The Portland Newspaper Wars of the 1960s

Just before midnight on January 31, 1960, the headlights of a white 1957 Ford washed over a row of six newspaper delivery trucks parked against Oregon City’s Wymore Transfer Company shipping terminal. In a nearby alley, Eddie and Charles Snyder, lean 23-year-old twins with cropped dark hair, sat in a Volkswagen with their wives, waiting for the watchman to pass. They had six packages of dynamite stowed below the rear window.

The Ford hung a left and stopped at a tavern two blocks down. It was now or never. Charles’s wife jumped into the driver’s seat while the brothers fiddled with the dynamite. Charles touched a match to his charges. The seven-foot fuses smoldered at 45 seconds a foot. Eddie sprinted to the trucks, fuses sparking in his hands. It was a brisk 38-degree night, the parking lot slick with rain. One by one, he placed charges on the gas tanks of the delivery trucks, just behind the cabs. Running out of time, Charles tossed a charge under the fourth and fifth trucks.

“To hell with it,” Charles said “Let’s get out of here.”

Smoke poured from the fuses as Eddie and Charles dove back into the car. Around a sharp turn in Lake Oswego, the Snyders heard the explosions. Minutes later, they heard four more blasts, set by accomplices at another facility. They tuned the radio. KISN was reporting the explosions. “Jesus Christ,” one of the conspirators said. “I didn’t know it was going to cause this much excitement. Those things really blew.”

In total, they had destroyed 10 delivery trucks. Their target: the Oregonian.

The fuses for those blasts had been lit two months earlier. In November 1959, the Oregonian’s management decided to lay off three quarters of the newspaper’s stereotypers. Stereotypers cast the metal cylinders used in the giant printing presses that produced the paper—a costly and labor-intensive process that required four workers per machine. Now, management embraced cost-cutting and streamlining under the paper’s owner Sam Newhouse, known as the “newspaper collector,” who had acquired the Oregonian in 1950. Newhouse wanted to import automated machines from Germany that required just one operator.

The workers’ powerful union, naturally, had other ideas. At 5 a.m. on November 10, the last of 18 negotiations between the stereotypers and management deteriorated. Levi McDonald—the man who would soon hire Eddie, Charles, and their accomplices—walked out of the Oregonian building on SW Broadway and Jefferson along with 53 other members of the Stereotypers’ Local 49. The paper’s writers soon followed in solidarity—among them Wallace Turner, who won a Pulitzer in 1957 for exposés on ties among union leaders, mobsters, and city officials. Before long, the strikers’ ranks swelled to 850 newspaper workers from 11 unions—all of them angry, in some cases even calling for blood. When production manager (and owner’s cousin) Don Newhouse crossed the picket line outside the paper’s downtown headquarters, he heard, “We’ve got a bullet with your name on it!”

