Portland Comedian Riley McCarthy Thrives on Discomfort

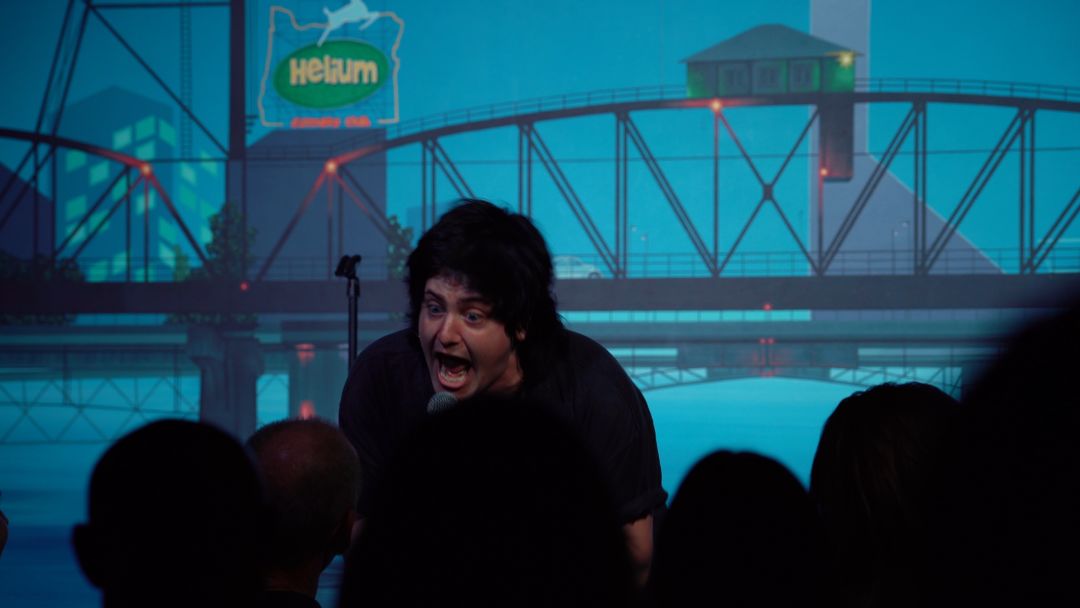

McCarthy performing at the 2021 Portland's Funniest Person competition at Helium Comedy Club

Image: Randall Lawrence

In the summer of 2018, Portland comic Riley McCarthy checked out of Unity Center Behavioral Health’s inpatient program, went home, took a shower, and headed to Helium Comedy Club to perform a set. It was the semifinals for the Portland’s Funniest Person competition, and McCarthy had just moved to town that year, fresh out of college and suicidally depressed.

With a few years between then and now, McCarthy describes Unity in his sets as “an underfunded, understaffed mental health facility with the vibe of a well-funded, overstaffed haunted house.” One he returned to for group therapy, outpatient sessions with therapists, and material—a way to process his own trauma and turn his experience into something universal.

This month, McCarthy returned to Helium to compete in Portland’s Funniest again; this time, he took home second place. As ever, the comic is motivated by his own discomfort, energetic and exuberant onstage even when talking about grief, impotence, depression, and (almost) fighting a neo-Nazi in a Plaid Pantry parking lot.

We sat down with Riley to talk about his successful Bob Ross-adjacent Twitch show, what makes him uncomfortable, what motivates him, and what makes him laugh—especially the dark stuff. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

PORTLAND MONTHLY: How did you get into comedy?

RILEY McCARTHY: I was always a big fan of stand-up as a kid. My father was a huge comedy fan and I would get stand-up albums for Christmas every year—Steve Martin (my first love), Mitch Hedberg, Mike Birbiglia, that kind of early 2000s stuff. I went to school for short fiction and printmaking—very lucrative, I know—and I did an MFA residency at the end of my undergrad in playwriting; I wanted to write short fiction and nonfiction. But when you write short stories, it’s hard to tell if they’re any good, because the only people that will read them are your friends. Comedy was something I always wanted to try, and I immediately fell in love with the process, the feedback loop of constantly workshopping. The audience will tell you if your fucking joke sucks.

As you started to step into stand-up, were you thinking about writing jokes in a similar way [to short stories]—thinking about narrative arc—or were you essentially building from the joke up?

It’s kind of funny, my heroes as a kid were Emo Phillips, Mitch Hedberg, and Demetri Martin, so I really wanted to be a one-liner comic. It turns out I can’t write a one-liner to save my life. That form is like math, you really have to have a keen mind for syntax and economy of words. So I was trying to do these one-liners, bombing every time, and I just tried to tell a story. It was the first joke I had that worked.

What brought you to Portland?

I was living back home with my parents in Wisconsin, and just from being a comedy fan, listening to podcasts and reading interviews, I’d always heard that Portland was a phenomenal place to get your start. I came here with no job, I didn’t really know anyone out here. It was a great decision because it forced me to go, ‘Well, I have nothing else to do out here, I might as well focus on stand-up.’ And it really is a phenomenal city for a comic starting out: There are open mics and showcases every night of the week, you can perform as much as your body will let you. My first year, there was a week where I did 14 sets. I don’t think you could do that in most places.

