Kinfolk Magazine Takes Over the World

The offices of Kinfolk—magazine, website, fast-growing global brand—hide behind a corner bodega and a half-block-long office building on NE MLK Jr. Boulevard. Coiled ivy frames the small white façade. A “KINFOLK” sign, with the same slender text as on the cover of each of the magazine’s issues, makes the place look like the most exclusive club in the universe.

Inside, dark wooden slats slice rays of natural light. Staffers stuff gift bags with silk-screened menus and colored paper, while others type busily in the glow of sleek Apple monitors. The unofficial dress code of neutral-toned linens and glossy, shoulder-length hair evokes American Gothic, as styled by a 21st-century fashionista.

The magazine, which a soft-spoken 27-year-old named Nathan Williams started three years ago with his wife and two friends, publishes only four issues annually, but as the sleek digs suggest, it’s no obscure underground zine. Over its short history, Kinfolk has managed to create a distinct ripple in the publishing world—it has a growing group of imitators and a solidly profitable, rapidly expanding circulation—and an aesthetic all its own.

The magazine’s tagline is “Discovering New Things to Cook, Make and Do” (originally, it was “A Guide for Small Gatherings”), and its articles and photos conjure a dreamy world of gorgeous organic meals, serious but convivial conversations among beautiful people, and cozy, well-fitting sweaters. The reigning vibe is aspirational but earnest. As Williams articulated in the editor’s note of his very first issue: “Mostly this magazine is all about inspiring one another to share our tables more often, to open our doors and hearts to family and friends—our Kinfolk.” The magazine’s visual vernacular of natural light and reclaimed wood speaks to a younger generation reared on craft cocktails and farm-to-table menus. The writing is often abstract and borderline didactic—but nobody picks up Kinfolk for its literary dexterity, anyway. Notably, there are no advertisements.

With couples across the nation now staging “Kinfolk-inspired” weddings, Williams has found himself at the center of a lifestyle movement of his own creation. Kinfolk has become the Velvet Underground of the modern publishing industry, wielding influence far beyond its size.

Nathan Williams, in Kinfolk’s Northeast Portland offices.

Image: Laura D'art

Nathan Williams comes from Magrath, a town of 3,000 in southern Alberta, Canada. In the tight-knit farming community, the high school graduates classes no bigger than 70 students, and the outdoors—river tubing in the summer, snow forts in the winter—provide the best diversion from ranching and oil rigging. In other words, a serious work ethic counts for more than a discerning eye for interior décor or lighting.

In 2008, Williams enrolled at Brigham Young University–Hawaii, a small offshoot of the Utah school. While following in the footsteps of his father, an economics professor (a career he considered “mature”), Williams began a personal blog which eventually attracted about 60,000 regular readers. He kept it up from 2008 until 2011, documenting dinner parties, summer playlists, and his proposal to girlfriend Katie Searle under a tea light–strung tree. His posts gradually included more artful portraits of intriguingly attractive people and unintentional-seeming still lifes, the visual hallmarks that now characterize Kinfolk.

In 2011, their final year at BYU, Nathan, Katie, and their closest friends, Doug and Paige Bischoff, began dreaming up a solution to what they saw as a serious gap in the publishing industry. In a bare-bones student housing apartment, the foursome plotted a magazine that would break the “millennial” mold—which they associated with bar hopping and clubbing—in favor of what Williams has since called “casual entertaining.”

“I would pick up Martha Stewart Living at the store looking for inspiration,” says Williams. “But I’m not interested in name cards or centerpieces. I’m more interested in the social elements of entertaining: the people, the conversations.” The name began as Kinsfolk & Company. “Kinsfolk is family,” explains Williams. “Company is the friends you invite into your home. That summed up the motivation for the magazine perfectly, but we thought it was too long, and we didn’t like the ampersand.”

That same year, Goldman Sachs, the titanic international investment firm, offered the freshly graduated Williams a job. By the time his plane landed in New York for a weeklong orientation session, Kinfolk’s first edition was nearing completion. Within Manhattan’s colossal Goldman Sachs Tower, while his fellow future traders and analysts sat in rapt attention, Williams stared into his iPad, riveted by a flurry of e-mail and web stats illustrating the new publication’s online debut.

