The Scandalous History of Booze in Portland

Image: Oregon Historical Society

I. Pioneer Spirits

Step back in time and step right in, sons and daughters of Portland, to the first brick edifice ever built amid our mossy forest and muddy riverbank: 163 Front St. Italianate accents. Arched portals. Built for a settlement destined to prosper. Behind the counter, you’ll find Simeon Gannett Reed. In the back office, William Sargent Ladd. Ladd will make millions in banking, navigation, investment. Reed’s eventual fortune will fund a certain high-minded college. But at this misty moment—1853—their business is simple, and business is good. Business is booze.

Ladd arrived in Portland in ’51 with a load of wholesale liquor. Right about 1,000 thirsty souls lived here, but the enterprising New Englander soon wrote to suppliers for more product. Reed originally made his mark as “the best-dressed bartender in early-day Portland.” The wealth that enshrined both among the city’s founding fathers began in the bottom of a glass.

“Portland was largely populated by young, unmarried men,” Heather Arndt Anderson, author of 2015’s Portland: A Food Biography, said in an interview. “They had certain proclivities. Whores. Getting drunk. Family types only wanted to farm. So what was left were New Englanders who came to break away from their families. The only things to sell were dry goods and liquor.”

The first round was on them. Long before any artful craft cocktail inspired an Instagram post, Portland’s civic heart pumped sweet mother alcohol.

II. Power Drinking

In 1855, Anderson’s book reports, a decade-old boomtown of 6,000 boasted one drinking establishment for every 50 citizens. Saloons offered everything—dancing, singing, boxing, indoor pistol practice, Oregonian-advertised promises of attentive “young ladies.” German immigrants took one look at Oregon hop-growing country and the burgeoning market and fell in love. By the 1860s, most establishments sold the fine frothy brews of Herr Henry Weinhard, who “ran the beer game,” as Anderson puts it.

“If you couldn’t pay your beer bill, he’d become a partner in your company,” the author says. “If you still couldn’t pay, Weinhard would own your ass.”

In an isolated city, booze bestowed more than money—it meant power, and a succession of players parlayed liquor-trade status into public office. In the 1860s and ’70s, the Oro Fino Ring held sway, named for the plush joint co-owned by James Lappeus, near the Gem on First. Lappeus—onetime California gang member, and, yes, Portland’s chief of police—ran the city for a while, amid byzantine feuds for control. One of his successors, Jonathan Bourne, a Massachusetts ne’er-do-well, favored an extravagant 19th-century mustache and vivid political theater. By the 1890s, Bourne orchestrated Portland politics from the saloon-packed “North End,” tapping drunken sailors and lumberjacks for votes, muscle, and money.

In 1897, Bourne used North End money and “talent” to throw the most gloriously despicable party in Oregon history—in, of all places, Salem. For old-timey political reasons, he wanted to stall a legislative vote. So Bourne—himself a House member—transformed the capital’s Eldridge Block into a scene of debauchery, keeping our representatives drunk en masse. For 40 days. And definitely 40 nights. And it worked! “Bourne’s Harem” helped entrench Oregon’s national reputation as a whiskey-drenched moral sinkhole.

The forward-thinking solution was obvious: ban booze. Strange as it seems now, “temperance” advanced alongside progressive causes, particularly women’s suffrage. “There were very real reasons for women to be pro-temperance,” Anderson says. “It was still legal to beat your wife, for instance.”

The struggle was long, often turbulent. In 1874, “dry” activists (mostly female) waged open street battle with the very “wet” denizens (mostly male) of the Webfoot Saloon on First and Morrison: an obscenity-laced brawl, with knives and pistols drawn. Lappeus bestirred himself from the Oro Fino to arrest several

temperance ladies. It would take decades, and one of Oregon’s signal progressive moments, to settle the matter. In 1912, Oregon women won the vote, eight years ahead of the nation. In 1914, the long-held dream of dry reformers came true: Oregon outlawed alcohol.

