5 Days That Shook the Portland Food World

Yonder chef Maya Lovelace

Early Wednesday evening, July 1, a text circulated around Portland food circles. A local chef was being called a rapist “in the spirit of calling people out on their shit during this revolution... Boycott this restaurant and tell your friends. This is verified. Please support the survivors & repost.”

The claim, made by an anonymous person, was reposted in big type on the Instagram account of Maya Lovelace, a prolific social media presence and the chef-owner of fried chicken haven Yonder. “Hell yeah,” wrote Lovelace. “This is true and so many folks have known it for years and have done absolutely nothing about it. Also do y’all remember when he had his brother rig the results for the @eaterpdx chef of the year using bot voters? Lmao that was craaaaazy.”

It's not clear how this charge was verified. No public sexual assault charges have been filed. But some of the chef’s former employees quickly contacted Lovelace, detailing unwanted advances. One claimed he “packed a gun” under his chef’s jacket.

Lovelace offered to post their stories, anonymously, to protect any professional retaliation. The reaction surprised her. “People just wanted to share,” she tells me. “They said it was a relief to talk about it.” With that, she put out a call to anyone to air local industry misdeeds to her 7,000 Instagram followers, calling it a movement. The rules: no denying or refuting stories; apologies and accountability welcomed.

Within days, kitchen cultures from prominent Portland restaurants were under fire. Claims ran from misogyny to wage theft to sexual harassment. Big or small, most said concerns were unheeded by tuned-out management. Among the names that surfaced: Higgins’, Olympia Provisions, Farm Spirit, and Submarine Hospitality (Ava Gene’s, Tusk, the Hoxton). Some owners issued quick mea culpas and promises to do better with the culture of their establishments. Others shared back-channel emails, questioning the absence of fact-checking or vetting sources.

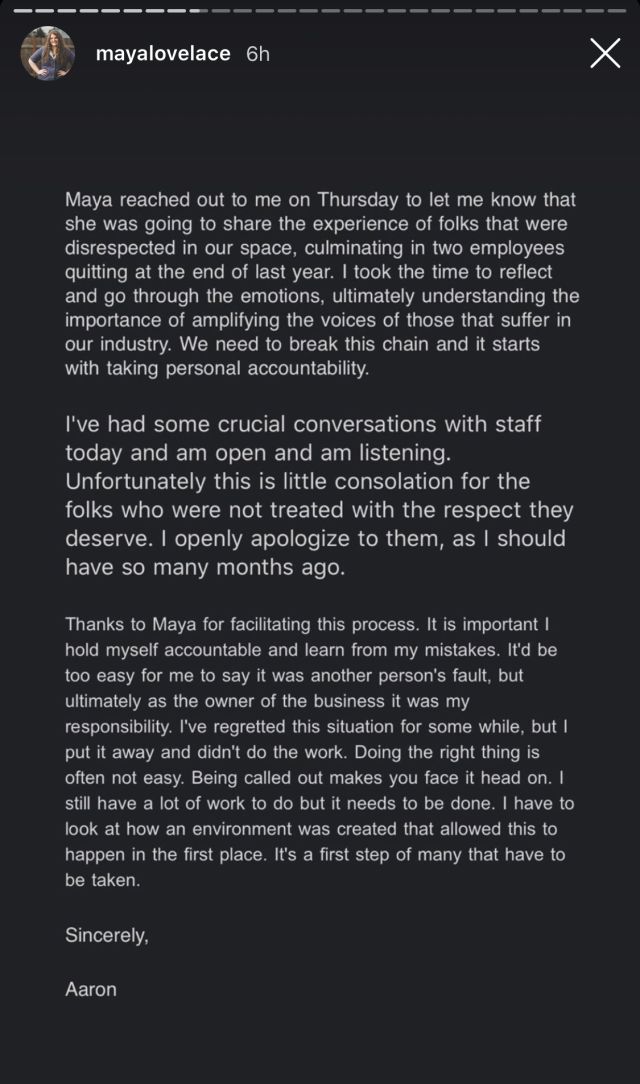

Screenshot of Aaron Adams's response from Maya Lovelace's Instagram story.

All this, following the online meltdown of chef John Gorham and the fall of his restaurant empire. Was Portland’s food scene imploding?

Lovelace, 32, does not shy away from confrontations on her social media platforms. As she tells it, her recent Instagram experiment started, in part, after sparring with blogger and Mi Mero Mole owner Nick Zukin, whose online spats are legendary. It wasn’t the first time they tangled. “Nick,” she recalls, “started researching my (North Carolina) family to see if anyone owned slaves. He accused me of cultural appropriation. I’m here to have any conversation on Southern food.”

The two tangled again in the past week after a Zukin post that seemed to equate his business struggles during the pandemic with the way George Floyd was murdered, drawing swift denouncements. “It just pissed me off, to be frank,” says Lovelace. “Then, I was on my Instagram account and saw someone had posted about [the chef rape charge]. I’d been aware of these allegations. Portland has a whisper network, what cooks and bartenders talk about after hours. After years of trying to push the story, I was over it.”

Lovelace decided then and there: a reckoning in Portland was due, out in the open. “I didn’t expect anywhere near the volume of responses,” she says. “What I posted was a tiny fraction of what I received. A lot of these complaints are not about owners. But if the owners, if the culture is not aware of it, it’s a really dangerous place to be.”

