Dark Journey

Carrying a supermarket rose, David “Joey” Pedersen walked to his mother’s apartment in Salem on May 24 last year. The sky, he recalls, was blue and white, vast and strange. He wore new slacks and a collared shirt. A cheap red tie bothered his neck, covering the tattooed initials of “Supreme White Power” that circle his throat. He marveled at the people, streets, and stores, sights he’d only imagined during his time in solitary confinement—11 of the almost 15 years he’d spent in various jails and prisons. He was 30, free for the first time since he was 16.

“It was surreal, being able to relax around people and not see them as a potential threat,” he recalls.

Pedersen’s new life was short. On September 26, he and girlfriend Holly Grigsby enacted a scene in Everett, Washington, that he later said he’d planned for years: Grigsby told detectives she slashed his stepmother’s throat, killing her; Pedersen killed his father, shooting him in the head. Then, driving through Oregon in his father’s car with the man’s body slumped in the front seat, Pedersen and Grigsby allegedly murdered Cody Myers, a 19-year-old from Lafayette who happened to be in Newport for a jazz festival, stole his car, and fled to California. The California Highway Patrol captured the couple on October 5, the same day Myers’s body was found in a forest near the Oregon coast. Police announced that Pedersen and Grigsby were also suspected in the racially motivated killing of a black California man named Reginald Clark.

The spree drew national media attention, especially after Grigsby told California detectives that she and Pedersen were headed to Sacramento to “kill … Jews.” Pedersen elaborated in a statement that police found in Myers’s car, which he later reprised in a letter: “May this act serve notice to all Zionist agents, here in America and abroad … that there exists yet a stout-hearted resistance to those forces seeking to destroy our race.” Authorities hint that the murder count could still climb. “All I can say is, they’ve only found four bodies,” says Craig Matheson, the prosecutor who worked Pedersen’s case in Everett. “The investigation is still very much ongoing.”

On March 16, the state of Washington handed Pedersen two life-without-parole sentences after he pleaded guilty to the Everett killings. While Grigsby faces a September trial in Everett, Pedersen currently lives in 23-hour lockdown at Washington’s Monroe Correctional Complex, awaiting possible extradition to Oregon and California. His lawyers say the federal Department of Justice may eventually take the tangled, tristate case.

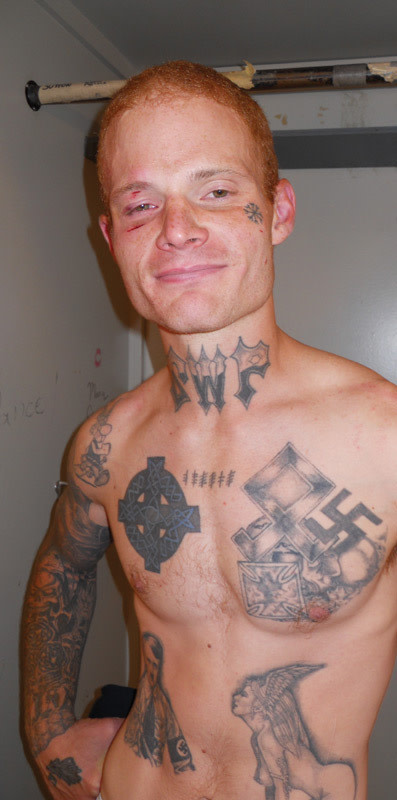

In his first teenage mugshot from the ’90s, Pedersen’s face is clear and handsome. Today, his occasional smile displays broken teeth, and his skin seems lost under a pernicious ivy of tattoos that range from Hitler’s face on his abdomen to a Viking battle symbol on his left cheekbone. In many statements, he shows no remorse for the murders. “When murder is necessary,” he’s told me, “it’s like taking out the trash.”

As the case unfolds in the courts, specialists in various fields say Pedersen’s transmogrification—from wayward teenager busted for stealing about $1,000 to unrepentant killer—was shaped at least in part by his prison experience. “A time bomb was created,” says Paul Frick, a youth behavioral specialist and former editor of the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. Frick sums up Pedersen’s incarceration as “15 years of training in how to be antisocial.”