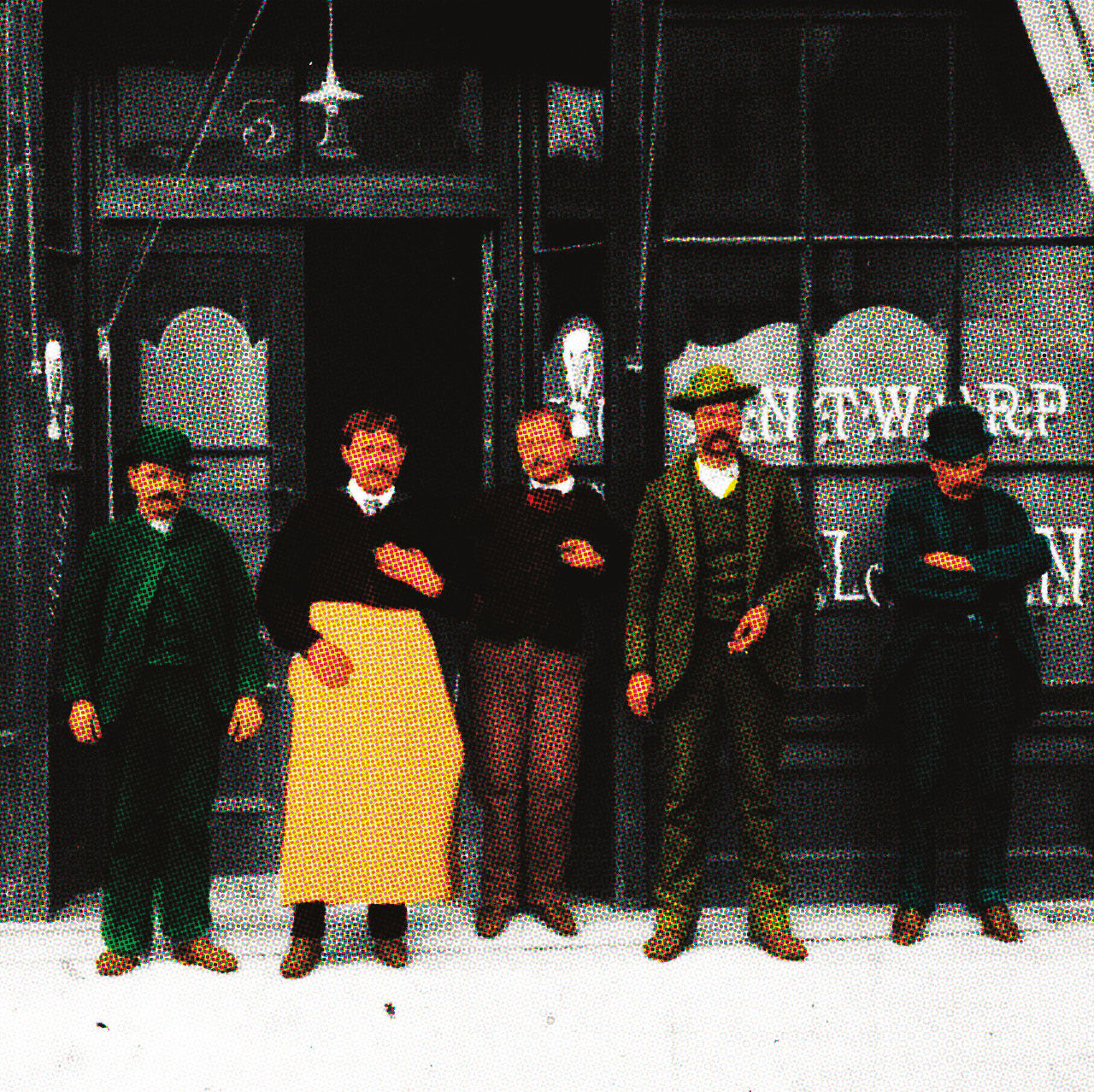

The fun-loving Finnish Temperance Union in 1889.

Image: Oregon Historical Society

III. The Experiment

Portlandian Prohibition began January 2, 1916, with a raid on a North Park Blocks premises run by a gentleman known as Birdlegs. Soon enough, though, Birdlegs was back in business in a roadhouse jazz club. The fun didn’t stop—it just reorganized.

“The city took over bootlegging,” says JD Chandler, whose forthcoming book Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland (co-written by Theresa Griffin Kennedy) tells the sordid tale. Theater owner George Baker—a racist and thuggish antiradical, but otherwise a real good-time Charlie—became mayor in 1917 and presided over one of history’s great speakeasy scenes. “Baker liked to put on a good show,” Chandler says. “Portland had a reputation as the driest city in America. But it was all a lie.”

Speakeasies paid off cops; city hall’s basement “evidence” room served as officialdom’s whiskey library. The Golden West Hotel—still there, on NW Broadway—anchored a bootlegging ring run by black railway workers, who brought in the best stuff. Sadie Martin operated a well-known joint at Hall and Sixth; she was chummy with the cops, who would occasionally use her place to engineer a convenient arrest. At downtown’s Morrison Hotel, Chandler recounts, a patron could check in to discover a whiskey bottle in the room, as if placed by an unseen hand, and receive a visit from a new female friend.

“They did raid the Morrison Hotel once,” Chandler says. “All 30 guys there said they were there to meet a friend.”

In 1976, an old Portland vice cop named Floyd Marsh published memoirs of the time. “There was crime in Portland, but it was regulated,” he wrote. Prohibition meant “a bigger, prosperous, and more violent underworld.” Marsh counted at least 100 speakeasies, 40 gambling dens, and a monthly bribe total of $100,000 (about $1.4 million today). Prohibition fostered not morality, but devilry on a grand scale.

In the election of 1932, Oregon voters defanged liquor enforcement. Prohibition ended nationally the next year, and with it died the feral formative era of Portland booze. The state created the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, the body that has ruled alcohol ever since—these days, in an orderly fashion that allows our brewers, distillers, winemakers, and high-concept taverners to thrive well within the law and sanity. (Most of the time.)

Does any ghost of those more unfettered days—from frontier whiskey to North End dives to loose-living speakeasies—live on? Maybe spiritually, in Portland’s instinctual yen for a good time, a night on the town, and a great drink.

“It seems like the rest of the country just found out about us,” Anderson says, “but we’ve been doing this for 150 years.”

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Gladys Carson and Edna Harr, convicted Portland moonshiners from 1923, each sentenced to a month in jail and a $100 fine; the Oro Fino (far right) was the stately center of political power in the 1870s; William S. Ladd, twice Portland’s mayor (and once its leading liquor purveyor) in his prime; power broker Jonathan Bourne in his bewhiskered younger years.