Wine Snobs, Moody Bastards, and Game Hens: Inside the Vat and Tonsure

Instead of greeting diners with a “hello,” the staff barked “no hens” or “half a hen”—the number of the Vat’s celebrated roasted birds the kitchen had on hand.

As the story goes, Michael and Rose-Marie Quinn met as coworkers at the United Nations in Vienna then moved to Portland. In 1978 the couple set out to re-create what they loved about Europe: great Bordeaux, opera music played at Led Zeppelin levels, and simple food. They called it The Vat and Tonsure.

He was the quintessential publican, always parked at the bar’s end, drinking, and chatting up customers. She hid in the kitchen, cooking a menu of six entrées, three of which were usually not available. Rumors persisted they were spies. According to James McQuillen (one of the Vat’s infamous waiters, a coterie of wine snobs and moody bastards who loved to riff on existentialism before taking your order), “they did nothing to suppress the glamorous veneer associated with that.” The place even had its own language: instead of greeting diners with a “hello,” the staff barked “no hens” or “half a hen”—the number of the Vat’s celebrated roasted birds the kitchen had on hand.

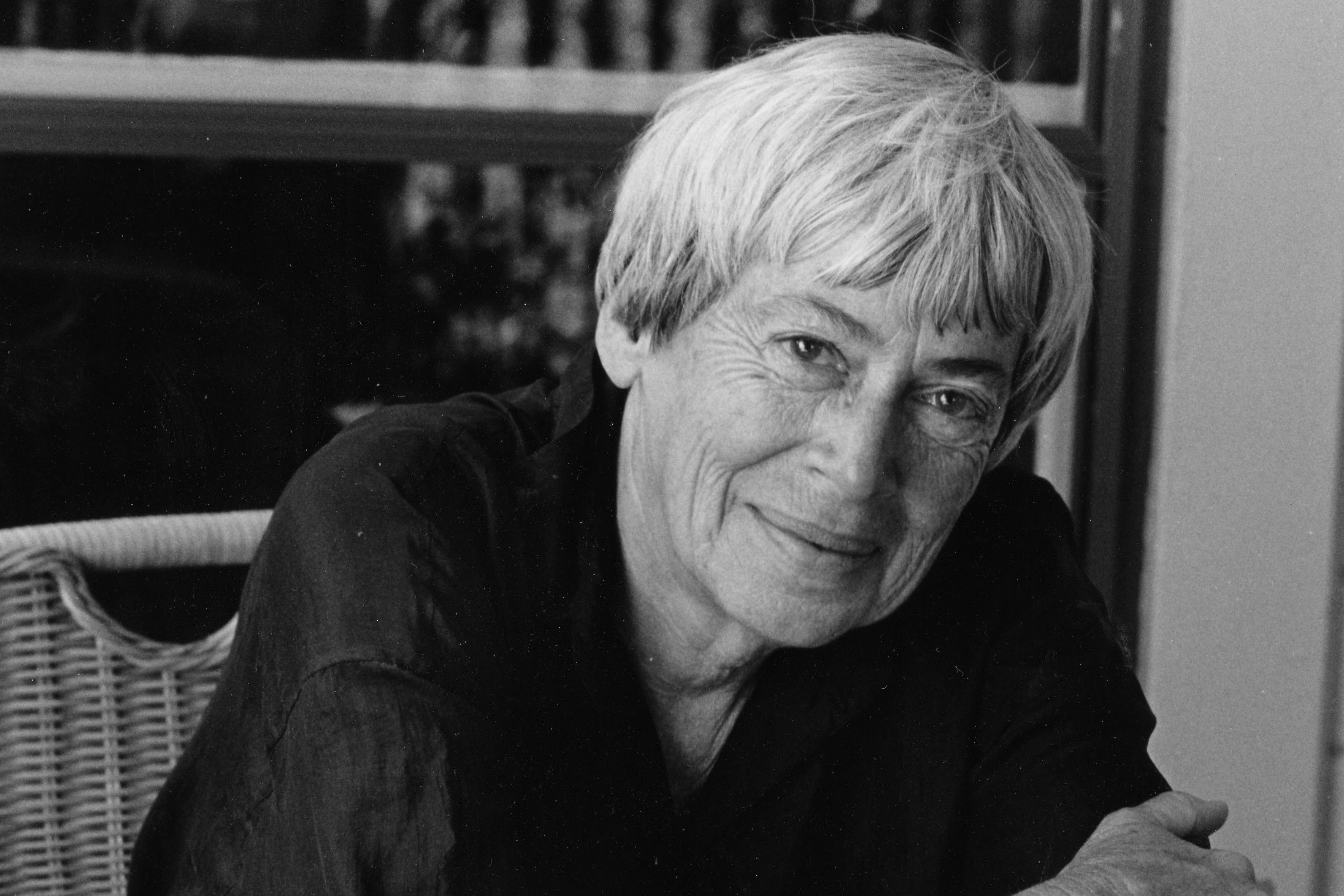

A crucial era of Portland cultural history unfolded at the Vat’s creaky, stained plywood booths: Gus Van Sant, mayor Bud Clark, Oregon Symphony musicians, Ursula K. Le Guin, film critics and oddballs and art gallery owners—all basked in the Vat’s otherness. As I noted in a 2003 Oregonian story: “Where else could you sit for hours on end debating the decline of poetry, or why everybody in Europe still hates us?” Says McQuillen, who went on to become a classical music critic, “Together, Mike and Rose-Marie made a place like no place I’ve ever been. It was very echt Portland in a way that longer exists.”

