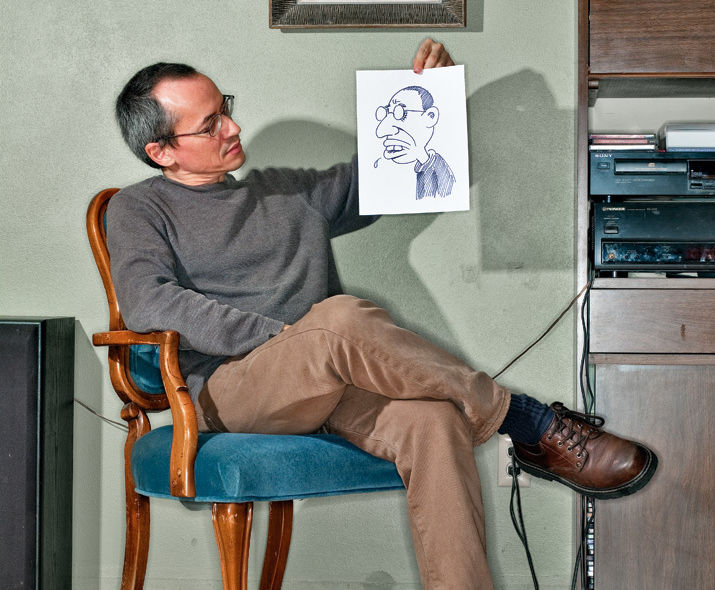

Behind the Lines

Joe Sacco and his cartoon alter ego in his Portland home.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