Whether Frick’s view is right or wrong, Pedersen’s long record provides a case study in how Oregon handles both young offenders and hardened inmates. As the state’s politicians weigh reforms of sentencing and corrections, some experts say Oregon’s practices in both areas fall short of emerging consensus on how to handle serious criminals and protect the public.

THE CRIMES

I was an intern at the Oregonian when I first interviewed Pedersen, the weekend after his California arrest. (I have also attempted to contact Grigsby, but her most extensive response so far was a note: “This is on or off the record: fuck off, whore!!”) He was brazen then and throughout our correspondence of letters and phone calls. “Let me jump right into it, young lady,” he wrote to me recently. “I represent everything you have been … taught to loathe. I kill people. Given the opportunity at a ‘second chance’ out in society, I would change only my tactics.”

David “Joey” Pedersen as a third-grader

Pedersen spent his early childhood in Camp Pendleton, California, where his father and namesake, David Jones Pedersen, was a marine sergeant. In 2007, his mother sent a letter to the junior David Joseph (“Joey”) in prison, alleging that his father, remarried and living in Everett, molested Joey’s older sister. (His sister later told the media that the abuse did occur.) Pedersen says now that after receiving that letter he began planning to kill his father.

Pedersen’s mother, meanwhile, suffered multiple personality disorder, according to court records. When the couple divorced in 1993, neither parent sought custody of Pedersen or his sister. The siblings moved into the house of an aunt living in Stayton, Oregon. “Those were the best years of my life,” Pedersen tells me now. “Every holiday, she went all out…. There were people coming over. It was warm, and she baked Christmas cookies.” His favorite teacher sent him home with weekly behavior reports: “He was a bright, peppy kid. He never followed the rules, but he never hurt anybody….There was nothing malicious in him.”

Later, Pedersen’s mother offered to take the children back, and he moved to her Salem apartment. As a teenager, Pedersen ran with Salem kids who haunted the railroad tracks off of State Street, drinking Olde English and painting over local gang tags with pretend monikers. At 14, he began experiencing random panic attacks. A doctor at West Salem Clinic ultimately prescribed 200 milligrams of the antidepressant Zoloft daily, a “high normal” dose Pedersen kept taking through his incarceration. Classes at North Salem High School bored him, and he drifted into shoplifting, getting arrested and sent briefly to juvenile detention at 15. When Pedersen dropped out of school during his junior year, his mother kicked the 16-year-old out. He bussed tables to earn rent at the house of his restaurant manager’s brother.

“Joey was a pleaser,” says Tricia Penrose, his former manager. “He wanted everyone to like him, and everyone did like him.”

But in the fall of 1996, Pedersen quit his job at Old Country Buffet. Wanting money to take out girls, he says, he pointed a gun wrapped in a paper bag through the window of a coffee stand, taking about $600 in cash and personal checks from the college student working the register, who told police that Pedersen’s hands were shaking. (“Have a nice evening,” he called as he fled.) A couple of months later, he robbed another coffee stand and then a McDonald’s, using a gun that police later determined was not loaded. On January 13, 1997, he was arrested at the McDonald’s.

The sergeant who handcuffed Pedersen wrote in a report, “I took the suspect to my car and … he said, ‘The money … is in my left rear pocket.’ I patted him down for weapons and found, just as he had told me, cash wadded up in his back left pocket.”

THE PUNISHMENT

Two years before Pedersen’s robberies, Oregon voters transformed the system that dealt with young offenders. Like many states, Oregon was reeling from high crime rates in an era when then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani vowed to clean up New York City and President Bill Clinton’s landmark crime bill promised 100,000 new police officers on the streets. Juvenile gun homicides doubled nationwide between 1985 and 1995, and news reports warned of a rising generation of “super predators.” Forty-six states rewrote the laws to make it easier to punish minors as adults. This marked a significant departure: most countries rarely try youth under 18, or even 21, as adults.

