Come On In at PICA Is a Disorienting Trip inside Our Own Bodies

Faye Driscoll's Come On In, as presented at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis

Image: Bobby Rogers and Courtesy Walker Art Center

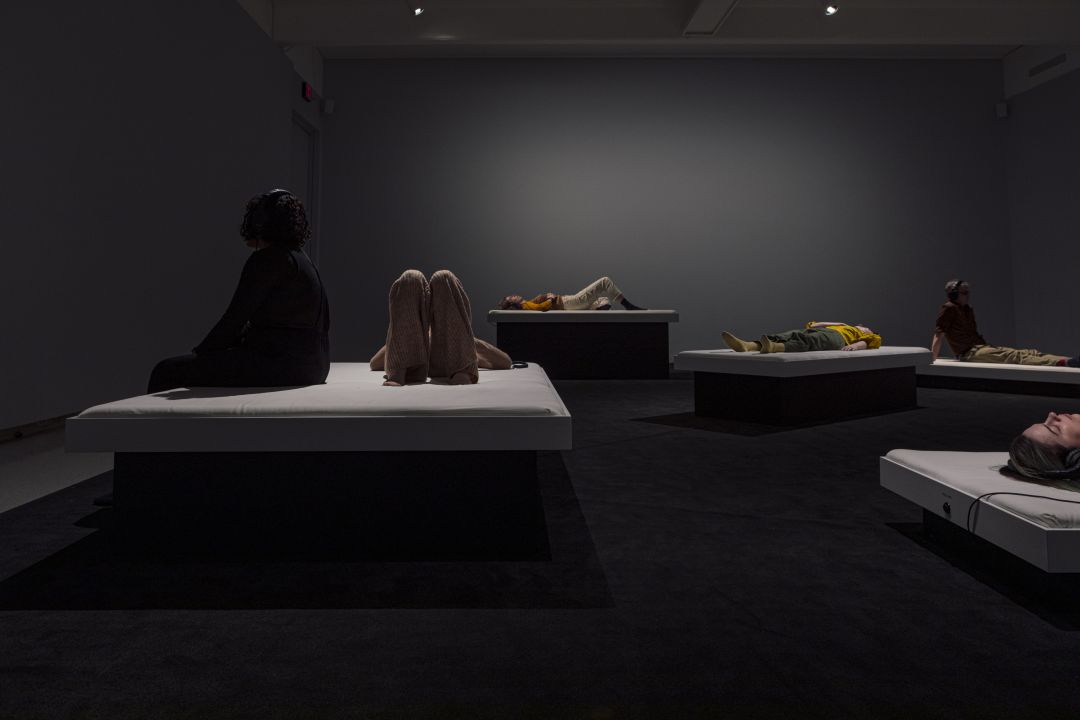

The warehouse is dim. Against the back wall, lights pulse soft and low, providing faint drips of color. Before me are five white platforms, each at a different height and angle. On three of them, people lie supine and still. One stretches a bent leg straight. Another moves a hand to their belly. Lit from above, they resemble nothing so much as sculptures on pillow-top pedestals.

I tug off my boots, slide them into a cubby, and step onto a rug. I pad to one of the platforms and sit. At one end rests a headset. I pull it over my ears, press a silver button, and lie back.

“Make yourself really comfortable,” a voice says. “Lay down.” I shift, adjust my neck, wish for a pillow. “I want you to imagine you are being held by someone who can’t get enough of you. They absolutely adore you and you’re falling, falling, falling into their arms.” The voice drops to a whisper: “My angel, my angel, my angel.”

That voice belongs to Faye Driscoll, the New York–based artist who created Come On In, running at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art through January 15. Part performance and part exhibition, Come On In leads attendees through a half dozen different audio recordings, which are collectively titled “Guided Choreography for the Living and Dead,” and are like mindfulness exercises gone a little batty. Driscoll leads you through some breathwork, draws your attention to your feet, you know the drill—but then she loops through language in a way that verges on incantation, delighting in sound over logic.