Williams soon found out that Goldman corporate policy forbids involvement in public publishing projects. He faced a choice: stop working on Kinfolk, or walk away from the six-figure income he could expect to earn in high finance. He quit Goldman. “I did feel a little spooky,” he says. “It felt irresponsible, but right. I couldn’t imagine another week away from Kinfolk.”

The Internet validated his decision: within three weeks, the new magazine’s online page views ticked up to 6 million. “It was very surprising,” Williams recalls. “I couldn’t believe how quickly people found us.” The little team soon planned to expand on the first issue’s tiny press run.

In early 2012, Nathan, Katie, and the Bischoffs reunited in Lincoln City, Oregon; the Williamses migrated from Salt Lake City, where they’d moved after the Goldman departure. (Katie grew up in McMinnville.) From a basement office, Williams lugged stacks of the magazine’s second issue to the post office, wrapping 4,000 copies in butcher paper and twine. But by Volume Three—with sales growing quickly and a staff expanding beyond the founders—the oceanside command center became a logistical burden. In September 2012, the Kinfolk clan moved to a small yellow house on NE Broadway. By the time the MLK headquarters opened the following spring, there were 12 full-time employees, many of them Portland locals.

Today, Kinfolk stands serenely apart from the tumult battering print media. While former giants like Newsweek and Spin vanish, Martha Stewart lays off employees by the score, and Oprah suffers 22 percent drops in single-issue sales, Kinfolk thrives: a reported 55,000 copies sold for the Summer 2013 issue alone. The magazine’s $18 cover price, meanwhile, represents a complete reversal of the business model for most magazines (including this one), which sell advertising space to generate the vast majority of revenue and, effectively, subsidize prices for readers.

Nick Fauchald, a New York–based writer, editor, and publisher, has been in close contact with Williams since Kinfolk’s early days. “Kinfolk is a canary in the coal mine for independent publishing,” Fauchald says. “It’s an important step in a direction where we will be paying more for this type of product, as fewer mainstream magazines driven by advertising keep cover prices down.”

“Advertising would chop up Kinfolk’s message,” says Williams. “We try to think of the experience from cover to cover, always asking ourselves if the stories blend well and if the colors and the images feel like an intentional experience.”