In Oregon, an ambitious state representative named Kevin Mannix, a Democrat who would later turn Republican and run unsuccessfully for attorney general and governor, crafted a ballot measure that bound judges to specific minimum sentences for more than a dozen violent felonies. Measure 11 also decreed that youths older than 15 charged with one of the crimes enumerated by the act be tried—and, if convicted, sentenced—as adults.

Proponents of Measure 11 argued that judges too often used discretion to give lenient sentences. Mannix led the campaign with Steve Doell, whose 12-year-old daughter, Lisa, had been murdered by a 16-year-old stranger who served just 28 months.

“These are sentences for intentional, absolute use of force against innocent victims,” said an argument for the proposed law in the 1994 Voters’ Pamphlet. “Career criminals will learn that crime in Oregon does not pay.” Measure 11, promising to add over 6,000 beds to the state’s prisons, passed overwhelmingly.

Pedersen thus faced adult charges and adult time. He pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree robbery in a deal to reduce more serious charges, and Measure 11 dictated a 70-month sentence without parole. In the five years before Measure 11 was implemented, only 6 percent of juveniles who committed Pedersen’s crime were tried as adults.

In a routine assessment, the state Department of Corrections determined Pedersen’s potential for violence to be “slight.” Like all other young offenders convicted under Measure 11, he would serve his time in juvenile facilities unless he turned 25 before his sentence ended. He went to a space in Newport’s Lincoln County jail leased by the Oregon Youth Authority, where his situation soured. “If they’re going to treat me like an animal,” he wrote to a friend, “I’ll be one.”

Pedersen racked up nearly a dozen disciplinary reports, and as a result spent much of his time in his room or maximum-security units. Some reports seem trivial—for example, Pedersen and a counselor argued about Pedersen’s request for larger underwear. But Newport police were notified when Pedersen hit a fellow student. Following the assault, Pedersen told a counselor, “You’re wasting your time. Someone who wants to benefit from the juvenile system would be more deserving of your energy.”

Pedersen went to MacLaren Youth Correctional Institution in Woodburn. Though an intake test again found his potential for violence to be slight, the board overseeing juveniles urged a move to adult prison. MacLaren staff submitted a request to the Department of Corrections: “Please transfer [Pedersen] to adult corrections as soon as possible.”

PRISON

On June 18, 1997, his 17th birthday, the custody board granted MacLaren’s request and transferred Pedersen to an adult prison, Salem’s Oregon State Correctional Institution.

“I figured it would be less petty than juvenile prison, that there would be less silly rules,” says Pedersen now. “I was young and naive.”

In Oregon, a small percentage of young offenders are sent to adult prison, due to a failure to engage in treatment or because they pose a danger to staff and others—since 1995, less than 300 out of thousands in the youth authority’s custody. Even so, many mental health and corrections professionals contend that imprisoning juveniles alongside adults is always a mistake. (This year, Canada passed a law forbidding the practice.) Michael Caldwell, a psychologist, helped found Wisconsin’s innovative Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center in 1995. He researches aggressive mental-health therapy focused on connecting teens to family and school, conducted in secure juvenile-only facilities not unlike MacLaren. “Social bonds to conventional society make people behave in a conventional way,” Caldwell says. “These bonds give the person a realistic picture of themselves functioning well.” The Wisconsin facility has yielded promising results so far, with studies showing its “graduates” less likely to commit serious, violent crimes than peers released from other facilities.

A slim, 160-pound 17-year-old, Pedersen fought with older inmates. After eight days, he went into solitary confinement. Soon, the Department of Corrections petitioned the state’s custody board to return Pedersen to the juvenile system. The board denied the appeal, citing his “assaultive” behavior. “I just want to thank you for your help in trying to get me back to the juvenile system,” Pedersen wrote to his prison counselor. “I will try to make the best of my time here at OSCI once I get back in [the] general population.”