Over the next six or so minutes, Driscoll’s voice takes me on a curious sort of body scan, inviting me to see my fingers as chunky sea worms and my fingertips as old, shriveled faces. My tongue becomes a slug, slathering and sliming in my mouth. I become a tiny bunny rabbit, melting, melting. At some point I’m asked to feel the palms of my hands, then the palms of my feet. With repetition, it becomes a hypnotic refrain: “the palms of your hands and the palms of your feet, the palms of your hands and the palms of your feet.” Then I’m asked to feel the palms of my pelvis.

The palms of my pelvis? I could become a bunny rabbit, could accept that feet have palms, but the palms of my pelvis—this, for me, is somehow a step too far. Driscoll’s voice, though, continues to pulse: “the palms of your pelvis.” I resist, resist. Then I find myself noticing how the p’s seem to pop against my ear. The s’s, meanwhile, almost hiss into my head. With some reluctance—and a bit of relief—I give over to Driscoll’s voice.

Sometimes she asks me to touch my face, lift my arms, or rise to a seat. But more often her steering is off-kilter, asking me to make odd leaps of the imagination: How do I feel the inside of my face? How do I crack it open like an egg? Must I again picture my fingers as chunky sea worms?

“I started out this piece by speaking it,” Driscoll told me in a phone call earlier this week. “It was quite exhausting, because I would then record it and do the body scan myself, so I was in these very strange headspaces, often for hours.”

Driscoll is a dancer and choreographer, so she spends a great deal of time moving her own body and directing other people to move theirs. She’s developed her own kind of vocabulary, and the meditations in Come On In can feel like eavesdropping on the studio. They are also intensely intimate: Driscoll asks you to draw your attention not just to your pelvis but to your pubic hair, to your saliva and sweat and tears, to your snot and egg and cum and scum and mold. (Mold?) And with her keen vocal modulations—dropping into a whisper or whipping from honeyed to sharp—she draws attention to the fact that there is no voice without the body.

On our call, Driscoll referred to the voice as an “ancient technology.” She went on: “We know it so well. We know how to read a tone. We know instantly, when we get on the phone with a friend, what’s going on. That tone and that heat and that resonance, and all the things you read from the body, it’s the most direct way in.”

Indeed, what makes Come On In so intimate is less its mention of body parts we’re told not to discuss in polite company than the private experience Driscoll’s voice creates for the listener. The headset covers your ears only. No one else knows what you’re hearing. No one else knows that in this very moment you are thinking about your nipples.

Except, of course, you’re in a room with other people who are also being asked to think about their nipples. Driscoll has put us alone together in a way that feels very pandemic-appropriate but actually predates our current era. Commissioned by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Come On In first opened on February 27, 2020. It closed two weeks later. In the wake, Driscoll worked with the Walker to build an online experience that leads visitors through the exhibition, even giving them a track to listen to at home. But its resurrection in full, live form—the show had a run at Seattle’s On the Boards before arriving in Portland—has moved Driscoll. “It’s occupying a physical space, and maybe only a few people [come a day], but there’s a gravitas to that,” she said. “It’s not in this anything-is-happening-at-any-time, context-collapse space that is the internet.”

During the pandemic, Driscoll has entertained new questions about the body and technology. A few of the audio pieces in the Portland version of Come On In are reworked, including one called “Search Engine” that teems with the language of screens and apps and algorithms. I found myself almost itchy while listening, eager to be out of it and alarmed when I sat up and saw a fellow attendee sitting at the cubbies, hunched over his phone. Driscoll likes to traffic in sensory overload (her live performances, including one that came to the Time-Based Art Festival in 2017, can include boisterous interactions with the audience), and at times the tracks in Come On In feel like floods that won’t stop. Which, of course, is also how the internet sometimes feels. (A good companion read would be Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This, which asks similarly big questions about how the internet has warped the way we perceive and experience our bodies, and does so in torrents of language.)

At some point during my visit, I realized I was darting from bed to bed, treating each listening station as if it were an assignment to be checked off a to-do list. I paused, removed the headset, and noticed how my whole torso felt lighter. An ambient soundtrack—the hum of a drone, a sporadic clank—seemed to reset my ears. I blinked open my eyes, which had adjusted to the darkness, and saw someone lying on the carpet. Someone else was making woozy twirls across the floor.

Oh right, I thought. The bodies. Here they are.

Come On In

Various times through Jan 15, PICA, $0–20