Why Portland’s Elected Leaders Keep Failing Despite the City’s Success

Mayor of Portland should be a pretty sweet gig. Yes, the hours are horrible: Charlie Hales sleeps next to a phone and pager which could buzz at any hour if, say, the police shoot someone. The money’s not great. Any high-rolling CEO could pat the mayor’s annual $130,000 affectionately on the head.

Still, cool job. Hales addressed colleagues from around the globe at the Paris climate summit. He met the Pope. He got face time with Obama. The leader of a city renowned for sustainability, planning, and overall organic righteousness enjoys definite nerd-cool.

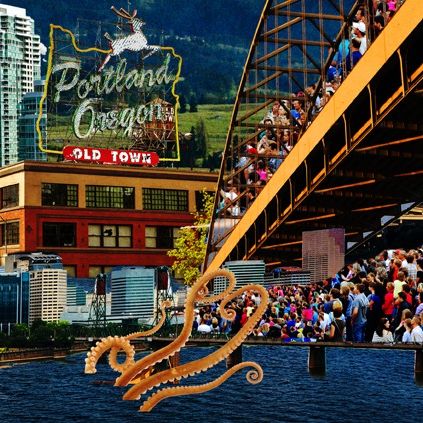

And yet—like Game of Thrones in reverse, thankfully with less sex—Portland’s mayoralty has become a crown no one wants to keep. May’s primary will be the fourth straight with no incumbent. Last fall, Hales became the third consecutive mayor to bow out after a single term. Despite an era of economic success, population growth, and cultural acclaim unparalleled in the city’s history, Portland’s top job seems politically jinxed. Vera Katz, the last mayor to achieve (or even seek) reelection, first won the office in 1992. Twenty-four years ago.

Yes, modern times. (Talk to any elected official about 21st-century civic discourse, and they will look at you like, This is why we can’t have nice things.) But in a thriving city full of government-loving liberals, success shouldn’t be this elusive. But maybe no one knows what success looks like anymore.

I visited Hales on a gray November day when City Hall bore a particularly dour look. A lone protester wearing a Guy Fawkes mask lurked creepily by the building’s organic garden, where kale grows without irony.

The mayor was in a chipper mood all the same; that he’d just aborted his reelection campaign seemed only to delight him. “It’s a sweet freedom,” he said, adding that he could now concentrate on getting things done. I asked Hales to consider these repeated abdications. Katz retired after three terms. But then Tom Potter, an avuncular ex-police chief, seemed to lose interest in politics shortly after taking office. Sam Adams, a trailblazer as the city’s first gay mayor, never recovered from a retrospectively trivial sex scandal. Hales—though he declined to specify this as a reason—faced a daunting challenge from state treasurer Ted Wheeler.

Circumstances aside, what is going on?

“People are frustrated with politics,” Hales said, “And they don’t distinguish between dysfunctional Congress and local government working well. Look at Salt Lake City—a city that used to be OK and now is great, but their mayor, Ralph Becker, loses his

reelection. Did success land on Ralph’s shoulders like a warm glow? No.”

Hales presided over a roaring economy, which added jobs at a clip not seen since 1999. The skyline shot up, and the construction boom flooded public coffers with new tax revenue. And Portland kept right on being cool, attracting thousands of migrants and high-profile business coups—an Airbnb office, Under Armour’s design headquarters, and so on.

Yet everyone seemed mad. Renters faced crushing increases and an instantly notorious 2015 “wave” of evictions. Home prices rocketed, old buildings fell. A lot of semimaudlin talk about “Old Portland” made the rounds, as did vague dread of “tech money,” and Portland’s reactionary side manifested: as workers demolished one decrepit SE Hawthorne house to make way for apartments, protesters shouted (as Willamette Week reported) “go home, fascist pigs.”

But the underlying miseries were real. So was anxiety that a beloved Portland—a low-key city where today’s median household income of $53,000 made sense—was dying.

Hales couldn’t master the moment. But could any mayor? In Portland, unlike any other major US city, the city council’s five commissioners, all elected citywide, share control of the various bureaus. They’re almost equals. This does not stop citizens from judging the mayor as, well, the mayor. “The position seems to have responsibility for people’s lives,” says Carl Abbott, a longtime historian of Portland and urban politics. “When snowy roads don’t get plowed, no one blames the governor.”

In reality, the post offers limited power. “You’re not dictator, and you’re not king,” says commissioner Nick Fish. “You’re barely the mayor. You don’t directly run two-thirds of the city, and if you want to get anything done, you need at least two other votes.”