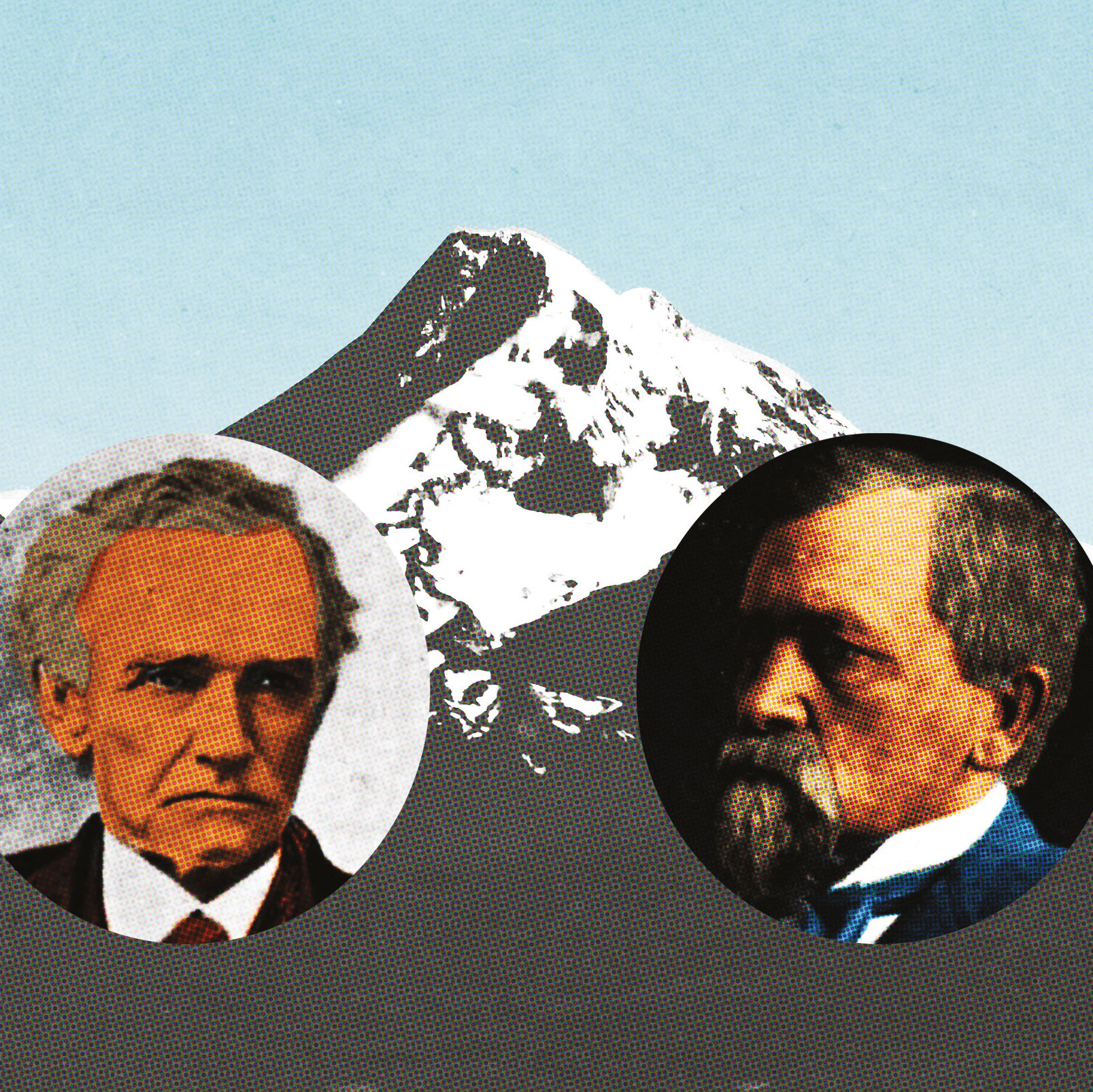

Sam Newhouse was not intimidated, however. At 65, the wrinkled, heavy-lidded businessman owned 19 papers, including the Denver Post, the Birmingham News, and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, giving him control over a combined circulation of 5.7 million daily copies. By 1962, Newhouse would own more papers than anyone in the United States. A shrewd monopolist, he crushed competitors, turning two-newspaper towns into one-newspaper towns.

Within 24 hours of the walkout, the Oregonian shipped in professional strikebreakers from Texas. Specialists in intimidation, the brutes left a bread crumb trail of police records as they scurried across the country to “rat” for big papers. Their presence in Portland was no more peaceful. One of them allegedly raped a 16-year-old Portland girl, breaking her jaw. Others packed a car with a small arsenal, complete with a 12-gauge and sawed-off shotgun, just in case. The stakes were high. Time called it “a finish fight, eyed closely...by newspaper publishers all over the US.”