Problems in the food industry are not new: the long hours, high anxiety, and mental health issues simmering inside macho cultures jacked on adrenaline and pressure-cooker situations likened to battlefield situations. Before COVID-19 devastated the industry, conversations around #MeToo harassment, pay inequality, and calls for healthier cultures dominated food news stories. By Saturday, July 4, Lovelace’s platform for “the silenced” had exploded. The day began with a former employee leveling a claim that celebrity chef Gregory Gourdet, who is Haitian-American, had run “the most toxic kitchen in Portland” and had stolen dessert recipes. It was a turning point.

By Sunday morning, emotions were high. Gourdet was devastated to see the accusations, which he says first surfaced in May on a former cook’s Facebook page. He says he was taken by surprise and immediately reached out to the woman several times in May, to no avail. “Everyone’s experience will be their truth. But it’s not fair to go on social media and attack me when I made myself available and did not get a response,” said Gourdet over the phone.

Gourdet has been outspoken about industry problems, including in a recent Portland Monthly interview. “But this is all over the place,” he says. “Those claims about [a rape] shouldn’t be on the same platform as someone who doesn’t feel paid enough. Now it’s out there for everyone to have an opinion, but there’s no system for resolution.”

He says he explained this to Lovelace, whom he once considered a friend. “She sent me heart emojis and tried to apologize afterwards, saying, ‘I know this sucks.’ I said, ‘I can’t accept your apology because you know exactly what this, in this medium, does to people.’”

Adds Gourdet: “We’re all so vulnerable right now. We’re listening to each other. The system is broken. Yes, these conversations are needed. It’s time to reflect on what kind of a leader I was. At the same time, I would have listened just as closely if not drug out into a public platform.”

Among those posting apologies on Lovelace’s Instagram: Cuban-American chef-restaurateur Aaron Adams, known for his punk-rock ethos. Over the phone, Adams wept as he tried to trace how communication went so south at his acclaimed hard-core vegan spot Farm Spirit. “I fucking failed. I have values and didn’t live by them. I didn’t listen to people when they complained. It’s easier to listen to management than employees; it’s easy to have your own views validated. I was acting like an executive chef, lifting weights at the fucking gym. You can’t look away from your business.”

Aaron says he gathered his staff in his backyard on July 4 for hard, open conversations. “There was lots of crying, especially me,” Adams says. “I have leg cramps I’ve cried so much.” Aaron says the accusation that he called a chef stupid was true. “He didn’t put a celery root purée dish on the right plate. The pressure to be perfect is so enormous. I’m thinking of closing Farm Spirit. I don’t care about doing fine dining ever again.”

At first, Adams was angry at Lovelace, but now he’s grateful. “I feel great sense of relief,” he says. “Once a chef put a knife in a fryer and stuck it on the back of my neck. We think we’re so good because we’re not that. It’s easy to think, ‘I’m so woke, doing such a good job.’ Well, maybe not. One thing I’ve learned: I will never look away again.”

After criticisms about Ava Gene’s culture appeared on Lovelace’s site, co-owner Joshua McFadden, a nationally known chef and cookbook author, took to his Instagram account to issue what employees saw as a canned nonapology on a colorfully designed background. Judging by the comments, McFadden had lost the room, including a stinging rebuke from chef Sam Smith, his partner at the restaurant Tusk, who posted: “Your lack of accountability is disappointing. The people that have been struggling under your leadership deserve more. We obviously all have work to do, but you need to do better than this.” Former Ava Gene’s sommelier Dana Frank, owner of the acclaimed Bar Norman, also weighed in, suggesting to McFadden, “Put as much effort into your apology as you do hand lotions and vibes.”

Sunday evening, five days after it began, Lovelace removed the posts, putting the project on hold. “Hi everyone,” her note began. “What started as an offer to use my privilege and platform to magnify marginalized and silenced folks in the PDX food scene has grown exponentially out of my control. In the past few days, I’ve hurt people I care about deeply, helped folks speak their truth for the time and felt useful in a way I didn’t anticipate.”

Lovelace called the experience difficult and miserable. “First, I received a long, anonymous attack from a secure Swiss email server that said I was about to be served with a libel suit … and also ‘watch your mouth.’ Strangers called me a piece of shit and a hypocrite. Some people said they’d never come to my restaurant again. I signed up for a certain amount of hate. I’m posting from people often silenced. I expected a little bit of it.”

Even without Lovelace’s running post, the story is still unfolding.

“Everyone is struggling how to respond,” said Kurt Huffman, owner of Portland’s ChefStable restaurant group. “It’s easy to feel betrayal by another industry person. We know we’re not perfect. How each person responds will be telling—how they listen, how they are held accountable. I know we’re going to be very proactive, reaching out to our employees and letting them give us feedback anonymously.”

By late Sunday evening, Gourdet finally connected with the cook who spoke out against him. In a follow-up email, she told me the conversation went well. “He told me he wanted to give me the platform to express myself. I asked if other people could share their stories with him. He was receptive.”

What was her for her takeaway on this whole experiment? “It’s complicated,” she tells me. “The service industry is very flawed. It can feel overwhelming to try to tackle issues. Most cooks feel pretty anonymous in the Portland food scene. When someone like Maya uses her platform to empower people, it feels like people would actually hear it. It probably wasn’t the most graceful way. It got really messy. But it got the conversation started.”