Over the following years, Pedersen was locked in his cell 23 hours a day and steeped in the violence of his surroundings. An inmate caught fire while being pepper-sprayed by officers in view of Pedersen’s food slot. “After he stopped writhing, they shackled him,” he recalls. In a letter to a friend, he recounted shaking hands with the Boxcar Killer, a notorious serial murderer found guilty of killing 34 drifters and homeless men.

Pedersen also befriended other convicts sent to prison before they were 18. There was Jeremy Roberts, who ran away at 13 and later started a riot at a juvenile detention center that earned him adult time. Gary Cavan was convicted of assault at 14 in 1996 and has been incarcerated ever since.

“All I really know is prison,” says Cavan today from a Texas facility. “What do they expect when they lock up young kids and throw them in the penitentiary? Are you not supposed to be bitter and filled with hate?”

The young men embraced white supremacy, an ideology found in prisons across the country. “We are men who hold strongly to the Aryan virtues of Honor and Integrity,” writes Alan Watkins, one of Pedersen’s friends, in a letter from the Snake River Correctional Institution in Ontario, Oregon. “Some time ago, I came to the realization that I would likely never get out of prison, and I determined that I would live my life on my own code.” In 1995, as an eighth-grader, Watkins was convicted of murdering his foster mother and sentenced to life. His cell was next to Pedersen’s at Snake River, and the two would talk for hours through a vent.

State corrections staff flagged Pedersen and his friends as associates of Aryan Soldiers, one prison gang out of 119 identified by the Oregon Department of Justice in a 2006 report. This particular clique is known to be more radical than other white supremacist prison gangs, according to Robb Anderson, a Multnomah County probation officer assigned to Aryan gang members. “Inside, it’s segregated,” says Anderson. “You have to join a gang to protect yourself, but [Pedersen] chose to involve himself with a group known for hardcore violence on the offense.”

THE HOLE

Pedersen participated in mixed-martial-arts bouts after his release from prison.

Pedersen's white supremacist ties, as well as about 70 violations noted in his Oregon corrections file, meant that he spent most of his time in solitary confinement. “If you’re known as an Aryan Soldier prospect or associate, you’re going to the hole and you’re never coming back,” says Dannel Larson, the estranged husband of Pedersen’s girlfriend Grigsby, who also served time in Oregon prisons.

In January 2000, Pedersen and two other inmates wrote threatening letters to Malheur County’s district attorney and two judges. (Pedersen says he was trying to break the monotony of prison. Dan Norris, the DA, says he was targeted because he prosecuted many white supremacists at Snake River.) About a year later, Pedersen assaulted an officer at Eastern Oregon Correctional Facility. He says his fantasies of violence “in the hole” boiled over when he beat the man with a hot iron. “I was waiting for a reason,” he says. “There were a lot of them who had it coming more than him, but he was there.” (He also claims he was shackled after the incident and beaten by guards, who broke his teeth. The Department of Corrections declined to comment.) In a letter addressed to a friend at Oregon State Penitentiary and confiscated by prison officials, Pedersen wrote that the guard’s “pathetic life was saved by an inmate…. As I had the pig on the floor in the corner, attempting to wack [sic] him again with the iron, this good convict slammed me from behind and used his considerable weight to pin me against the wall.” Soon after, Pedersen wrote ominous letters to the Idaho judge who sentenced white separatist Randy Weaver and to an Oregon prosecutor. Those threats earned him federal convictions and a transfer to the famed “Supermax” prison in Florence, Colorado, which houses the Unabomber, convicted 9/11 plotter Zacarias Moussaoui, and a collection of crime bosses.

