Oh, Rose’s Olivia Rose Has a Lot of Problems Still

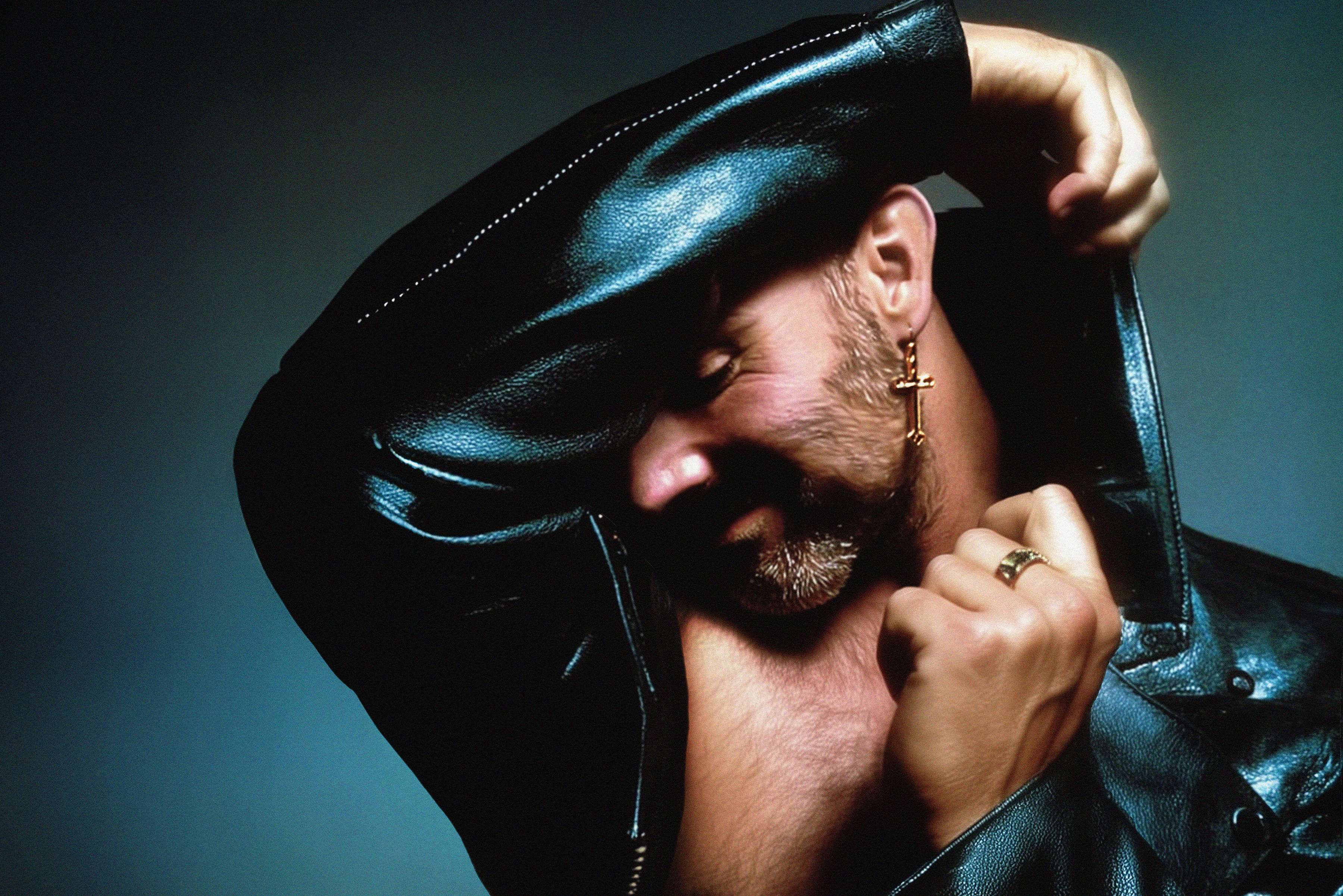

Image: courtesy David Hoekje

“Everyone’s asking how I’m dealing when all my friends are leaving town,” sings Olivia Rose, the lead singer of the dreamy alt-indie band Oh, Rose, on their new single, “Toilet Water.” “Am I going to stick around with them?”

The answer is yes and no. Rose lives in Olympia, Washington, the birthplace of her band and the place they released their first EP, That Do Now See, 10 years ago. Everyone else in her band now lives in Portland, where they recorded their newest album, Dorothy, this year. Dorothy, which came out on September 5, bounces between joy and grief, rage and gratitude, '80s synth-pop and shoegaze jangle. Rose’s voice can be breathy and ethereal, it can be hauntingly broken and sorrowful. “When I think about the album, it’s kind of this sonic quilt,” she says. “It has pop, it has grunge, it has folk elements, it bops all over the place.”

Her subject matter is just as amorphous, shifting from meditative, serene metaphor to an almost stream-of-consciousness processing of internal ruptures and past relationships, familial, romantic, or platonic. “I’ve got a lot of problems still,” she cries, again and again, in “Toilet Water,” until her bandmates join in her mantra. It’s an apology, an acknowledgment, an acceptance, a release. The grounding presence—in her music, her music videos, her life—are her friendships, specifically her bandmates. She’ll be down to visit them September 14 and 15 for shows at Revolution Hall, opening for other friends: the synth-pop band Future Islands.

