This is the Woman Who Saved Portland from the Black Death

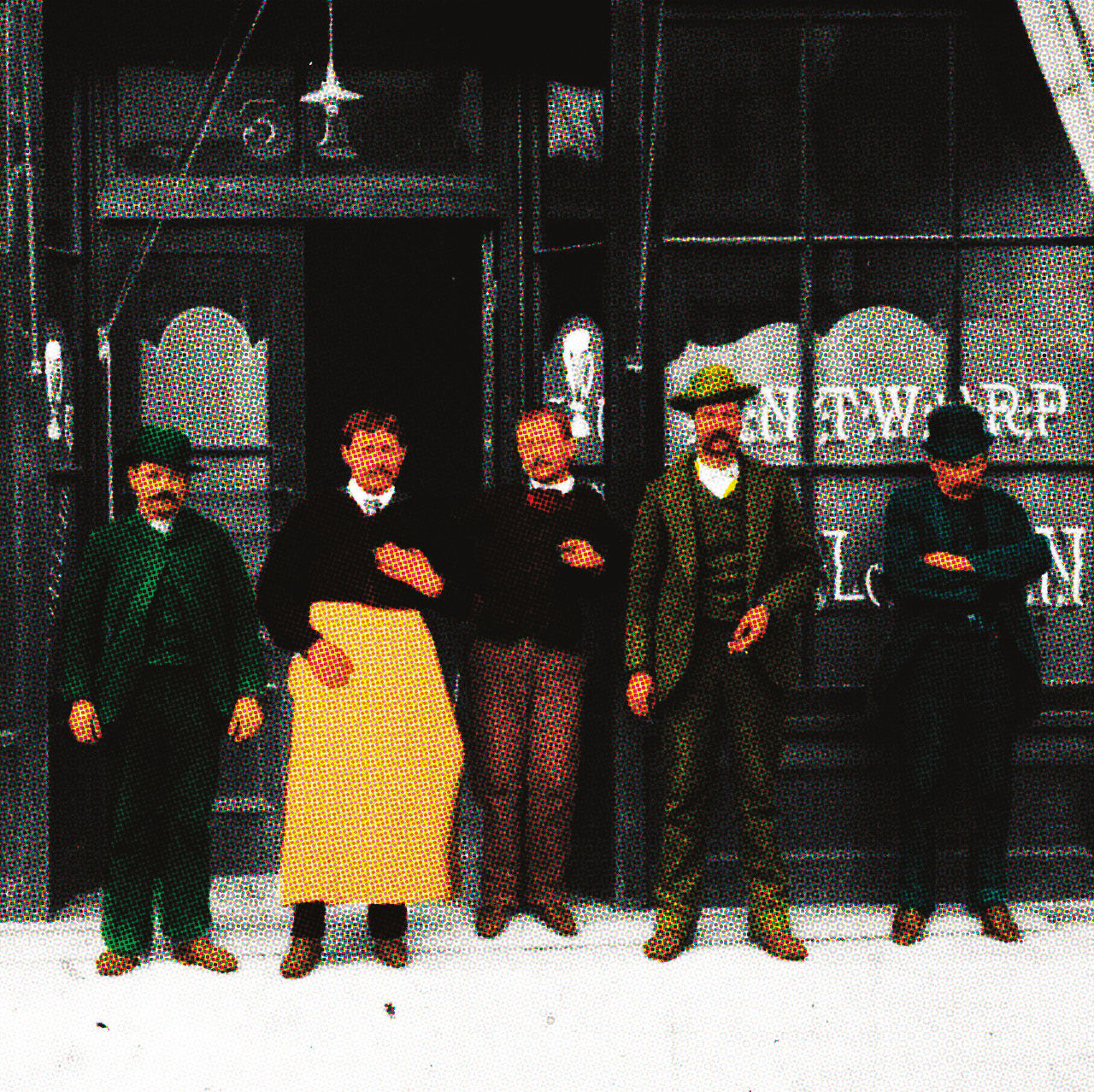

Photograph courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Dr. Esther Pohl knew what had to be done. The problem was, she’d never heard of it being done successfully.

Bubonic plague, the disease that killed a third of Medieval Europe during the 14th century, broke out in San Francisco in the summer of 1907. The City by the Bay had actually suffered a plague epidemic the previous winter, but the mayor, governor, and business tycoons staged a cover-up to avoid a costly quarantine. Now, the germ was back—plague always comes back—and there was no keeping it quiet. Every city on the West Coast was threatened.

In Portland, the coast’s principal grain port, rats (bearers of plague) swarmed the riverfront, feasting on rotting fruit and vegetables, garbage, and decaying meat. Speaking at the September 11, 1907, session of the city council, Pohl coolly reminded city leaders of a spinal meningitis outbreak just a few months earlier. “Now we are threatened with a much more dreadful disease,” she said. “We know that this plague is acquired and spread by rats and rat fleas.”

Portland had to kill all the rats.

Esther Pohl, born in a small Puget Sound lumber town in 1869, moved to East Portland at 13. She put herself through the University of Oregon’s Portland-based med school by working in department stores, hiding textbooks under the merchandise for study breaks. But she learned her most important lesson after graduation: in 1895, clean water began flowing from Bull Run Lake into Portland taps, replacing dirty river water. The typhoid rate plummeted overnight. “Here was a lesson in preventive medicine which none of us could forget,” Pohl later reflected.

In 1905, Mayor Harry Lane, a progressive doctor, recruited physicians for the Board of Health, including Pohl, who would soon take its reins. She was 35, methodical, and a savvy tactician, with direct eyes that caught her listeners. She monitored the diseases that threatened all cities at the time: smallpox, meningitis, typhoid, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, and tuberculosis.

Now she laid out the battle plan. Children earned five cents for each dead rat brought to the city incinerator: 1,600 were bountied that year. The Health Department’s market inspector, Sarah Evans, called down the law on butchers and cooks who left food and garbage unprotected from rats. Business leaders patrolled the waterfront, cajoling industry to play its part. Pohl’s pioneering cooperative attack worked better—and more cheaply—than anyone could have imagined: Portland suffered not a single plague death. Meanwhile, Seattle didn’t begin its anti-plague campaign in earnest until six victims had died. Two people fell ill in Vancouver, British Columbia, and San Francisco lost 77 while the city spent $600,000 in one year. Pohl’s total budget was $3,500.

Still, Pohl would later claim that Portland’s leaders scrambled to save the shipping trade rather than citizens’ lives. (In contrast, she cited the city’s patronizing air when local women demanded action on milk contamination.) “When that commerce-killing disease was imminent,” she said, “the action of the council was prompt.” Sometimes, dead rats are worth their weight in gold.

Want more gory details?

The hero: Oregon’s Doctor to the World, Esther Pohl bio, by Oregon historian Kimberly Jensen.

The villains: The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco, by Marilyn Chase.

Merilee Karr is a Portland-based science writer who blogs at True Science.