Why Are Oregon Therapists Training for 500 Fewer Hours?

Image: net vector/shutterstock.com

I want my therapist to be qualified. You know, armed with a dozen therapeutic modalities, fluent in psychology, and packing enough empathy to power a light show at a rave. So I was alarmed to see that, this year, Oregon dropped its client training requirement for licensed therapists down to 1,900 hours, meaning that new therapists in the state will now begin practicing with 500 fewer hours under their belts.

The state’s mental health statistics are abysmal: advocacy nonprofit Mental Health in America ranks Oregon 48 out of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, based on prevalence of mental illness and access to care. Shouldn’t we want highly trained therapists helping these patients?

“We talked about this quite a bit at the Oregon Counseling Association,” says former OCA president Jeffrey Christensen, codirector of the professional mental health counseling program at Lewis & Clark College. “But these hour changes don’t really reduce the time frame for folks to get licensed—it’s still five to six years of training. Oregon had much higher client hour requirements compared to other states.” Idaho requires just 400 direct client hours—basically a hobby. Washington requires 1,200 hours.

Oregon, population 4.2 million, has just 5,723 full-time-equivalent licensed practicing mental health professionals who work with patients. (That includes 498 psychiatrists, 836 psychologists, 362 mental health nurse practitioners, 1,884 licensed clinical social workers, and 1,596 licensed counselors and family therapists, according to a 2022 report for the Oregon Health Authority.) Good luck if you’re searching for a licensed therapist in Portland, especially a kids’ therapist. You call around, and receive the same replies: “I’m sorry, but my practice is full. Have you tried Sarah Therapist?” Sarah Therapist’s practice has been full since 2015, so maybe she suggests a colleague who has availability, but only weekdays between 9 and 11 a.m. Finding someone who accepts your health insurance, has relevant expertise, and has availability that doesn’t crash your school and work schedules feels more like winning the lottery than accessing health care. And this is the norm. In the same report by Mental Health in America, Oregon ranked dead last for youth mental health and care, with 1 in 5 kids between the ages of 12 and 17 experiencing severe depression, the majority not receiving behavioral care.

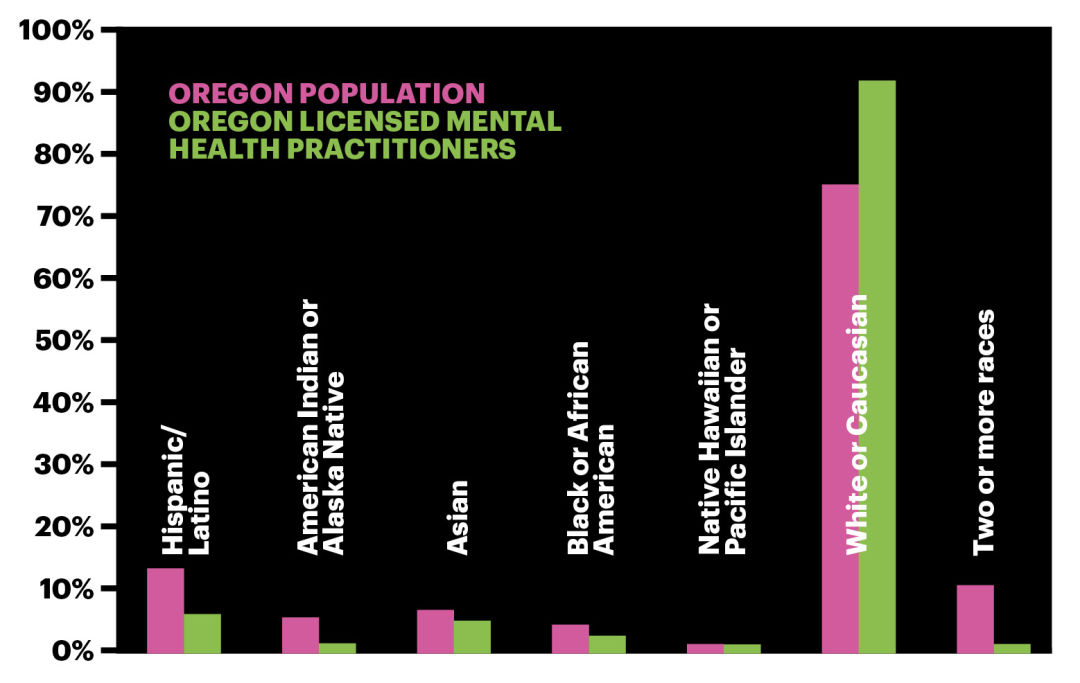

If that seems tough, finding an available BIPOC therapist can feel like not just winning the lottery but hitting the Powerball, too. Just 7 percent of Oregon therapists are BIPOC, compared to 25 percent of Oregonians overall, according to a December 2022 study commissioned by the Oregon Board of Licensed Professional Counselors and Therapists.

“It was really a large BIPOC-led coalition that was advocating for all these [hour] changes,” says Portland-area therapist Anjabeen Ashraf, who helped write the new legislation. “What’s good for the least of us is good for all of us. If we reduce the barriers to entry, it’s not only going to benefit BIPOC folks but also, say, rural communities, which are severely underserved in Oregon.”

Source: Oregon Mental Health Regulatory Agency Diversity Study 2022

Now therapists in training can complete 400 client hours during their two-to three-and-a-half-year graduate degree programs, which typically cost $60,000–80,000 total. That leaves 1,500 hours to be completed afterward, for which they’re paid around $20 per hour. Therapists typically see only 20–25 patients regularly, leaving time for paperwork, preparation, and, you know, sanity. That math pressures middle-class budgets into hemorrhage. “You can only hustle for so long,” says Ashraf.

Pretty much everyone involved in the profession is enthusiastic about the hours reduction—except, perhaps, the trainees who recently completed their 2,400 hours. “You have to realize that these individuals already had two to three years of education, and receive continuous supervision and oversight while getting licensed,” says Greg Peterson, the current OCA president. “Historically there’s a lot of burnout in counselors, within five years. People sometimes leave the profession.”

The whims of Oregon training requirements may become moot as license portability between states moves toward reality. Thirty states have now joined the Counseling Compact of the American Counseling Association, which will eventually oversee cross-state therapist licensing. Oregon hasn’t signed on—yet.