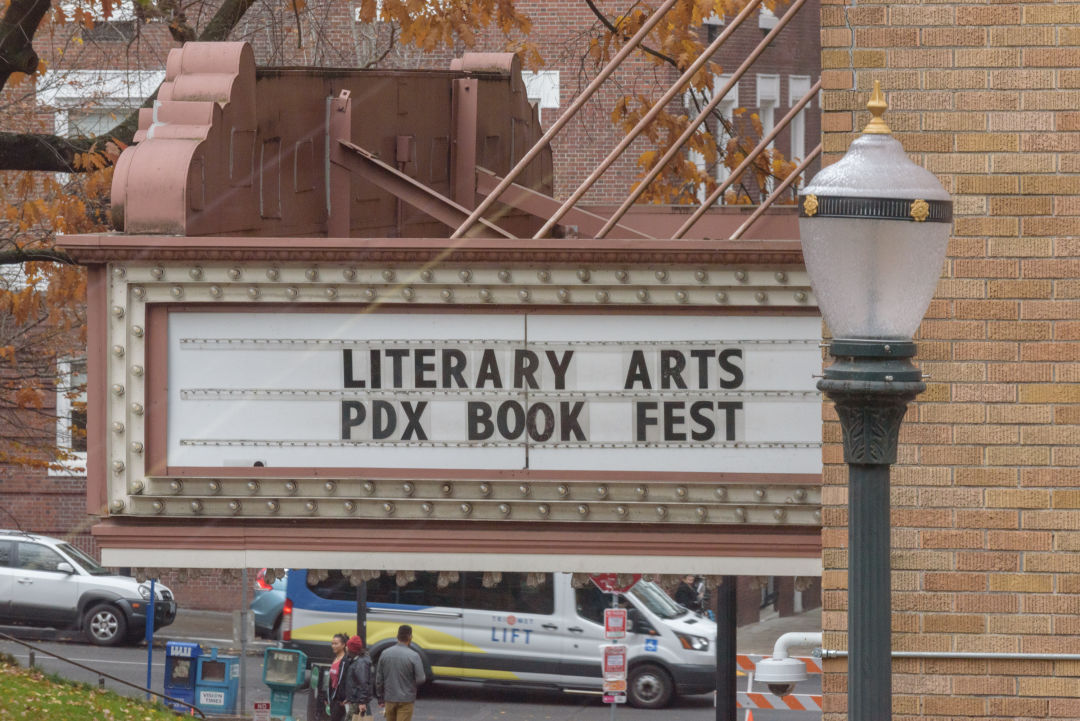

The Portland Book Festival Is Good for More Than Just Meet Cutes

Image: Andy Petkus

Forgive me if we, as a culture, have divested from meet cutes—as a young, gay, bespectacled journalist who used to live in the woods and has seen You’ve Got Mail so many goddamn times, they are an outdated holdover that I refuse to relinquish. They are my emotional appendix.

The Portland Book Festival, presented by Literary Arts and renamed from the eons-more-fun “Wordstock,” slid comfortably into its 15th year on Saturday. Hundreds of writers who’ve made it, writers who haven’t, writers who are somewhere in between, and non-writers who love writing gathered on the South Park Blocks for a nine-hour marathon of panels, readings, signings, and discussions. True to form, meet cutes abounded.

Local heavyweights like Mitchell S. Jackson and Kimberly King Parsons met cute with pieces at the Portland Art Museum as they and others performed short pop-up readings throughout the day (Jackson spoke about race and masculinity in front of Hank Willis Thomas prints that read “Be a Man”; Parsons read her sordid, female-focused tales by a painting called Girl with Cigarette). Strangers approached each other on museum steps and park benches, driven to conversation by copies of the latest Zadie Smith or Kristen Arnett; kids met soon-to-be-beloved titles in the cramped-but-cavernous halls of the event’s multi-venue book fair.

The new guard joined the old. Malcolm Gladwell spoke at the same event as a panel of YA graphic novelists. Plenty of unexpected pairings swirled around the space, and the major takeaway seemed to be this: we should all spend more time listening to people whose only job is to think.

Bouncing from panel to panel, interview to interview, reading to reading, it highlighted how rarely we get to steep ourselves in ideas that aren’t presented in the name of material gain. A few hundred people piled into the First Congregational Church to hear Tim O’Brien talk about fatherhood, and we weren’t expected to take what we learned to increase value for our shareholders or become more efficient managers. This was not a corporate conference. It was an opportunity to learn from people who’ve made it their business to thoughtfully talk about how we live.

On that note: O’Brien brought his audience to tears more than once in a bright, candid conversation with OPB’s Dave Miller. He shared a story from his latest (and final) book about a family vacation in France that ended in epiphany. (“I’m in a church. I feel like a minister,” he deadpanned, answering his sixth or seventh question with an illustrative anecdote.) Elsewhere, he gave weight to charmingly mundane musings on fatherhood by linking them to his experiences in Vietnam—paternal love, for example, surrounded him “like gunfire.” He prizes skepticism in his sons, because "absolutism can kill people. I've seen it happen."

An especially rich late afternoon panel brought together poets Diannely Antigua, Jericho Brown, and Malcolm Tariq at the Winningstead to discuss the ways they write about desire. "My pussy can't be alone for more than a month," went one of Antigua's poems. "What if the ancestors are watching us fuck?" asked one of Tariq's.

Jericho Brown, Malcolm Tariq, and Diannely Antigua on the "Dangerous Love" panel.

Image: Andy Petkus

After a series of thoughtful questions (and one fairly cheap one about how the 2016 election did or didn't influence the poets' work), the conversation blossomed into a meditation on the differences between pleasure and joy and the responsibilities poets have to tell the truth: "I would hope you'd do that as an adult, but we don't," Brown said, grinning. "That's why we need poets."

The Book Festival is the engine for a thousand meet cutes, sure, and an opportunity to hear from your heroes (should your heroes spend most of their time at the keyboard with a flickering cursor). But it's also necessary in a way that doesn't underline, and thus undercut, its own necessity. We need events like this, where massive crowds look on as the poets take a break from their poems to remind us with a smile why they write them in the first place.