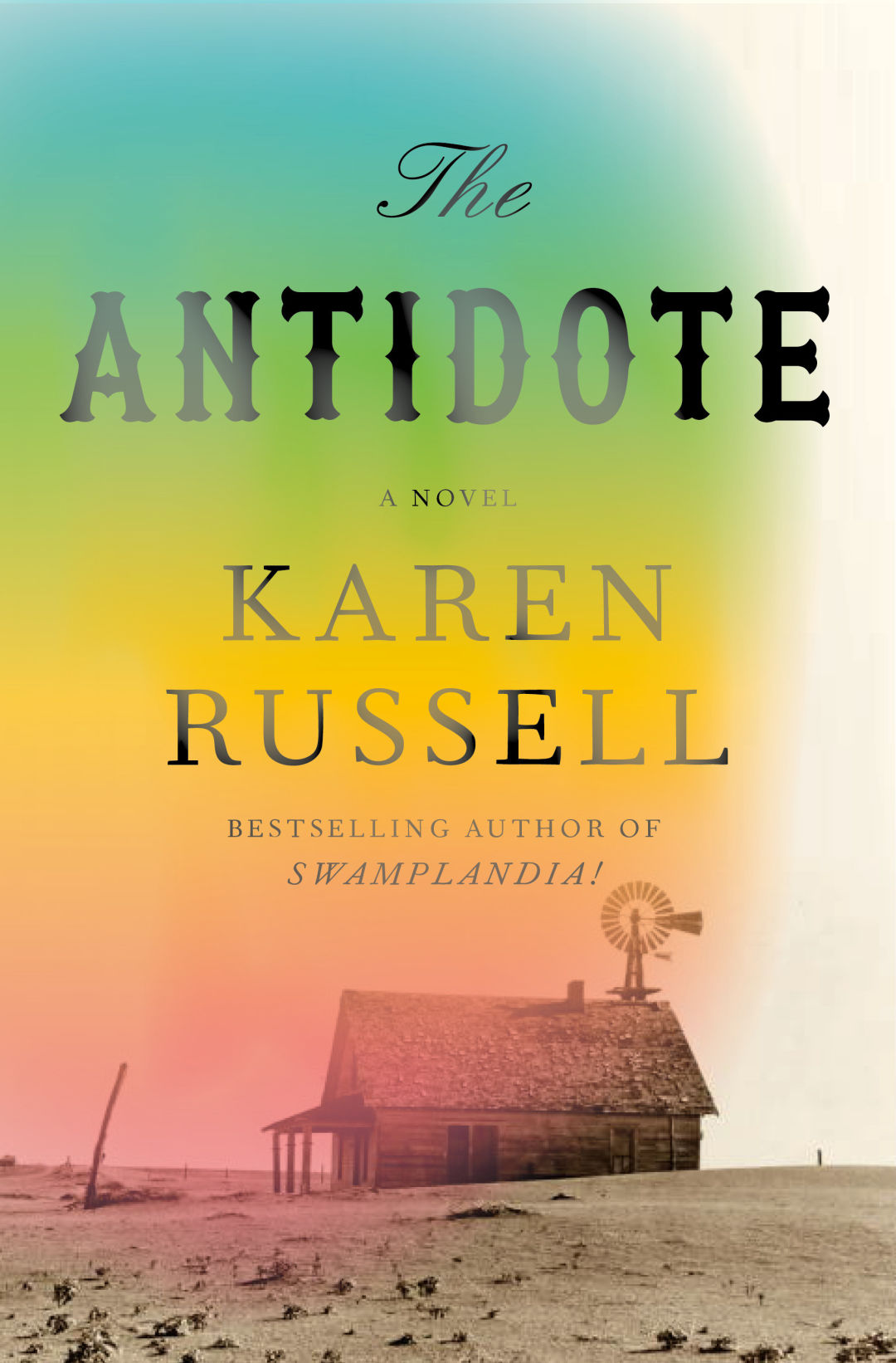

Karen Russell on Her Witchy Dust Bowl Epic, The Antidote

Early in Portlander Karen Russell’s latest novel, The Antidote, its titular witch is trying on names. Rather than cast spells, the Antidote’s powers as a so-called “prairie witch” are akin to an occult therapist’s. She is a vault, a bank in which forlorn souls can “deposit” memories—offloading their guilt and squirreling away nuts of happiness to be later withdrawn, if all goes according to plan. Needing a snappy moniker to sell her services, she spitballs one at another fledgling witch. “I like it,” says the other in her coven. “Makes a big, dumb promise.”