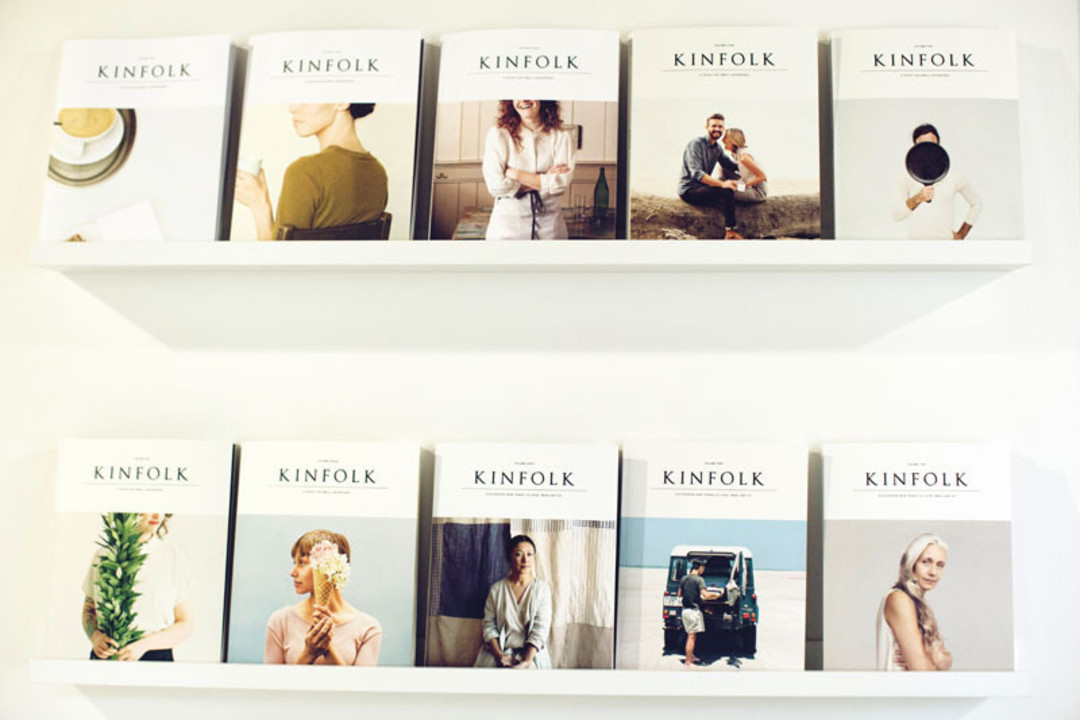

And Kinfolk is a beautiful magazine. Pick one up, and you’ll feel the smooth finish of 80-pound matte paper and the heft of 144 pages bound tightly to the spine. Its content is divided into sections labeled “One,” “Two,” or “Few,” and filled with narratives, lyrical essays, recipes, interviews, and personal stories.

But it’s the Kinfolk look that galvanizes the magazine’s rabid following: somewhere between the retro fantasies of film director Wes Anderson and an intensely curated Pinterest board. In any given issue, a reader might find cast-iron skillets, jam-filled mason jars, and stacked firewood, or a stunning spread of dahlias blooming out of an ice cream cone, all printed in gushing, vibrant ink on textured pages.

This combination sells well at specialty stores not known for their magazine selections. Upscale fashion retailers like Steven Alan and Anthropologie use Kinfolk to complement their wares; gourmet food stores champion the magazine’s rustic spreads; upscale home stores have stacked copies artfully on $10,000 coffee tables.

Meanwhile, “the Kinfolk look” has become pervasive in the design world. “Not long after they launched, you started seeing very similar magazines with very similar aesthetics and sensibilities, targeting a very similar audience,” explains Fauchald. “‘Kinfolk’ is an adjective to describe their type of photography now.”

Kate Bingaman-Burt is an assistant professor of graphic design at Portland State University and an illustrator whose loose, playful doodles grace the pages of national publications and corporate ad campaigns. She has watched the Kinfolk vibe become endemic in her classrooms. “Whenever we have a photo shoot, I get a lot of that soft focus and overhead shots of tables,” she says. “Kinfolk totally owns that aesthetic.”

The magazine’s website attracts about 175,000 unique visitors every month with a torrent of multimedia: city guides, transcendental photo galleries, and dreamy, Instagram-esque videos. One typical clip, part of a recurring series titled “Saturdays,” shows a pretty young couple in tasteful swimsuits diving into gray-green waters near Dougan Falls in Washington. They flip somersaults in sun-dappled water, and rest pensively, wordlessly, on boulders under towering Douglas firs. Yes, you want to be them.

Kinfolk succeeds in the American cities you might expect: Brooklyn, Austin, San Francisco. But in Japan, Kinfolk has gone gangbusters. There, the culture’s abiding fascinations with natural-lit photography and intimate gatherings fueled sales so encouraging—14,000 copies for the ninth issue—that Kinfolk launched a Japanese-language edition last June. “We were selling like crazy for the first two years,” Bischoff notes, “and nobody could even read the text.” Three more foreign editions followed for Russia, Korea, and China, all fully translated with locally relevant inserts. The magazine also reaches significant readerships in the UK, Scandinavia, and Australia.

In 2011, the Kinfolk crew recruited Julie Pointer, a quiet 28-year-old with steely eyes and a square jaw who did a graduate thesis, for a degree in applied craft and design, on mixed-media dinner parties. Pointer now orchestrates a key aspect of the nascent brand’s global campaign: organizing family-style dinners, honey harvests, nose-to-tail pig butchery workshops, and the like, around the world. She vets a “Kinfolk Ambassador” to guide each one, then sends them parcels filled with on-brand essentials: letterpress recipe cards, hand-stamped menus, and screen-printed posters.