For 19 years, before it was shuttered to make room for the Fox Tower, the Vat showed that restaurants could be like crazy living rooms (if your living room housed a great wine cellar and moody existentialists).

Descendants: Expatriate (for cosmophilia) or Janis Martin’s Tanuki (for unrepentant attitude with your omakase and splatter flicks)

Confessions of a Vat Rat

Portland film critic Doug Holm on the hens, the room, and the infamous waiters of his 1990s haunt The Vat and Tonsure.

As told to Karen Brooks…

The scene: “The place looked inviting from the outside, the cozy wooden furnishings, the windows with the red curtains and the small lamps with red shades. It was especially nice in fall or winter; late on a winter night when the streets were bare and snow might start to fall. Walking in was to a blast of warmth and high volume chatter. I never went into the loft upstairs. It scared me. Always felt like it was going to fall down."

The hens: "They only made so many hens [each night], so you had to get there early. Once, I watched them prepare the hens. They put about a box of salt in each one (perhaps to make the customers thirsty?). The big joke of the place was that the crème brûlée was always crossed out on the menu. Actually, it hadn’t been served for a decade, since 1989, but kept appearing in food reviews forever after."

The help: "The waiters were wine connoisseurs in public and private life, and mostly surly—especially Jeff, who just didn’t like people, and in a sense, who can blame him? Bill was the lady killer of the bunch … Women just automatically loved him, and flocks of girls went to the bar to sit there alone and read and hope to talk to him. Bill got all the ladies that Jeff wanted, because Jeff looked like Roger Ebert. Jeff was famously the most mean of the waiters, in that customers were required to know their stuff about wine. James, the shortest one, was a nice guy (see “Confessions of a Vat Waiter,” below). Ben just prattled on and on—it was thanks to Ben that I became first aware of the “Portland Farewell,” i.e., people saying goodbye for a good 15 to 45 minutes before actually getting out the door. Also there was Chuck, a math genius and master ship builder. Doug was a raging alcoholic James Joyce fan who gave up booze, married this nice girl, changed his name and moved to Boston.

Jeff lives around the corner from me now. He’s very nice and friendly these days."

Confessions of a Vat Waiter

James McQuillen, the “nice guy” of the Vat waiter coterie, sets the record straight on its infamous wait staff. McQuillen, who worked the Vat floor 1994-1997, is a classical music critic for the Oregonian.

As told to Karen Brooks…

The Vat vibe: “There was no sign outside. By the time I arrived, the Vat had a self-selecting clientele... People were still smoking. You couldn’t escape the smoke. People who weren’t used to it would get bent out of shape. They’d also get bent about the inflexibility of the volume of the music. Customers would often ask, ‘Can you turn it down?’ The answer was no. Owners Mike and Rose-Marie were into classical music; Rose-Marie was a singer, and opera was No. 1 on the stereo system. Celtic musicians Kevin Burke and Jonny Cunningham—among the absolute top fiddlers of their time—would come in with fellow musicians, hang out, and order ordered bottle after bottle of Veuve Cliquot. They often had instruments with them, and on a busy Friday night, the stereo would go off and the music came on, lasting into the night.”

The funky split-level space: “(Architecture writer) Randy Gragg had a good observations ages ago, that the Vat was an ingenious collection of different spaces. The bar was convivial, a meeting-up place. The mezzanine had intimate booths; the booth furthest from staircase was famed for being very intimate—as in, yes, people were known to have sex there. The tables upstairs were quiet, removed from hustle and bustle. The space incorporated distinct experiences.”

The famed wait staff: “When I worked there, the majority of waiters were Reedies, myself included. I wasn’t necessarily the nice guy, but one of the nicer guys. A customer once told my co-worker Andy Gaudreau: ‘You’re being too nice; this is disorienting.’ But I think it’s important to demythologize the rudeness; it was more like European-style professional distance.

The only staff was Rosemary, Mike and the waiters, who also helped in the kitchen. On busy weekend nights, it could be insane, which contributed to how we interacted with people: no time, no BS environment. When the place was full, it was probably 75 people. Three people working, so we flew. We loved to throw on the Barber of Seville and just crank it … It was totally energetic ... We didn’t have a mechanical dishwasher. Everything was done by hand. When it was all done, we washed, cleaned up, drank wine, and played chess.

Have you seen the Battered Bastards of Baseball, about the Portland Mavericks? They embodied a certain spirit of Portland, a genuine kind of misfit, and the city loved them. If you want to get the [Vat] vibe, watch that movie, it’s a blast. Vat waiters tended to be a bunch of smart guys (always guys, Rose-Marie refused to hire women). They didn’t want to have corporate jobs or to be lawyers. They loved being in this convivial atmosphere; they gave it an intellectual charge. On off hours, they were reading, writing, doing photography. In a way, they were the restaurant industry analog of the Mavericks—an oddball group of guys, Portland, indie, sometimes totally nuts."