Beckett Women Is a Mesmerizing Scream

Image: Owen Carey

In the first episode of Big Little Lies’ second season, Meryl Streep delivers one of the misguided project’s only effective moments. Clad in a mousy wig, false teeth, and comic-book-mad-scientist glasses, she closes her eyes and shrieks. She’s mourning (the season’s flimsy concept hangs itself on the death of her son) but she’s also defending her right to mourn. In her eyes, everyone around her is cold and unfeeling; she’s demanding dignity for her anguish.

Beckett Women, the latest piece from the Portland Experimental Theatre Ensemble, has similar demands. Director Rebecca Lingafelter weaves together four short plays by the enigmatic Irish master; the first, Not I, is a discursive monologue delivered with jaw-dropping discipline by Cristi Miles. Using nothing but her disembodied mouth—everything else is obscured by a proscenium-length black curtain—Miles describes a series of disconnected vignettes, some idyllic, some distressing. Then, out of nowhere, she screams. It’s an honest, soul-deep, Meryl scream, all the more chilling because we can’t quite pinpoint what prompts it.

As the show rolls on, we get closer to the source. Each of Beckett Women’s four parts paints womanhood as a prescribed, rigid condition. The narrator in Not I, apparently unaware she’s just a mouth, frets at the idea of being reduced to “the mouth alone”; the characters in a short called Come and Go speak in stilted gossip, like they’re being controlled by an offstage codeine-addled Bravo producer. Two other pieces, Footfalls and Quad, feature women who can only move in strict, linear patterns, doomed to perform this dull choreography until they learn to chart their own paths.

Spoiler alert: they figure it out. Per the director’s note, the show is structured around a symbolic return to Eden. At the end of each section, bits of set fall away piece by piece until the characters find themselves in a lush, actual garden.

Being Beckett, the text is so dense that it's easier to digest on a sensory level than an intellectual one—about 30 minutes in, you're basically thrown into a meditative state. Some might fairly call it tedious, but I found it thrilling, not least because it meets PETE’s exceptionally high technical standards.

Image: Owen Carey

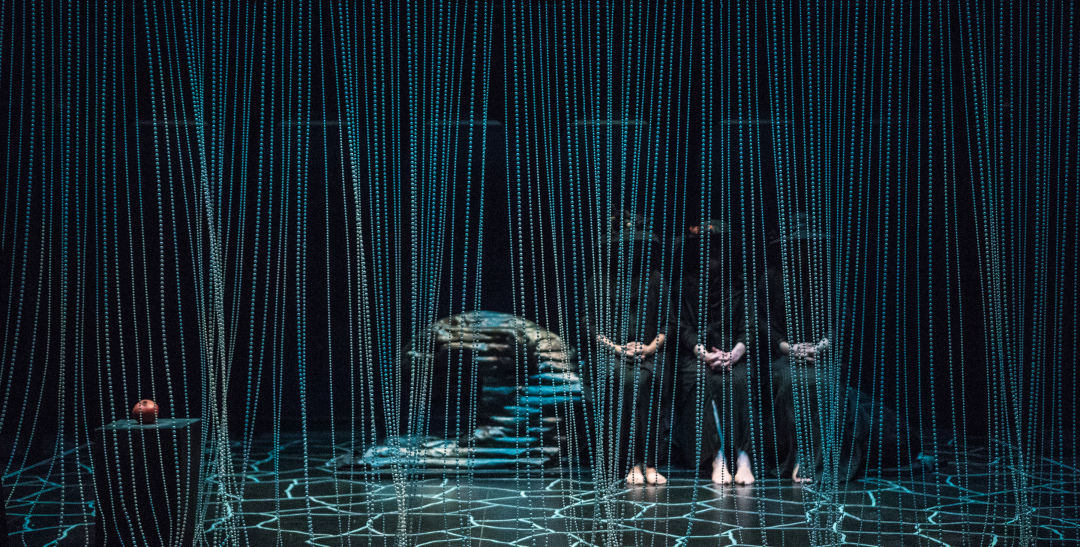

The scenic design, by Peter Ksander, is breathtaking: an occult mystery box that keeps shedding parts. Mark Valadez's sound design stitches a thousand industrial whirs into a sort of machinist lullaby. Miranda K Hardy's lights hold us at an icy remove until it's time for explosions of color, and Amber Whitehall's movement direction functions similarly, requiring stiff precision and then raucous release from the cast.

And what a cast it is. Miles gets the lion's share of text, and she finds surprising emotional levels in language that could easily drown any seasoned performer. JoAnn Johnson, Chantal DeGroat, and Rose Proctor get far less dialogue, but still command attention with their physical work. In the home stretch, all four women break out into a hair-raising rendition of "The Garden" by German experimental group Einstürzende Neubauten, and the harmonies are tighter than in any number of professional musicals I've seen this season.

Beckett Women is not an easy show, and I'm not sure it's a fun one, but that difficulty is part of its appeal. In less-skilled hands, it might come off like an exhausting MFA thesis. In PETE's, it's a probing look at how to live in a world that would reduce you to little more than a mouth; it subjects you to tedium and confusion and a sense that nothing works as it should before imagining a world where things might. It's a scream that connects.