“Instead of telling them exactly how we want to host the event, we show them,” Pointer explains. “It’s one thing to tell them not to use plastic containers. It’s another to send a beautifully packaged box with glass containers for making jam, or natural sponges and homemade cleaning spray. It becomes a sort of kit to model your workshop.” For between $50 and $80, Kinfolk fans dine communally under mason-jar installations and learn grassroots practices like preserving vegetables or throwing flower-picking potlucks.

The events are synchronized: when Pointer threw an instructional dinner on camp cooking and grilling, Kinfolk acolytes in 20 cities from Slovenia to New Zealand also experimented with hickory fire starters and haute s’mores. “Events are the core goal for us,” Williams says. “If we are going to be writing about this kind of stuff in the magazine, we can’t just talk about it, we have to actually do it.”

Considering such international proselytizing, it’s hard not to think of Kinfolk’s origins at a university run by the Mormon Church. The very notion of “kinfolk”—of community, bringing friends to break bread, of meditating on older ways—resonates with Mormon tradition as well as the broader vogue for all things artisanal. (It may be no coincidence that members of the church have become oddly prominent in design media in general: Google “Mormon mommy blogs” to meet a cadre of 20- and 30-something-year-old Mormon mothers who chronicle their crafty day-to-days.)

Kinfolk is definitely not a faith-based publication: the magazine covers coffee and alcohol, both traditionally off limits for Mormons. But even with religion stripped away, a certain missionary zeal remains. Take, for example, an article on gift-giving: “Learning to be a generous neighbor is a practice of tangibility, and simply changing your physical posture is a good place to begin.” Kinfolk preaches to its audience in a way that other indie publications do not.

“Maybe it influences us subconsciously,” Williams says. “But we aren’t pushing that sort of information on our readers at all.”

Where does a small-is-beautiful publication like Kinfolk go from here? How can it grow without resorting to advertising, either in traditional print or in the online ads now woven into the sites of Vice Magazine (Kinfolk’s millennial evil twin), the New Yorker, or Forbes?

Consumer demand does not seem to be a problem. Last fall, Kinfolk released a cookbook, The Kinfolk Table, now already in its fourth printing with more than 70,000 copies sold. This summer, the Kinfolk brand will extend to an online retail shop, selling carefully selected home goods and even a Kinfolk clothing line, manufactured in Japan, that promises “casual, comfort-oriented, subtly fashionable linens.” The company plans to open a physical flagship store in Japan this spring, with US outlets to follow.

On the other hand, Kinfolk seems to live most vividly in intangibles: dinners, events, and reader loyalty to the lifestyle the magazine has defined.

One evening last summer: Kinfolk holds a dinner at ADX, a Southeast Portland workshop where craftspeople and artists can rent space and borrow tools.

At long tables covered in butcher paper and lined with bouquets, each place setting has its own party favor: a linen bundle of scented fire starters secured by one long match, branded with the Kinfolk name. Chef Jason French prepares a campfire-themed menu from Ned Ludd, his Northeast Portland restaurant, while a local cocktail catering company, Merit Badge, mixes refreshments with names like “Pine Bramble” and “Smoke Fox.”

A middle-aged couple visiting from Paris tells me they jumped at the chance to attend while vacationing in Portland. Across the table, a tech-industry pair visiting from San Jose chimes in: “We just love dinner parties like this. They’re so ... Portland.” Soon the room is buzzing as diners dig into French’s harissa-spiced grilled lamb skewers, pausing occasionally to praise Kinfolk’s magnetic aesthetic.

But are these people ... kinfolk? They aren’t the Scandinavian beauties tiptoeing through tall grasses on the magazine’s pages, or the apron-clad youth coddling sourdough starters on its website. They may have boring full-time jobs and normal, dysfunctional families. They may throw flower-picking potlucks rarely—if ever. And yet they’ve come together around this little magazine from Portland that allows them to learn, commune, and live a certain considered life. Or, at least, imagine it.