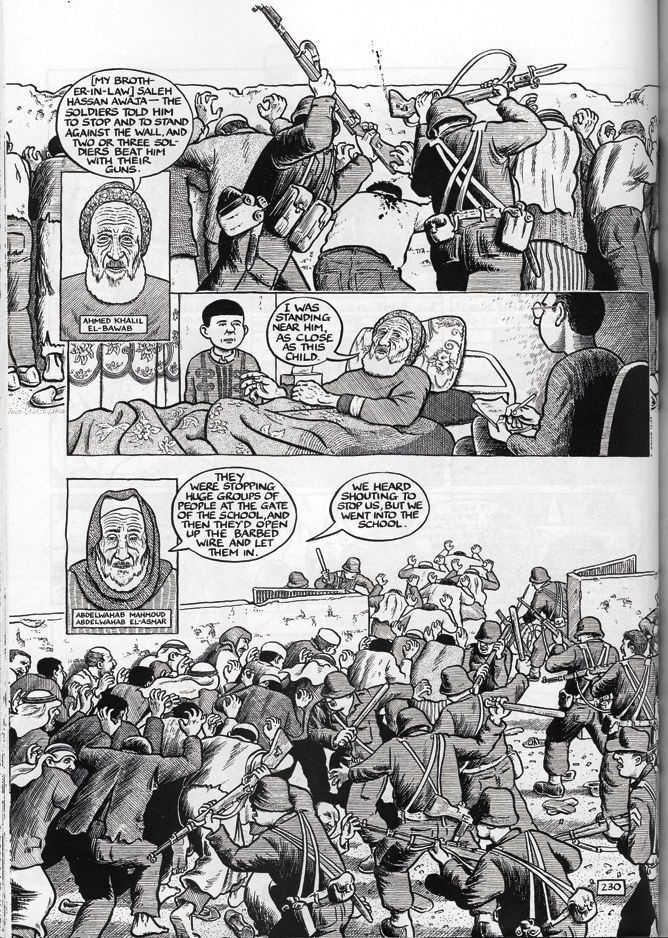

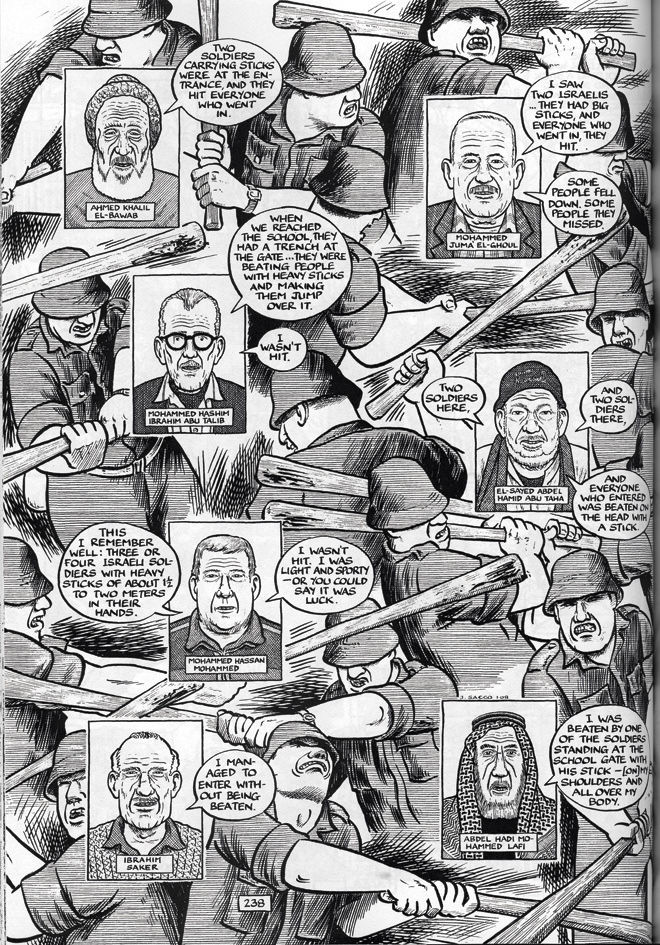

Nearly every day for seven years, Joe Sacco drew—frame by frame, letter by letter, crosshatch by crosshatch—a 390-page comic book reconstructing a story history had all but forgotten: the 1956 Israeli massacres of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Although suicide bombings, missile strikes, and surgical assassinations continue to be routine in this seemingly intractable conflict, Sacco chose to focus on two of the first attacks, Khan Younis and Rafah, which remain among the deadliest ever on Palestinian soil, even a half century later.

Sacco worked from interviews with witnesses, snapshots of the people and places today, and observations jotted in his notebook. He describes his technique as “extremely old-school”: laying down his first lines with No. 2 lead pencils on simple, two-ply Strathmore boards, followed by the careful strokes of a Speedball Crow Quill pen that has to be dipped in a jar of India ink every 30 seconds. The result is Footnotes in Gaza, hitting bookstores this month.

In the introduction to the American Book Award–winning Palestine —Sacco’s first book to merge comics and journalism—the Palestinian scholar Edward Said notes the artist’s keen eye for “history’s losers.” Drawn in pieces for the Guardian, the New York Times Magazine, and Harper’s, Sacco’s subjects have ranged from a Serbian wartime wheeler-dealer to the ragtag Iraqi army in Operation Iraqi Freedom. But Footnotes goes a step further, portraying not just the events that one Hamas official recalls as the moment that “planted hatred in our hearts” but also the elusive truth in the prismatic recollections of those who were there and survived.

Born in Malta, Sacco, 49, has lived in Australia, Germany, and New York City, but for the past seven years he has made Southeast Portland his home. With an assignment on African migrant workers in Malta penciled and awaiting ink, and a story on the poor of Camden, New Jersey, soon to commence, Sacco took a break to speak with Portland Monthly in his modest home office.