Over Zoom recently, Russell described her witch as “a traumatized woman selling her oblivion as a cure-all.” Before she becomes the Antidote, Antonina Teresa Rossi is an orphan and a teenage mother cast out of early 1900s puritanical society. She finds a calling and a curse in prairie witching. Clients confess their secrets into the Antidote’s polished hearing trumpet, and, in a dissociative fugue, she files them inside herself; she doesn’t know what her clients have deposited in her, and, unless they withdraw it, neither do they. Her name sharpens the point, with its ability to clip horrors from collective memory, but the Antidote is just one of Russell’s many characters backed into a destructive compromise to survive. It’s no coincidence that Russell’s setting, a fictional town called Uz, Nebraska, shares a name with Job’s homeland.

The book collects an ensemble cast’s testimonies in the first person—including from a cat, a scarecrow, a crooked sheriff, and several generations of a Polish immigrant family—as they navigate their own Biblical tests of will during the Dust Bowl. We get the most insight into the Oletsky family, three generations of Polish farmers who, fleeing German occupation, moved to Uz for the promise of free, loamy land, only to learn they’d been shipped across the world to colonize another marginalized population, Native Americans.

The novel opens in the apex of the ecological disaster, Black Sunday. In the spring of 1935, one of the worst dust storms on record threw an estimated 300,000 tons of desiccated topsoil across the Midwest, burying houses, cars, and people. The book ends a little over a month later, when 24 inches of rain fell on the drought-suffocated region in 24 hours, flooding the Republican River and drowning so much scorched earth: an extinguishing fix, a deathly antidote. The social dynamics these conditions create, however, are the meat of the story—though it’s often hard to separate one from the other. Here’s a young Antonina precociously meditating on the world’s machinations:

To be pursued by a cloud is a terrifying experience, like trying to outrun a forest fire, a predator that could not see or hear or smell me, that would consume me without realizing it. Hunger without a body to contain it. Hunger nourishing itself with anything in its path, trees and dams and sheds and silos and entire barns.

This cloud could be a storm, but it could also be industrialized society, blind bigotry, capitalism, neoliberalism, any market-driven society, any dogma, any mob or militia. In their shadow, we grasp to a false hope that someone, some authority figure, is controlling the next move, some entity compelled by reason or motive or vengeance instead of a simple formula. How often do we blame “the algorithm” today?

Image: Courtesy Annette Hornischer

The witchcraft of it all carries the sharp and winsome magical realist style that made Russell famous in 2011, when her debut novel Swamplandia! was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. That book followed a family of Floridian alligator wrestlers navigating various depths of hell. A calamitous family drama undergirds spiritual allegory as its young heroine mourns her mother and the family business that dissolved without her.

Russell has published a couple short story collections and a novella since, but until The Antidote, none of her stories—which she talks about as if they’re conjured from outside herself—has grown to book length.

“I got the idea for this book a really long time ago, and then I just didn’t know how to write it,” Russell says, comparing her original vision to Howard Hughes’s not-quite-flying boat, the Spruce Goose (“literally overburdened with his ambitions”). Getting it off the ground, she says, involved a lot of learning and unlearning. Specifically, expanding upon the winner’s history of the Great Depression Steinbeck and textbooks had offered her as a kid.

