Portland Author Willy Vlautin Talks Gentrification and the Changing City

Willy Vlautin counts cranes. Or at least he used to, when they first started springing up across the Portland skyline. “For a few years, there was between 10 and 15 cranes going at a single time, and at the same time in St. Johns—my favorite place in the world—I started noticing all these weird mom and pop shops start to disappear,” he says. Those that owned their buildings were selling up in the property boom, but if they were tenants, “their rents suddenly doubled and they got kicked out and they couldn’t navigate the next level of gentrification.”

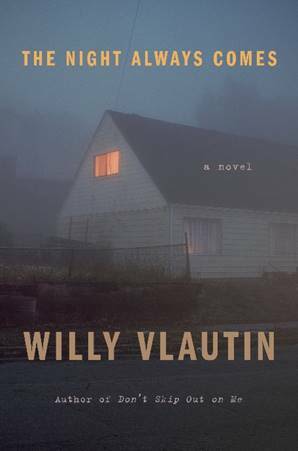

Thoughts like these coalesced into The Night Always Comes, the newest novel from Vlautin, an acclaimed musician (onetime frontman of the late Richmond Fontaine and now a member of country soul band the Delines), writer, and one of the nicest people you’ll ever meet. In traditional Vlautin vein, his sixth novel is unsparing in its depiction of the grim realities of financial struggle and loneliness. It’s the story of 30-year-old Lynette, who works multiple low-wage jobs while caring for her developmentally disabled brother and struggling to keep her head up in a PCC accounting course. She’s saving to buy the crumbling house she lives in with her mother and developmentally disabled brother, knowing that the alternative is to lose it and any chance of owning her own place in a rapidly gentrifying city.

“Lynette still believes that she can get her family to survive this gentrification. And she can still be a part of her community and have power,” says Vlautin, who says he bought a $72,000 house in Southeast Portland some 20 years ago, a purchase that changed his life. “I liked myself better, I started staying home more. I mowed my lawn, I bought furniture. I just was like, ‘Hey, I'm not a bum. You know, I thought I was a bum, I felt like a bum, but I guess I'm not.’ So it was really exciting. But that can't happen today.”

In Lynette’s way is bad credit and a mother who has given up on trying, their combined forces pushing her off the licit path towards a slew of grifting and desperate characters. “I was interested in something President Trump said,” says Vlautin. “Which was, ‘The point is you can’t be too greedy.’ And I started thinking about that in terms of OK, we know from the 2008 crash what greed looks like from bond traders and CEOs and bank executives.” So how, Vlautin wants to know, does that philosophy of acquisition affect the people at the bottom of the American food chain? “If capitalism is a bigger part of America than community,” he asks, “how's that going to look?”

In the end, all the right moves from Lynette still can’t save her home, or her family, her fate playing out fears Vlautin developed as a kid growing up in Reno. “I was raised to believe that you're only like two or three bad moves away from living in your car. So don't screw up,” he recalls. “My mom was so worried about that. She was just like, you just get a job, and you just stay, and no matter how bad it is, and no matter how difficult your life is, you just got to stay because you might never get another one.”

His family was conservative, and Reno “a kind of tough city to be a weirdo in,” but a trucking company Vlautin worked at transferred him to Portland when he was in his twenties, where he found a network of artists and musicians with home he connected. The rest is the stuff of Portland nineties lore: Vlautin formed the internationally acclaimed Richmond Fontaine soon after his arrival, and also found real success as a novelist—Irish writer Roddy Doyle has described him as “one of America’s great writers,” he’s won several awards and seen two of his books translate to the screen—placing a new novel into the world every two to four years since The Motel Life first hit shelves in 2006. And even as The Night Always Comes makes its way to readers, he’s already got something new on the go—no accident when it comes to his writing process. “The second I stop something, then I lose confidence and confidence has always been my Achilles heel,” he says of his drive to keep sitting down at his desk in his St Johns office to write. “I have to really guard against that. If I read Flannery O'Connor, I quit writing. It always devastates me. Like if I read a short story or hers, then I always quit for a while, because I'm just like, what’s the fucking point? You're an idiot!”

Yet still he talks about writing with a straightforward and contagious joy. “It's my favorite thing to do, is writing. I'm lucky that way.” It’s how he talks about Portland too, his arrival here one of the strokes of great fortune in his life, even while he mourns some of the changes of recent years and wonders how we’ll all emerge from this time.

“Portland's always been really good to me, and I've always loved it. It's just, it's going through a really interesting growth spurt. It's scary,” he says, as straighforward and sounding momentarily like a character in one of his own books as he grapples with what it all means. “I don't really understand it. It just makes me kind of shaky and nervous.”