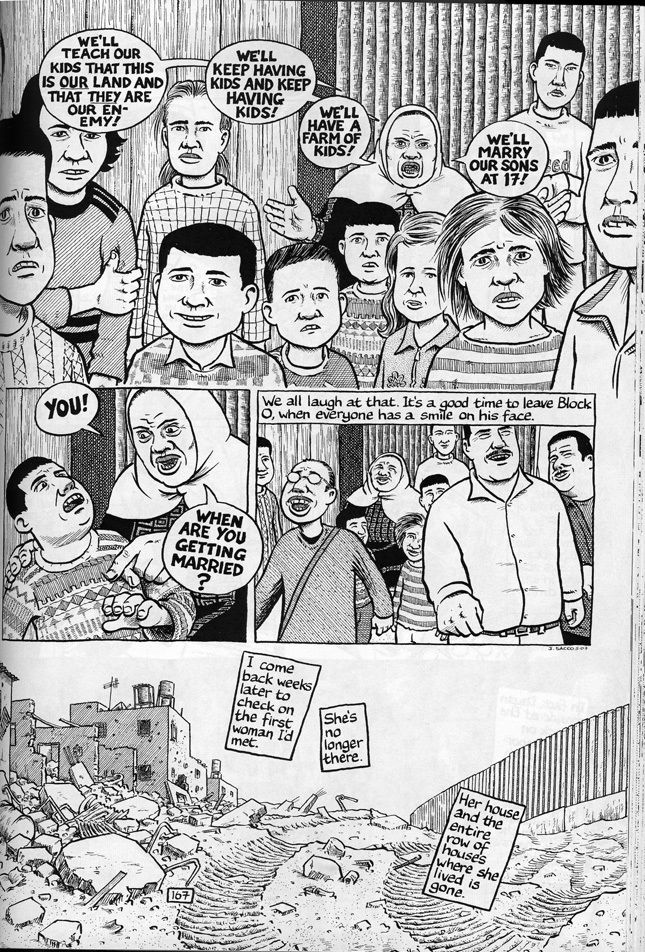

A moment of humor amid the violence in Footnotes in Gaza

Image: Joe Sacco

With all the current turmoil in the Middle East—the daily battles, the constant peace initiatives—why would you devote seven years of your life to a book about two events that happened 50 years ago?

Well, the short story is, in a United Nations document there is a reference to a couple of events in 1956 during the crisis over the Suez Canal when Israel conquered Egypt in the Gaza Strip. Both incidents involved a lot of casualties: the biggest killings of Palestinians on Palestinian soil—ever. The report gives an Israeli version and a Palestinian version, but leaves it at that, without making a conclusion. That seemed a bit odd. So I figured, why not find out what happened? The long story is in the book’s forward.

You spent time in Gaza in the early ’90s working on your first major book, Palestine. How had things changed when you returned a decade later to create Footnotes?

There’s always a new plateau of violence. At first it’s shocking, and then you grow accustomed to it. On my first visit, during the first Intifada, the violence was rocks and bullets. The last time, during the second Intifada, it was bombers, tanks, rock-propelled grenades, and mines. The suicide bombings in Israel at the time had kicked the whole thing up several notches.

The other thing that was really different was the amount of building that had gone on. Because of the Oslo Accords (a 1993 peace agreement), the Palestinians actually decided to spend their money and build on their property. No doubt many of them regretted it, because many of those homes were getting bulldozed by Israelis while I was there.

You’ve often had no mainstream media affiliation. Does that help or hurt you as a reporter?

I think it’s helped me, especially when I was starting out. You could say that because I had no backing, I wasn’t important. And I didn’t think of myself as that important. So I didn’t even try to approach the power brokers. If they want to talk, they’re going to talk to someone who’s going to trumpet what they’re saying. And I was useless in that respect. Because I had no money, I ended up living in hotels or getting rooms with people. And because I had no clout, I hung out in cafés. It wasn’t a thought-out concept, but I ended up finding stories that had nothing to do with the people who are making the decisions. My stories became about the people whose lives are being affected by the decisions.

When interviewing big fish, or even the regular people, how do you introduce yourself and your work? Is it, “I’m a cartoonist, but I’m serious”?