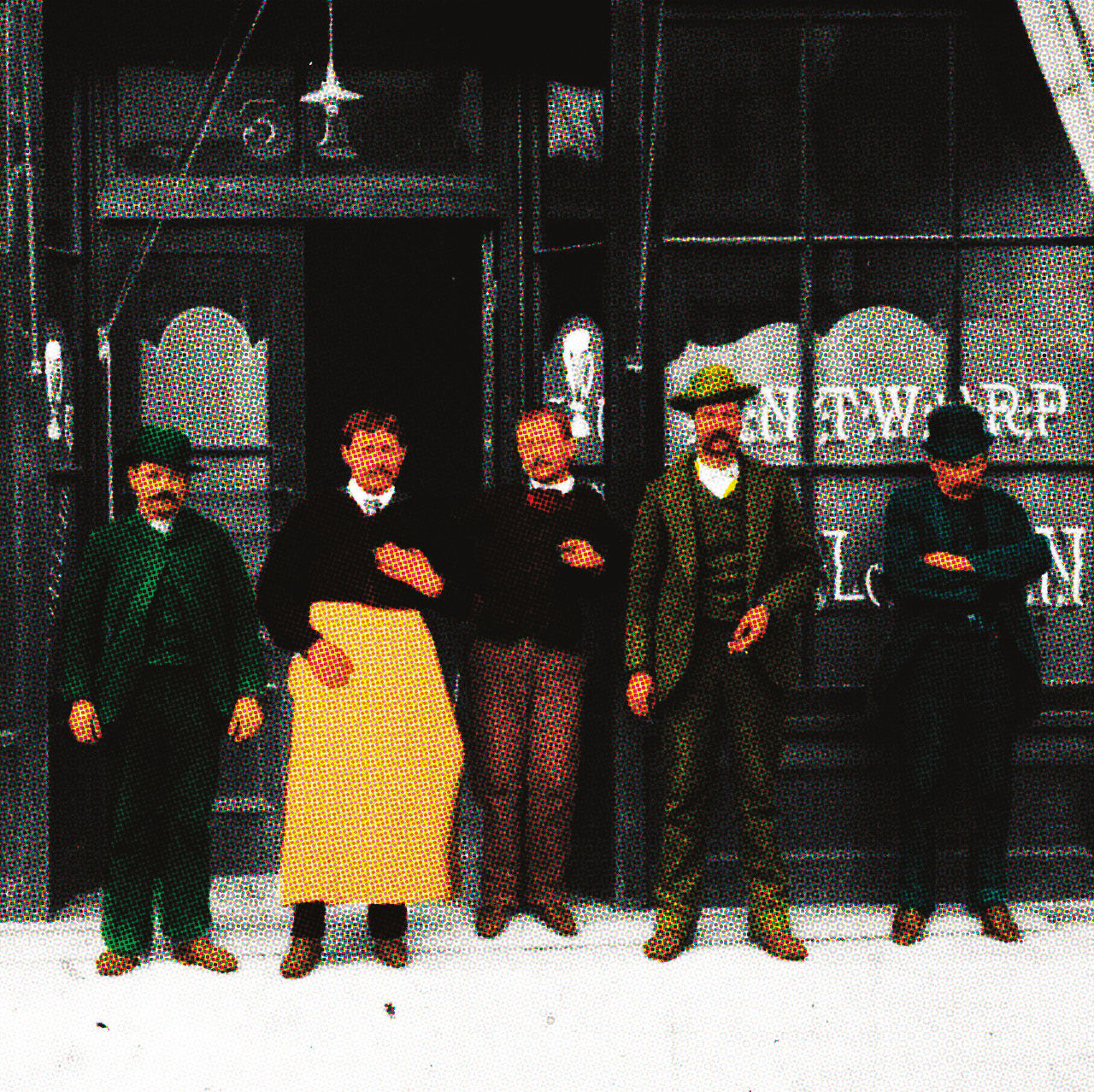

The strikers didn’t stand idle for long. On February 11, two weeks after the truck bombing, a small band of Oregonian discontents and disillusioned Pulitzer winners banded together to form the Portland Reporter. The rebel tabloid was founded in an eight-by-six-foot-cubicle, using an 1890 Hoe Press from Miami, salvaged by the International Typographical Union and dubbed “Little David.” Soon, the Reporter was churning out 60,000 eight-page papers every week. The skeleton staff juggled roles—mustachioed labor columnist Gene Klare, for instance, tripled as reporter, advertising sales manager, and promotions manager. Editors promised “a concise, readable report,” not a “propaganda weapon or a publicity medium” for the strike.

A few months later, the rebel paper secured a half-block, two-story former Wells Fargo stable at 1714 NW Overton St for its headquarters. Architect John Reese overhauled the manure pit and granary, and the newspaper rearmed with a “battery of linotype” and “gleaming, semi-automatic” stereotype machines. An arsenal of Associated Press teletypes brought in the wire news. The Reporter launched its daily press run.

Meanwhile, Oregonian readers reeled at a slew of typos and missed deliveries. “Some people must be awfully starved for a paper to pay full price for a supposedly daily which is only half there,” a reader named Ruth Zednik complained. “It’s obvious your best reporters, photographers, pressmen, etc., are putting out the new paper.”

The Oregonian retaliated in various ways. In May, for example, the establishment paper managed to lock Reporter journalists out of the room where the county’s primary election results were posted; the director of the strike called the move “a clear attempt ... to destroy the Reporter.”

Return fire came, quite literally, on October 16, 1960, when Don Newhouse, the local face of the national news empire, was shot with a shotgun by an unidentified gunman standing outside his house. Newhouse took 100 pellets, losing a hip and leg. The paper offered a $5,000 reward for information, but no one was ever arrested. The effects on the strikers and the Reporter were largely negative. Years later, Oregonian columnist Steve Duin would write that the shooting “knocked the strikers off their moral high ground.”