In the last year, it’s been a lot harder to go workshop sets, because you’re not able to perform in live settings. How did that impact your ability to prep for something like Portland’s Funniest?

Massively. For a storytelling joke to work, it has to have a thesis, something relatable that ties it all together. And when I’m writing a story, I almost never know what that thesis is when I start. It isn’t until I am performing it that I start seeing what people are responding to—I really do think that in stand-up, 90 percent of the work is done in the redrafting process.

For instance, I tell a story about being in outpatient after a suicide scare, having someone mistake me for a doctor. When I wrote that joke first, I had it in my head that it was a story of the absurd banality of surviving a crisis when the recovery process becomes as boring as the day-to-day. But it wasn’t until I started performing that joke, until I saw how people were responding to the stuff about lying about being a doctor, that I realized, ‘Oh, this is a story about what it’s like to be caught up in a lie. That’s what’s universal there.’

That story is from, likely, a deeply challenging part of your life. How did you get to the point where you were able to find the humor in your experience there?

I am pretty good at finding humor in things. I think it’s a really crucial defense mechanism that people with mental illness develop. It was a very absurd situation—the first time I went to Portland’s Funniest semi-finals, my round was the day I got discharged from Unity. I definitely thought that was very funny. When you’re in those moments of true crisis, the easiest way to keep a handle on something steady, to keep your head above water, is to find the humor in it. It’s such an illogical, chaotic thing that’s happening to you, I think humor is crucial to survival. The past two years have been kind of a crash course for neurotypical people in what isolation means, in what alienation means. So I imagine people are more savvy to that sort of narrative.

Image: Courtesy Riley McCarthy

During the pandemic, you started your Twitch series, Riley Paints His Friends. Where did you get the idea for it?

It’s an idea I’ve had for a while, but it wasn’t an idea I’d pull the trigger on if it weren’t for the pandemic. I went to school for writing and art, and I always wanted to do this Bob-Ross-type thing. When the pandemic started, when everyone was going, ‘How do I produce content?’ I said, ‘I guess that’s a skillset I could use.’ But I don’t really do landscapes or still life; I really do portraiture. The obvious thought was, ’Well, if I’m doing portraits of people, I might as well have them on, too.’

People really seemed to identify with how vulnerable it was. We would talk about mental illness and grief and fear and all that stuff. Right now, the show is on a break—obviously I wanted to focus on stand-up the second I could do it again—so the Twitch show was something like season one. Now, I’m working on revamping it into a live show that’ll kind of be like a late-night-style interview show: I’ll have three comedians on, we’ll do 15 minutes of stand-up and 15 minutes of interview, all while my painting is being projected. If you book people that you trust who are talented and funny, and you create a trusting, low-pressure environment, you can count on humor to come. Funny people talking about compelling stuff I find more engaging than funny people forced to talk about funny stuff.

When you’re onstage, you don’t shy away from sharing pretty intimate parts of yourself, including your experiences as a queer man. Some people say that being a queer comic telling overtly queer jokes onstage is an inherently political act, in that it forces people to recognize and interact with queer identities and culture. Would you agree with that?

I never go out of my way to write anything political. I actually try to avoid topical humor as much as possible, because I think I want my work to be very human; I want it to be relatable to anyone. But in doing personal stories, I’m very comfortable with my life being politicized by an audience, as long as I’m presenting it in an honest way without an agenda. People can draw their conclusions from there, take what they want from that.

I’m hesitant to talk about queer issues when it comes to comedy. Being a cisgender bisexual man, I have a lot of privilege that comes with bi erasure, as a bisexual performer. I’m not saying bisexuality is a privilege, but I have the privilege of not always being thought of as a queer comic. I’m a comic who’s queer. If you asked someone to name 10 gay celebrities, they could fire some off. If you asked someone to name 10 bisexual celebrities, they’d probably stop to think about it. If you started naming them—Ezra Miller, David Bowie, Carrie Brownstein—people would go, ‘Oh, yeah, of course.’ It’s the privilege of people thinking of them as an artist first.

Tell me about Magical Tea Party.

It’s a queer Dungeons & Dragons comedy show, live-streamed by Curious [Comedy Theater] and played in front of an audience. We’ll be playing the same characters every episode, it’ll be an evolving story, but every show will be in its own bubble so if you haven’t seen any of the other ones, it’ll still make sense.

Comedians, typically, whether they want to admit it or not, are huge fucking dorks. D&D is a game that engages the imagination really actively; to want to do stand-up comedy, you have to be someone who lives in your own imagination.

What do you think defines Portland comedy?

There’s a lot of optimism in the comedy scene here. Obviously it’s competitive, because you know, we live in a competitive world and a capitalistic society, but I think it’s a healthy form of competition. I see comedians I love doing better and I want to do better. I see Tory Ward or Lydia Manning do a set, and I go, ‘Fuck, that’s one of the best sets they’ve ever done, I want to get to that level.’

What inspires you?

Curiosity and fear. (Laughs.) We’ll go with that.