When I first started out, I was more self-conscious, so I was very careful about what I said.

But on these last trips, it was very useful to have my book Palestine with me. My guide would give it to each person before the interview. These were often older people who were not English speakers, but they could get what I was doing right away. They could open the book up and see themselves in the drawings. A book of prose wouldn’t mean anything to them.

Image: Joe Sacco

What keeps bringing you back to the Middle East?

I studied journalism at the University of Oregon and, it being an American university, what’s drummed into your head is “objectivity.” When I moved to Europe and began to see that the situation in the Middle East wasn’t quite like it was being presented by the US media, I was furious. American journalism is very self-congratulatory about its ability to tell two sides of the story. But it’s like watching a tennis game, where the ball is being hit back and forth by this spokesman to that spokesman. And then it’s up to the reader to decide. That didn’t seem a good model, especially in the Middle East. Clearly the Israeli point of view is very well represented, and the Palestinian point of view is not. I grew up with the notion that Palestinians were terrorists. Whenever I heard a Palestinian name, it was in relation to a hijacking or a bombing. There was never any context given. That was what really started to anger me once I realized what was really going on.

You graduated in 1981, when Bernstein and Woodward’s Watergate exposé was still blowing wind in journalism’s sails.

Yeah, in fact, it was hard to get a job because there were so many great journalism graduates around at that time.

You gigged with trade publications, worked on the Downtowner, and started a magazine …

[It was called] the Portland Permanent Press. It was comedy and satire. We interviewed visiting comedians.

But you had always drawn cartoons. When did you put the two pieces—journalism and cartooning—together?

Well, I had given up journalism and was trying to make a living in Berlin, mainly drawing album covers and posters. I toured Europe with a Portland band called the Miracle Workers, and I did a comic about that, writing down what they were saying and sketching them. That was a precursor. I had been interested in the Middle East for a while, but while in Berlin, I decided to go see what was happening for myself. And so I wouldn’t feel like I was wasting my own time, I decided to do some comics about it. I came out of that autobiographical tradition of cartooning, so it didn’t seem like much of a stretch. I thought, maybe I’ll talk to people, though I didn’t really think of it as “interviewing” at that time. But when I was there, all this journalistic stuff just kicked in. And suddenly I was taking notes, and being careful how I quoted people, and that sort of thing. Then I started thinking, “Oh, I’ve seen this part, but there’s this aspect or that aspect I should see.” And I started filling in the gaps. So, for example, I knew all the Palestinians’ ancient olive trees were being bulldozed by the Israelis, so I knew I should do something about that. I did not have a theory of comics and journalism, really, which is good. I think that’s why the first book (Palestine) will always seem kind of fresh.

Who is your audience?

When I first started out doing this, I thought, I’m going to cut my throat commercially. Who’s going to read a comic book about the Palestinians? And actually, as a comic book, it really failed. Over nine issues, the sales kept going down, worse and worse. It only succeeded when I put it into book form. After my Bosnia book came out (2000’s Safe Area Goražde), I realized there was an audience for it. With the rise of comics—not just because of me, but because other cartoonists were doing good work—it just seemed like comics reached this critical mass and I just happened to be there.

Image: Joe Sacco

Your portrayal of your subjects is so keenly observed and beautifully detailed. But your depictions of yourself are more cartoony and caricatured. Why?

That’s not really intentional, to be honest. When I started drawing the Palestine comics, everything I drew was very cartoony; everything was exaggerated. That was the only way I knew how to draw. At some point I realized, this is serious material, I need to be as representational as I can be, which isn’t that great, but I just sort of left my own character behind. Now it would seem so self-conscious to make myself look completely realistic that I just can’t bring myself to do it. People have also said the more nondescript it is, the easier it is for people to put themselves in my shoes.

For some of the rather intense stories you tell, it’s also comic relief.

