6 Design Stars Shaping Portland’s Craft Scene

LILITH ROCKETT: Lilith Rockett Ceramics

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Lilith Rockett’s vessels appear flawless. Clean, nearly translucent lines sweep and taper with an effortless, fluid energy. Look closer, and irregularities emerge. “For me, things get too static when they’re just ... perfect,” says Rockett, a self-taught studio potter. “I like to see it breathe—I like there to be life in it, I like it to undulate a bit. It keeps the energy going after your hands and the material are gone.”

Rockett’s career in pottery began with a fortuitous firing workshop in Los Angeles, where she’d been working as a camera assistant. She was hooked. After a stint at the renowned Xiem Clay Center in Pasadena, she opened her own ceramic gallery in LA’s Chinatown in 2005, representing herself and 10 others. “I jumped in with both feet in the deep end,” she laughs, “which is kind of how I do things.” In 2008, she and her family migrated north, seeking a simpler life in Portland.

Rockett stands apart from local production pottery studios like Pigeon Toe and Mazama: she throws all of her work herself at the potter’s wheel. And though her wholesale line can be found at local shops like Beam & Anchor, she still prefers producing original series for galleries and custom clients. She lights up when describing a fertile collaboration with New York star chef Matt Lightner (formerly of Portland’s Castagna), whose Atera restaurant serves its artful modernist creations on her custom dishware. “I’m not a machine,” she says. “I don’t have a desire to make multiples that are the same."

LELAND DUCK: Revive Upholstery & Design

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Before he moved to Portland and switched to upholstery, Leland Duck was a hot-rod specialist in Wyoming, chopping up classic cars with his father, an automotive welder. In 2009, after years of restitching the interiors of souped-up roadsters, Duck joined Portland’s crafty DIY ranks. “I take the same approach to furniture as I did with cars, bringing old things back to life,” the 27-year-old says.

Set above Beam & Anchor on N Interstate Avenue, Duck’s light-filled studio tumbles with swatches of old World War II tent fabric, thick tufts of foam stuffing, and the skeletons of 19th-century armchairs. “You tear open a vintage couch and it could be a nightmare inside, but as long as the bones aren’t destroyed, you can bring almost anything back,” he says. Duck combs estate sales for discarded furniture with potential, strips it down, and stitches in new life using distressed vintage fabrics, high-end threads from Denmark and New Zealand, and classic Pendleton wools. From hundred-year-old rocking chairs to contemporary inventions, Duck’s work is refined, precise, and practical.

Soon, Duck will launch a new line of vintage work wear–inspired furniture, taking his cues from Civil War–era uniforms and transplanting iconic button flies and leather elbow pads to cushioned recliners. “I’ve always loved the way jackets and coats are constructed,” says Duck. But it’s not all aesthetic. “Those little details are reinforcements for wear points,” he explains. “On a good old frame, they’ll last forever.”

MICHELLE STEINBACK: Cedar & Moss

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

When she quit as Schoolhouse Electric’s vice president for design and marketing in spring 2013, Michelle Steinback had no plans to launch a lighting company. She wanted a break—and anyway, she’d studied landscape architecture and had considered starting “a modernist Smith & Hawken.”

Then she bought a dilapidated midcentury house next to verdant Tryon Creek State Park. One small problem (beyond the mice): the renovation left her basement with no lighting. So Steinback began creating her own, swapping Schoolhouse’s Americana for Euro-accented modernism.

“There’s something very informative about designing for a specific project,” she says. “Under other circumstances, you might start with the big-statement chandelier. I had to design the small stuff first.” Last fall, that DIY project became Cedar & Moss. Design and fabrication happen in her basement. Despite the homespun scale, the company found a clientele eager for restrained lines and handcrafted textures, and Steinback hired her first employees in January. “I’m overwhelmed by how many lights we have to build,” she says. “I really believe we can grow but still have flexibility and balance. And we can always pull a table out on the deck and work in the forest.”