Brooke Jackson-Glidden: You just hit the 10-year anniversary of your first EP. What is it like to revisit that initial set of songs, and to reflect on what Oh, Rose looks like now?

Olivia Rose: It feels really good. It’s kind of surreal that it’s been a decade. I’m proud that we’re still a band. The whole band is in Portland now, but the core group of people, we’re all still very close, despite the distance.

BJG: I feel like people who know your work can pick up on that, especially in your music videos. You all have fun together. I’m thinking specifically of the music video for “The Call." It’s basically all behind-the-scenes footage from your first tour with Future Islands, right?

OR: That’s a through line throughout our videos. From the first music video we did, “Prom,” there are similar people or characters recurring in all of our music videos. It’s a nice showcase of friendship.

BJG: That makes me think of your new album—I saw on your Instagram that you referred to it as an album about love. Listening through it, I see a lot of different manifestations of love, in terms of friendship, particularly.

OR: I definitely think it’s exploring a lot of themes of love, as far as friendship goes. For songs like “Back 2 U,” it’s about refinding love, maybe in past relationships. A lot of it is about the resilience of love, in friendship and family, in partnership as well. In a lot of our earlier work, albums like Seven (2015) and While My Father Sleeps (2019), we touched on themes of anger or grief. With this record, I was trying to really sit with the good: what I’m really grateful for. A lot of that comes down to love for my community, the resiliency of our friendship. And our partnerships! We’re all very close—with each other, with each other’s partners. It’s this potent community, and when I think about the album being a love album, I view it as this buoy of love and friendship that I was anchored to throughout some really large storms in my life.

Image: courtesy David Hoekje

BJG: The new album is called Dorothy, and it’s named for your grandmother. How does she show up in this album?

OR: Before even naming the album Dorothy, I knew I wanted to make a love album. So what does that mean, what is the embodiment of love for me? That’s my grandmother, this constant support figure in my life. My last album, While My Father Sleeps, was recorded after my mom passed away, and within a year, my grandmother Dorothy died. These two matriarchs in my life passed really close together, and I had really different relationships with both of them. My grandmother was an avid quilter. It feels like this embodiment of that: What am I stitching together with these songs that I’ve written, after these [earlier] albums that were so focused on anger and loss?

BJG: It’s interesting that you bring up anger. The song “25, Alive,” on your previous album has this repeated line, “I don’t want to feel anger anymore.” You grapple with the anger we feel in grief, and with wanting to separate yourself from rage and the complicated relationship that your mother had with it. But anger emerges in this new album in different ways. What does your relationship to anger look like now, in the album and in your life?

OR: The funny thing about anger is that it doesn’t go away. It’s a constant revisiting of it, reworking of it. The song “Dog” [on Dorothy] is very much about being called back to that space. I think maybe anger is rooted in love, feeling pulled back into that. That’s that through line from the other works. It’s still there. It’s been how long since I wrote “25, Alive”? “I don’t want to feel anger anymore,” but yeah, I still do, I still have a lot of problems, I’m still a human being. It’s a part of a story as well. It’s not something to get rid of. But how do I revisit that? You can come to the other side [of that anger] in understanding and gratitude, but there’s still going to be a dog. There’s a line [in “Dog”]: “I can’t seem to get out of collar.” I’ve done all this work, and then, boom, there’s that thing that’s showing up in this other area, and I’m just five years old and screaming.

BJG: That’s such a visceral image, and it feels true to the vulnerability of a lot of your work. How much are you actively processing as you write?

OR: It really depends on the song. With a song like “Dog,” that was one that just came falling out. I can apply different meanings to it. Maybe that’s the thing I need to examine during this period of my life. I feel most satisfied with a body of work when I can really step back and ask why all the songs were written. “25, Alive” was very much me processing; “Toilet Water” is very much like that. But “It Takes Time to Love Me,” [which has lyrics like “I don’t want to leave my house/I don’t want to leave my roommates/I don’t want to leave my bed”], I wrote that two or three years before COVID. It felt like this weird third sight: you’re creating a gift for yourself for the future. If you so choose to revisit it or open it, you can find different meanings. Sometimes it’s quite literal.

BJG: Now that so many of the members of Oh, Rose are down here, how do you retain that relationship? How do you all still collaborate?

OR: I’m a holdout! I just have to jump in my car and head down to Portland. I’ve thought a lot about moving to Portland, but I’ve also carved out this really beautiful, nice life for myself in Olympia. They all moved down in 2018, and in 2020 I carved out this sweet, quiet, nice life in Olympia. I can go to Portland for a couple days, get my social things in, work, and then I can retreat into this sanctuary. [Olympia] is a very supportive place for what I need right now in life. I love that it’s between Portland and Seattle. My brother lives in Seattle, so being in this in-between tiny town works for my lifestyle.

BJG: It’s almost like work-life balance. You’re leaving work down here when you go home.

OR: Oh, for sure.

BJG: You’ve always played shows down here, but I wonder how different it feels now that so much the band is here. What is your relationship to Portland’s music scene now?

OR: I still feel really involved in it. But also, like, not at all. I know the Portland music scene. My bandmates are so involved in the Portland music scene. I can tap into it when I want. But for the most part, people don’t really know me. There’s this air of mystique that I get to maintain. That’s that work-life balance. They know me through my work, and they know me through the people I’m closest to, but they don’t really know me.