Even so, the strike and the upstart competition wounded the mighty Oregonian. At the height of the battle with its workers, the paper saw its circulation drop by 70,000 copies from its previous mark of nearly a quarter-million daily. Newhouse found himself forced to use his biggest weapon: his pocketbook. He purchased the Oregon Journal, Portland’s long-running afternoon paper, and its circulation of 190,000 for $8 million. Under the masthead the Oregonian-Oregon Journal, a temporarily combined paper reached as far as Florida for scabs. Newhouse enticed readers by giving away stuffed elephants.

Meanwhile, strikers canvassed the city, knocking on doors and imploring residents to cancel Oregonian subscriptions and switch to the Reporter. From Little David’s modest 60,000 weeklies, circulation peaked at 78,000 daily editions.

The Reporter had one strength Newhouse couldn’t match: a reputation as a beacon for the emerging political left in Oregon. Reporters Robert McBride and Dan Goldy hiked into the heart of the Rogue River National Forest to expose a fraudulent 460-acre timber grab. The Reporter sympathized with hillside homeowners who faced the loss of picturesque views if skyscraper apartments were built below them, and revealed that Portland, alone among major US cities, was neglecting public transportation problems.

As champion of the public interest, the Reporter earned the backing of Oregon’s two senators, Maurine Neuberger and pacifist Wayne Morse, who would go on to be one of the Senate’s two dissenters on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution escalating the Vietnam War. The nation’s press associations also took note. Walter Mattila won a Thomas L. Stokes award; photographers Pete Liddell and Al Jessen won awards in the Associated Press’s annual Northwest photographic contest; outdoor editor Fred Goetz bested Oregon’s top outdoor writers for the Izaak Walton League’s Golden Beaver; and women’s news editor Helen Lachman won a national prize for “her handsome layout, with Ray Wing photos, of fall fashions in women’s shoes.” The Rose Festival Association gave the Reporter a plaque for community effort.

1964 was a frightening year for labor in the news business. Publishing giants were devouring small papers across the country. The Chicago Tribune Company swallowed a combined circulation of 26 million, followed by Hearst and Newhouse with 18 million each. The AP warned that circulation and advertising revenues in most towns could feed only one paper. Distraught congressmen ordered special hearings on preventing newspaper collapse.

New technology was also doing its part to undermine the underdogs. In Orlando, New York, and Los Angeles, publishers fired up RCA and IBM typesetting computers, while offset presses replaced stereotypers with unskilled workers.

In February 1964, on a Sunday meeting in a board member’s home, Webb mounted a desk to announce the Reporter’s imminent closing. On Monday, March 2, the AP announced, “The Reporter is dead.”

In practice, the paper’s death throes would drag on for seven more months, until late September. In the mechanical department, Gus Brandt marked his date book with daily progress reports, always in black or blue ink. On September 29, in red, underlined twice, he scrawled “turmoil.” The next day:

44 pages.

Last edition out today

It was fun

So long,

—Gus Brandt

On October 1, $536,000 in the red, the Reporter folded. Some Reporter staffers suspected Newhouse provoked the strike in the first place, intending to crush union power and win a newspaper monopoly in Portland. If that was indeed the goal, Newhouse achieved it. The year prior, the National Labor Relations Board ruled against the validity of the Portland strike, the third-longest in the history of US newspapers. The ruling made the strike illegal and undermined the authority of the strikers.

Even in 1964, journalists warned that monopoly journalism would elevate profit above the public interest. Arguably, developments in 21st-century Portland have proved them right. Over the past few years, the Oregonian—owned by Advance, the corporation created by the Newhouses—has scaled back its print operation, sold its headquarters and presses, and laid off veteran reporters in waves. Those moves, of course, are just local manifestations of the deep transformation of media. While the Oregonian’s online readership is numerically larger than its print readership ever was, its role in Portland’s public life is unquestionably diminished. Amid myriad sources of information and opinion, authoritative, citywide coverage has lost its primacy.

As for the Snyder brothers who blew up the Oregonian’s delivery trucks, the end was no happier. “We all got short of money,” Eddie confessed. “I wish somebody had paid us not to blow the trucks up.” The jury sent Gerry Couzens, an accomplice, to prison for nine months; Eddie, four years, seven months. Levi McDonald, the instigator, got 10 years and a $500 fine.

Media has changed in ways no one could predict during the Reporter’s brief glory days. But the defeated strikers did foresee dire consequences. “Death of a newspaper is very tragic for us alone, but mostly for the community,” wrote the Reporter’s Robert J. Davis. “These dedicated men—on the last frontier of the independent newspaper—are silent this morning, choked with a feeling they are completely unable to express.”