In our system, the five commissioners must take grown-up responsibility for real things like water, emergency services, and building permits, and must cooperate. We don’t get strongmen on the order of Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, or Left Coast firebrands like Kshama Sawant, the India-born socialist on Seattle’s city council. Portland politics traditionally has a very managerial feel, a mode which ordinarily serves the city well. These may not be ordinary times, however.

“The city has grown,” Abbott observes, “but the leadership has been drawn from the same class of leaders, more or less, since the ’70s.”

The bookstore Reading Frenzy, specializing in small-press books and indie zines, operates in a row of North Mississippi storefronts that seems to encapsulate endangered artsy Portland: record store, avant-gallery, guitar shop. Early in 2016, owner Chloe Eudaly met me in Reading Frenzy’s back room, which she was converting into the headquarters of a city council campaign.

Eudaly, 45, had just Facebook-announced a bid to unseat first-term commissioner Steve Novick. I’ve known Eudaly for 17 years. When I first heard she was running for council, the idea struck me, frankly, as slightly far-fetched. But as we talked, I realized that impression was just a by-product of exactly the sameness Carl Abbott was talking about. Eudaly just doesn’t seem very “Portland City Council,” a milieu so white, male, and middle-class, it’s like 1962 never ended. She’s a single mom with no college degree, publicly known (to a small slice of the city) as a purveyor of punk chapbooks and, more recently, for starting an online housing activist forum originally called That’s a Goddamnned Shed. Her life in public advocacy began when her now-15-year-old son was diagnosed with a disability shortly after birth. “My mission from then on was to make life better for families like us,” she said.

Meanwhile, Eudaly experienced the dark side of Portland’s gilded age. In 2007, she was evicted from her home of 18 years. In 2008, her rent rose 50 percent. “I moved to yet a smaller house, further from the center city,” she said. “My rent has gone up 60 percent over four years.” By her reckoning this makes her one of about 150,000 Portlanders who count as “cost-burdened” renters. And in 2013, her shop lost its longtime downtown home—“due to gentrification,” its website bluntly claims.

This does not make an obvious résumé for a council that typically welcomes connected pragmatists, not battling outsiders. (Citywide elections are hard to win.) Then again, maybe a fresh perspective would be good right now. Eudaly spoke of the plight of working- and middle-class Portland. “Rents are rising two times faster than personal income,” she said. “I’ve never felt class divisions as strongly as I do now. This is happening all over the world, but it’s hitting Portland hard. Are we going to push an entire income stratum to the outskirts?”

Could she win? No idea. (Novick, her incumbent opponent and a lifelong liberal policy wonk, does not exactly read as The Man.) But even if she turns out not to be the answer, Eudaly is asking the right questions. If the next mayor (with those beloved council colleagues, of course) can fashion answers, he or she will be a great leader and the city will be saved. No pressure.

In ’60s and ’70s Portland, big thinkers wanted to rip out huge strips of Southeast to build the so-called Mount Hood Freeway. Downtown looked desperate. Abandoned houses pocked neighborhoods now coveted. Suburban sprawl gobbled the countryside.

In response, Portland took dramatic ideas—light rail and streetcars, limited sprawl, dense new neighborhoods—and armored them in impregnably boring process. Have you read the 1972 Downtown Plan? The 1980 Comp Plan? The 1996 Bicycle Master Plan? No, you’re just living in them.

That approach to creating great urban space largely worked—everyone wants to move here. But it’s no longer enough. Some planners predict the metro area could add 725,000 people over the next 20 years. Around the world, income inequality and the demand stocked by urban migration are making city life exhaustingly expensive for ordinary people. Portland needs to amend its vision: to be the city (maybe the only city in a globally desired place like the US West Coast) that weaves affordability, access, and opportunity into all its progressive urbanism.

Wheeler and county commissioner Jules Bailey, the consensus early frontrunners for Hales’s job, are both political insiders. But in early campaign interviews, both acknowledged that business as usual won’t cut it anymore. In fact, they said strikingly similar things.

Bailey: “We need a conversation about who we are as we become a major city. Mayor of Portland is one of the most powerful positions in the entire state to convene that conversation.”

Wheeler: “The biggest role for the next mayor is to lay the foundation for the next 20 years. What will this city look like with another million people in it?”

The specifics will emerge (or not) only through a campaign that could last until November if no candidate tops 50 percent next month. And then, for the winner, comes the task of being the mayor: even in Portland, a job uniquely designed—maybe cursed—to hold politics’ center ground.

Ask the guy who’s leaving. “It’s your whole life,” Hales offered, as advice to the next contestant. “It’s your family’s whole life, and that’s the deal. And this may sound simplistic, but it’s how I feel: Own it. You are the center of the storm. Own it.”