Malka, the Wonderfully Imaginative House-Turned-Restaurant on SE Division Street, Will Close

Malka, known for its whimsical food and interior, will close February 26.

Image: Michael Novak

Malka, one of the biggest shining star restaurants to open in Portland in the past few years, announced on January 16 that it will permanently close on February 26.

“The overriding reason we need to close is financial,” chef and co-owner Jessie Aron wrote in an Instagram post. “While our newer prix fixe menu is significantly better for us and more profitable than the takeout model which got us through the first two years of the pandemic, we are still not making enough money to comfortably take care of the needs, health, and necessary rest for all who work here, ourselves included.”

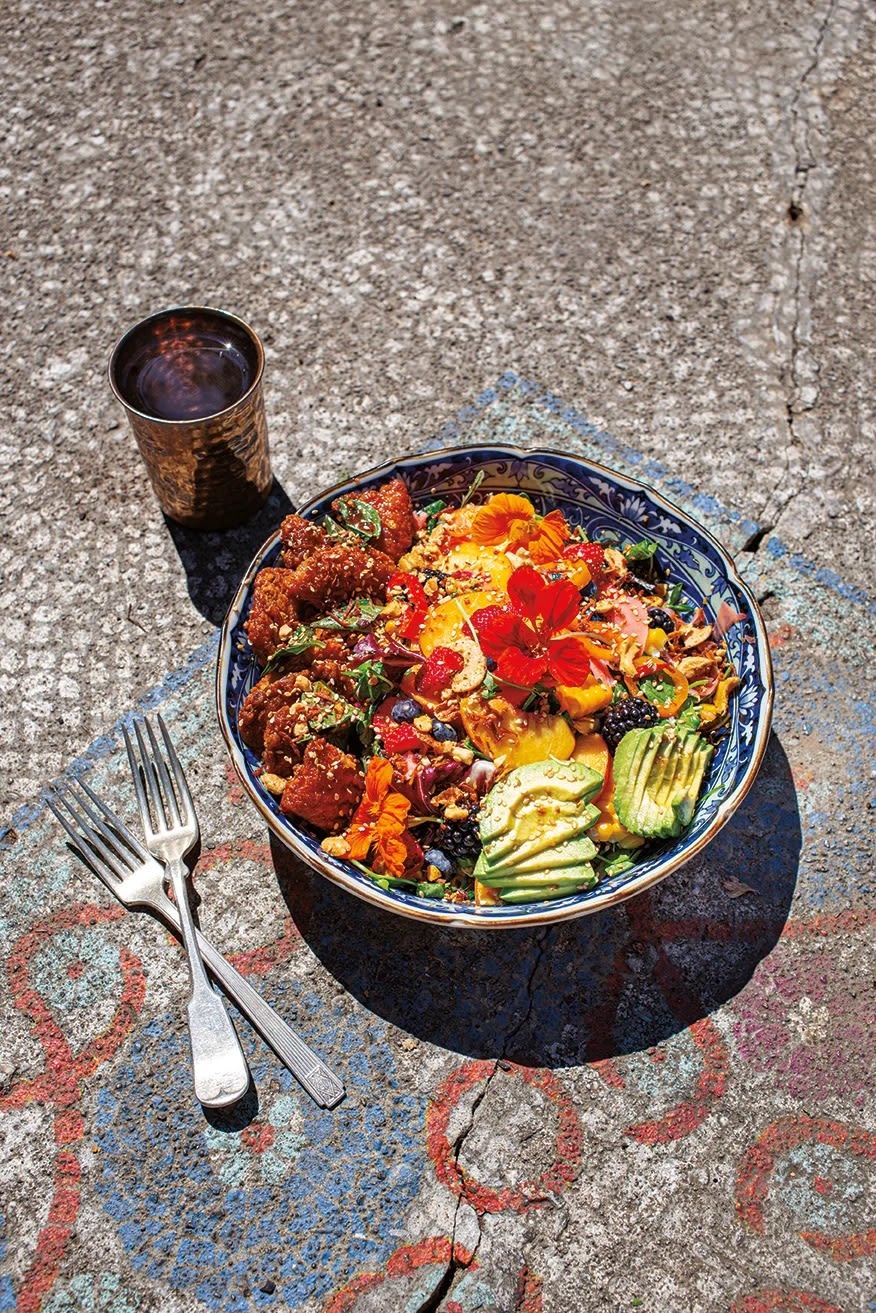

Named one of Portland Monthly’s Best Restaurants in 2020, Malka was heralded for its chaotic, otherworldly dishes that might combine five sauces, a garden’s worth of different herbs, and anything from kiwis to blueberries to puffed jasmine rice, and boasting names like An Important Helmet for Outer Space or I Have a Lot of Feelings. Even side dishes like artichokes required a considerable grocery list. Aron’s cooking style was unlike any other chef in town, making dishes that were like something you might eat in a fairy tale inside a fantastical, colorful restaurant space: full of crunch and acidity and textures and flavors, blending influences from Italy to Thailand to Vietnam to Portland.

The Bellflower crispy rice salad from Malka, the number of ingredients for which may have topped 100.

Image: Michael Novak

But Malka was also frequently mentioned as an example of what timing and a pandemic can do to a fledgling business. Malka opened in late January 2020, five years after Aron, who had owned the Carte Blanche food cart, secured the house on Division Street that she transformed into a restaurant after raising funds for renovations and dealing with permitting red tape. Six weeks later, Malka had to shut down its dine-in service due to the pandemic. When it reopened for takeout, it was one of the hottest places to pick up a pandemic comfort meal, and the phone was ringing off the hook. But even after two years of bustling takeout business, Aron says the restaurant often lost money doing takeout.

“It wasn’t a good battle for us, especially as food costs kept rising. We felt like we couldn’t charge more than $20 for takeout in a cardboard box, but we weren’t making ends meet,” says Aron. Adding to the challenge: the fact that Malka’s dishes required so much prep and so many ingredients. “The food here is not practical, and I think that’s part of why people like it so much.… But it’s not like pizza, which is delicious and makes sense from a fiscal standpoint.”