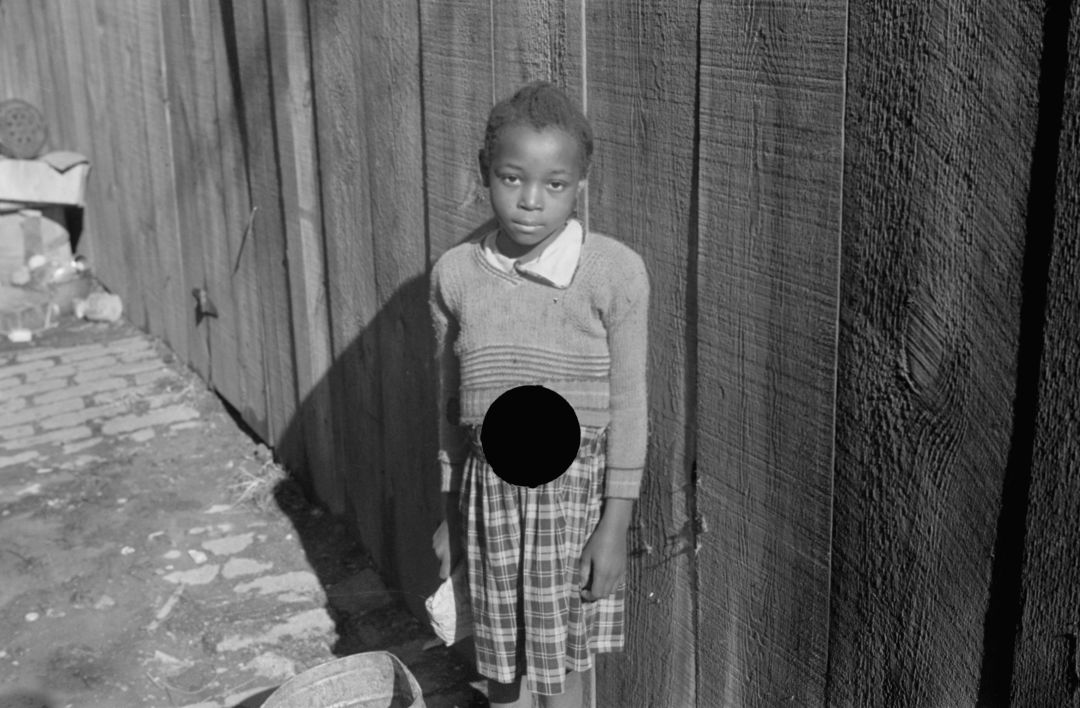

Digging through photographs from the period in the Library of Congress helped broaden her understanding. One of Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, the Resettlement Administration (RA), sent photographers into the Plains with a checklist of images to collect as a means to “show America to Americans.” They wanted churches “on Sunday,” “[c]hildren at play (dogs),” images of stores, “people buying”—certainly not of Black people, Native Americans, or any racially integrated social gatherings. The story was written before it was reported. And the agency head, Roy Stryker, worked as propaganda photo editor. He placed the images that aligned with FDR’s policies in government publications and news outlets, and he destroyed the images that told other stories, famously by punching holes into the negatives. In recent years, the Library of Congress made this archive of censored images public.

Russell put several of these hole-punched images directly in her book, setting the photos next her prose, and wrote one character as an RA photographer. It’s hard to articulate how unsettling these images are—lives and circumstances so flagrantly deemed unworthy of representing America. Russell puts Stryker’s historical edits, what she calls “crimes of memory,” in conversation with the Antidote’s edits, and the photos become a “shadow archive” standing in for and amending public memory.

There was at least one Black RA photographer, Gordon Parks, and several women were involved in the project, most famously Dorothea Lange. But the book’s RA photographer, a young Black woman named Cleo Allfrey loosely based on those two photographers, is certainly a fiction. Allfrey is aware of and frustrated by her role in creating Americana propaganda, but tries to be complicit, at least for a time. Then she stumbles upon a camera that takes pictures outside of time. In the darkroom, scenes of the past and future develop, projecting past joys and possible outcomes, as well as casting futures foreclosed by the greed of short-sighted overfarming, bigotry, and colonialism.

Similar to retroactively pulling the photos from the RA cutting room floor, Allfrey’s supernaturally captured images stand for a kind of impossible truth in the face of so many bent realities. The people in them, Russell mentions several times in the book, don’t seem to know they’re being observed. And Allfrey, never sure of what the darkroom will give her, is in no position to doctor the images either.

The book is packed with examples of people telling what they seem to believe are good-natured white lies. “I invent these vaults, these prairie witches,” Russell says, “but I think a lot of us do this in house,” when we’re backed into a corner, unsure “what to do with harms done and harms endured.” When the Antidote’s proverbial vault is robbed, she plots a way around admitting she’s lost the town’s stowed memories. Even the corrupt sheriff, in his own sadistic way, seems to believe his fabricated convictions will create peace in Uz. Again and again Russell returns to how dubious it is to play God. Ironically, her book is doing something similar.

“There is a funny tension in trying to write a weird ass book about this real history,” Russell admits. She offers a favorite Flannery O’Connor quote: “The truth is not distorted here, but a distortion is used to get at truth.” In the book, she gives Allfrey a similar line to defend the photographer Arthur Rothstein’s iconic photo Father and Sons in a Dust Storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma. In it, a father and his sons run toward a shed half submerged in a snowbank of dust and appear to be fleeing a storm. It’s a truly affecting picture, and one of the most famous of the era. The problem is, you can’t see anything in an active dust storm. Instead, Allfrey suggests, “He’d rearranged reality to reveal a truth that would be otherwise unknown.” But her boss, Stryker, isn’t having it. Despite a projected rigor for truth, questioning the impossible image that confirms his and the country’s narrative was blasphemous. Remember when it was taboo to say the government lied?

Karen Russell will read from The Antidote at 7pm on Tuesday, March 11 at Powell’s City of Books.