Especially in Palestine. That book was very episodic. So I was the character who was tying everything together, and I was depicting myself in a way that was true: inexperienced and more apt to be neurotic, a bit panicky, and bumbling. I don’t depict myself in that way now because I’m much cooler in those situations.

It seems your character moved on as well, from neurotic bumbling to a deeper self-questioning?

Yes. One thing I want to do is sort of demystify the whole process of gathering a story, or reporting. There is doubt, and there are misgivings about what you’re doing. And I think you’re constantly weighing those things in your head. You’re judging yourself. And you’re aware of the seams in the story, those parts that aren’t quite fitting together. More and more, I want to confront the reader with that thing. The best way to do it is through myself, rather than pontificate the problems of journalism.

You not only cite Dispatches, Michael Herr’s 1977 book about the war in Vietnam, and Hunter S. Thompson as influences, but also George Orwell, who is largely forgotten as a journalist.

He did a lot of journalism. The Road to Wigan Pier was an inspiration because [Orwell] took a bed where the miners were sleeping. He wanted to get a taste of it. It’s also inspiring that he continued writing even though he was really sick—basically until he died. He lived this sort of lonely existence at the very end when he was writing Nineteen Eighty-Four on the island of Jura. It’s not really a question of romance, but it’s that sort of doggedness that I really appreciate.

It’s easy to see a kinship in your work with other cartoonists like Art Spiegelman and R. Crumb, but are there other artists, genres, or periods from which you’ve found inspiration?

I’ve always greatly admired the Flemish painters from the 16th and 17th centuries for their ability to capture life and, I think, for their ability to open a window on another world. You can recognize human beings doing things quite different than what you do in your life, but you just have this kinship with them. Their world is alive. I think especially of [Pieter] Bruegel the Elder. The solidness of the characters—they’re full of flesh somehow.

You once said the famed 1964 Clint Eastwood movie, A Fistful of Dollars, shaped your early style.

As soon as I watched that film, I went upstairs and started to draw in a different way. It was the close-ups and the ugliness. The faces are real, a little grotesque, which is something you find in Bruegel, too. I remember a face on one side and a lot of empty space on the other. That sort of stuff sticks with you when you’re a certain age.

Among the many Israeli critiques of your work I’ve read, I was particularly compelled by one: that all the Israeli soldiers are caricatures—big, blocky, and threatening. In general, the soldiers are less defined than the victims. Why?

I don’t think it’s conscious. With the soldiers, I always try to draw some who are a little ambivalent about what they’re doing and others who have worked themselves into a frenzy. I’m not trying to put myself into the role of an Israeli; I’m trying to put myself in the role of someone who’s brutalizing someone else: what goes through your mind, how you get yourself to hit or kick someone. I’ve felt that way, and I’m more likely to feel violent with someone who is cowering. It sort of infuriates me.

The only living Israeli you quoted at any length is Mordechai Bar-On, the right-hand man of renowned Israeli military leader Moshe Dayan. Did you search for other Israelis alive at the time?

If I had more time and more resources, I probably would have tracked down more people, knowing full well that the chance of someone saying something would be pretty minimal. I hired some Israeli researchers to go through the archives. One found things that helped me out. But at some point I realized this is like any history: it’s never really complete. What I would prefer is an Israeli historian following up on this with his or her point of view.

Which journalists do you think are most credibly covering the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today?

For reporting, Amira Hass. For commentary, Gideon Levy. Both write for Haaretz. Hass knows the foibles of the Palestinians, and she talks about them. Her reporting is consistently good.

You were born in Malta, spent your early years in Australia, and have lived in Berlin and New York. Why settle in Portland?

My dad got a job in Portland when I was 14. I went to Sunset High School. Those are always formative years, college and high school. Portland, in the last 10 years, quit chasing Seattle and just became Portland. There are things to do, but you can also be in your own space. As great as New York is, there is always someone coming through that you’re going to see, and you’re always a little hungover. You can’t really walk down the street and be lost in your thoughts like you can here.