During the summer of 2022, Malka reopened for indoor dining for the first time since March 2020 with a $60 prix fixe menu, which included three courses and 20 percent gratuity. It was more profitable than takeout, Aron admits, though the restaurant received some pushback from customers who regularly ordered a dish or two for takeout but didn’t want to commit to a $60 meal. That pushback prevented the restaurant from raising its prix fixe prices even as the cost of food surged. A weeklong closure due to a wave of coronavirus cases among the staff also dealt a major blow: $5,000 of ingredients that were ordered for that week’s service were donated instead, and the restaurant couldn’t afford to pay staff during that week.

Over the three years since Malka opened, Aron and the other co-owners were going into debt—and also, Aron says, sacrificing their free time and personal well-being. With such complex dishes, the staff spent spending hours and hours prepping. “I’m sitting talking to you in my prep kitchen right now, and I have a pot of curry on the stove, I have 50 pounds of beef that needs to get braised, and I have potatoes that I almost forgot to take out of the oven before you called. There are four people just chopping away,” she says. “People are really fond of saying that the experience at Malka, and at so many restaurants, is magic. And there’s a joy people feel in feeling like we’re magicians. But we’re not magicians. We’re just people who are working really, really hard. It’s not magic. It’s just labor.”

It's no secret that the restaurant industry is a tough one, but the fatigue of trying to recover from the pandemic while facing rising costs makes it especially challenging now. Aron, who often worked up to 100 hours per week at the restaurant, says her hair has been falling out. Meanwhile, her partner in business and life, Chris Glaab, was juggling a separate full-time job while handling payroll, shopping, and helping with dishwashing at Malka.

Aron says it’s unlikely she’ll cook professionally again—”I’m trying to find a job that’s a lot less pressure,” she says—while Malka chef de cuisine and co-owner Colin McArthur is considering working in farming while potentially keeping a kitchen job.

Since Aron’s announcement, reservations for Malka’s remaining dinner services have completely filled up on Resy. And though Malka didn’t work out the way she’d hoped, Aron says she’s proud of everything that went into it.

“I’m thankful to everybody, and I’m sad for sure,” she says. “It was too much for me, I admit, but I’m really going to miss the people who work here and the sweet customers and the house itself. But rather than having too much shame or a sense of failure, the letting go of a job well done is the main reason this is all very painful.”