Pedersen read constantly. He discovered a kindred soul in the prisoner-protagonist of his favorite book, Jack London’s 1915 novel The Star Rover. “Solitary confinement, they call it,” the fictional prisoner says. “Men who endure it, call it living death. But through these five years of death-in-life I managed to attain freedom … not only did I range the world, but I ranged time. They who immured me for petty years gave to me, all unwittingly, the largess of centuries.” Gazing at the crisp skies of Colorado, his cell’s only view, Pedersen recalls that he wandered alongside his fictional hero. “I’m always looking to get lost in exercise, or maybe a passionate pursuit (furious and frenzied letter-writing, perhaps),” he writes to me. “Even just walking back and forth in a memory.”

Similar supermax prisons, where inmates spend little or no time outside of cells, operate in 32 states, and solitary confinement is common across the country: the New York Times reported in March that America houses at least 25,000 prisoners in solitary confinement, more than any other democratic nation. The Oregon Department of Corrections holds more than 900 offenders in some form of segregation.

The repercussions of solitary confinement are a subject of increasing controversy. In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights stopped the extradition of four British terrorism suspects to the Colorado facility, saying conditions there should be studied as possibly inhumane. Roberts, one of Pedersen’s prison friends, says his own time in segregation has fostered dark obsessions. Currently housed at the Snake River prison, he’s allowed to leave his cell for 30 minutes five times a week—a typical schedule for a prisoner in solitary. “I sometimes fixate on the noises people make and wish I could hurt them to shut them up,” he writes. “For years, I fantasized about getting out of prison and hunting down and killing prison guards.”

Pedersen’s current lawyers retained Stuart Grassian, a former Harvard psychiatrist and one of America’s preeminent experts on forced seclusion. He was slated to speak at a hearing on the conditions of Pedersen’s confinement at Snohomish County jail, but Pedersen’s guilty plea precluded the testimony. “These abused criminals are not going to be shackled … forever,” he says. “They’ll be among us, and they’ll be as ill-prepared to survive—violent, impulsive—as we’ve made them.” In 1993, Grassian submitted a statement as part of the federal case Madrid v. Gomez, describing his findings on the practice. That lawsuit, on behalf of inmates at California’s Pelican Bay prison, ended with a US District Court’s ruling that prisoners in solitary confinement (among other punitive measures) had been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment.

In the face of mounting criticism, some corrections officials are rethinking solitary confinement.

“When you’re dealing with the worst of the worst, there has to be an underlying premise of having something positive to look forward to,” James Bruton, a retired warden of a notorious supermax facility in Minnesota, tells me. “Otherwise, they will [hurt] you.” Bruton’s 2004 book, The Big House, spells out a philosophy of rehabilitation that applies to even the most serious cases. “Ninety-five percent of prisoners get out, so you have to find a way to prepare them, and that means less time in the cell,” Bruton says now. Even when interacting with the most violent offenders, he adds, positive reinforcement is key. “You have to operate under the philosophy that being in prison is the punishment. It’s the court’s job to give a sentence. Making the experience worse is just cruel, and even dangerous.”

PROBATION

Pedersen and Holly Grigsby in September 2011

Near the anniversary of Pedersen’s release date, I walk up the narrow stairs to the attic closet where he first stayed when he left prison. The men who live in this small, drug-free group home run by the nonprofit Oxford House call Pedersen’s old refuge “the back cave.” His former roommate leads me through the kitchen, where a note on the refrigerator says “TO DO: Some girls.” He shows me the gazebo where Pedersen did hundreds of push-ups every morning. “Ready to move on and start a family,” Pedersen wrote in an intake questionnaire for Marion County’s probation office. Pedersen’s Oxford House roommate says he was friendly and well-liked, and spent his time looking for work. He also seemed to please his probation officers, though his county officer overrode his initial categorization as low-risk and instead designated him medium-risk. After Salem job prospects dried up, he received permission to move to Portland, where he settled at the Northeast home of a Measure 11 friend’s mother. A state parolee and a federal probationer, he reported dually to a Multnomah County office and to US Probation’s headquarters in Portland. He applied for jobs at 20 different Jiffy Lube locations. Meanwhile, he hung out with ex-convicts and traveled to the Oregon Coast and Reno, Nevada, to participate in three cage fights.