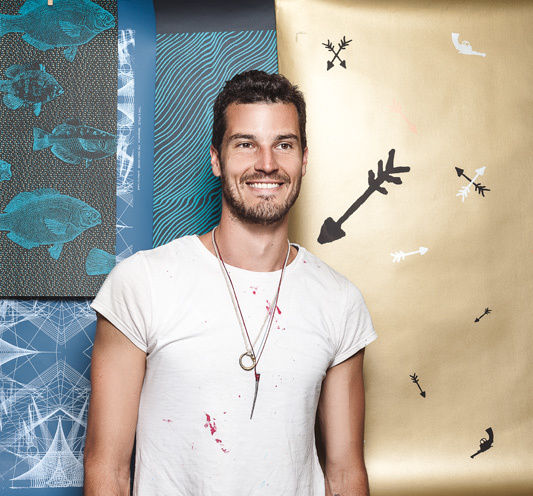

Nathan Reimer: the make house

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

After screen-printing tens of thousands of T-shirts over 10 years, it’s not surprising that Nathan Reimer has grown somewhat sick of the discardable slips of cotton. Looking to impress a more permanent print on the world, he has turned to another seemingly prosaic feature of everyday life: wallpaper.

“I love wallpaper because it’s integrated and becomes part of a space,” explains Reimer. “It’s kind of functional and kind of frivolous, but it feeds the texture of everyday life.”

With a long-standing interest in playing with patterns and loops using photography and audio editing software, the self-taught artist realized early in his printing career that he could make wallpaper using similar repeating patterns. But it wasn’t until he moved to Portland from LA three years ago and transformed an old house on Alberta into a shared retail and creative space called the Make House that he finally had the tools, space, and skills to experiment.

Reimer has since created eight different prints, ranging from futuristic geometric lines to richly textured fish drawings found in an ancient Webster’s Dictionary. His most popular print features images of cowboys and Indians inspired by the Internet and old National Geographics. Since he first sent out swatches last fall, Reimer’s work has been picked up by interior design stores and sites in New York, Philadelphia, Denver, and Japan.

While he now splits his time between consulting and wallpaper, he draws a firm line in his work. “The wallpaper is my art,” he says. “I’m not open to printing other people’s designs; I want to be working from my own ideas.”

BEN KLEBBA: Phloem Studio

After Ben Klebba left Chicago—where he had apprenticed for a luthier, working on guitars—he continued his education in wood and form with a cabinetmaking job in Portland. The company he worked for grew quickly during the real estate boom, and he got a firsthand course in small business. Then came the crash of 2008.

“Everyone got laid off,” he recalls. “And I thought, this is it. This is the time.”

While the world economy crumpled, Klebba launched his own furniture studio, Phloem. He devised a unifying system of angular components: his dressers, chairs, footstools, desks, and beds share a common geometry in their basic structural elements. “The whole point was to go through a process that led to a cool, sharp profile,” he says, “and make the process repeatable, setting a template we can use again. We make some sides, then we trap things between them.”

His furniture hits notes of urbane midcentury cool without slipping into retro pastiche. “I design for many different kinds of environments,” Klebba says. “I feel like our Peninsula chair could be in a really modernist steel cube of a house, or in an Old Portland house.” And while his palette of rich hardwoods and wool upholstery evokes luxury, Phloem’s disciplined reliance on a few key design elements recalls the company’s origins in gritty, thrifty times.

“Having a template frees you more than you would think,” Klebba says. “If you nurture that template, you can create an effect that’s somewhat similar to a musician’s or artist’s body of work. If you look at the whole thing, you see evolution, but you also see consistency and commonality and point of view.”

OVED VALADEZ: Industry

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Oved Valadez remembers seeing the original iPod in 2001 while studying to be a painter in Chicago. “The question of who delivered this—who delivered 1,000 songs to your pocket? I found that very intriguing,” Valadez recalls. He switched majors to industrial design.

“In order to truly connect with people, it’s not done through a painting,” he says. “It’s done through experiences, objects, products. This is the process of bringing something to life.”

Born outside of Guadalajara, Mexico, Valadez moved to Portland in 2004 to work for the design firm Ziba. In 2011, he and four other defectors left to form their own studio, Industry. From the company’s spare offices in Northwest Portland, Valadez has designed products and services for TDK, Nike, Starbucks, and Intel. Most recently, the firm created the “ultimate” urban bicycle for Oregon Manifest’s nationwide design competition: a maintenance-free ride with GPS navigation built into the frame, steering the cyclist with vibration only.

For Valadez, good design is as much about process as about ideas. Industry’s philosophy of “adaptive innovation” aims to move from abstract concepts to physical products as quickly as possible, relying heavily on 3-D printing and speedy prototyping. “A lot of the big agencies start with a linear process: a long, strategic point of view,” he says. “But you can’t just prototype on-screen. Having an object is the only way to do that. We quickly iterate. It’s naturally making things better.”