One September night, a Portland police officer responding to a carjacking in the Pearl District stopped Pedersen and another former Oregon prison inmate and took their names. He wasn’t arrested, but Pedersen says he panicked, certain he would be sent back to prison. “I figured I might as well make it worth it,” he says. He and 24-year-old Grigsby—another white supremacist former inmate he’d met through his ex-con friends—embarked on their fatal spree. Chris Whitlow, his Multnomah County probation officer, noted in a report that he became aware of Pedersen’s interstate travel (a parole violation) only after news broke of the Everett killings.

Whitlow declines to comment further, but colleagues say monitoring a case like Pedersen’s is a difficult task. Robb Anderson, the parole officer supervising Pedersen’s Pearl District companion and a specialist in parolees with white supremacist ties, says he knew the association would prove troublesome and worked to end it. “There’s only so much I can do,” he says. “I watch Fox News every night—I know I’m going to see somebody from my caseload. The severity of the damage these people go through in the corrections system, I don’t think the average person gets it. You can’t make cupcakes out of shit.”

The results of Pedersen’s actions were devastating. “Evil has no soul,” said Helen Clark, the stepdaughter of Pedersen’s stepmother, at Pedersen’s sentencing hearing in March. “The defendant is the epitome of evil.” Pedersen’s own sister called him a “sociopath.”

One member of the team who evaluated Pedersen’s competency to stand trial in February put it bluntly: “Once they created him, they should have just killed him, or never let him out.”

AFTERMATH

Pedersen’s mental-health evaluation from February describes him as an “intelligent, polite, well-spoken, funny, likeable young guy.” The report also notes that he exhibits narcissistic and antisocial traits. Our conversations and letters brim with poetry and literature, from Wordsworth to Styron. He says he’s anxious to gain access to music and television in prison, to watch Downton Abbey, the popular British costume drama. In one letter, he transcribed Yeats’s “The Song of Wandering Aengus” from memory and scrawled his own analysis in the margins—to be digested alongside his criticisms of “negrified” America.

Tough-on-crime proponents maintain that Pedersen’s original sentencing in 1997 and the correctional decisions afterward were appropriate. “Here’s the problem with all the stories,” says Steve Doell, the Measure 11 supporter who’s now president of Oregon’s Crime Victims United. “We focus so much on the criminal and their stories and their point of view. The academics would have you believe he was a really good guy who just happened to commit some armed robberies. We don’t live in Father Flanagan’s world, and this isn’t Boys Town. These violent teens need to be incarcerated and treated and corrected.”

“A guy like this was violent already and he would’ve been violent if we’d waited until he was 18 or later to send him to prison,” says Doug Harcleroad, an Oregon Anti-Crime Alliance policy adviser and former Lane County district attorney. “It’s about picking out the ones who can change and the ones who can’t. I believe he can’t.” Harcleroad adds that violent crime in the state has dropped by more than 50 percent since Measure 11 became law. (He also acknowledges that this decrease may involve myriad factors, like the passing of the crack-cocaine epidemic and the aging of baby boomers.)

Meanwhile, Oregon politicians are beginning to reconsider Measure 11. Last year, a commission appointed by Governor John Kitzhaber recommended overhauling sentencing laws—largely to save money—and Kitzhaber and legislative leaders appear likely to consider some kind of reform in the 2013 session. The new head of the state’s billion-dollar corrections department, Colette Peters, was appointed in part because of her success in improving the Oregon Youth Authority.

Pedersen insists that he acted independently. At his sentencing hearing in March, he repeatedly told the court that he asked for no leniency. Speculation about alternate outcomes would be just that. But the question remains whether the system aided public safety in his case. “Do you feel safer having these kids get out after many years of company with shady adult prisoners, or having the kid get out sooner but with appropriate services and better company?” says the National Center for Juvenile Justice’s Melissa Sickmund. “It would be great if the justice system had a mind-set like medicine: first, do no harm.”