The Spirit of '77: How the Blazers Won Portland

Game One: Philadelphia / May 22, 1977

No three-point line. No amplified music. Timeouts hum with human voices. Players’ short shorts and tight jerseys make them look even taller, even more intimidating.

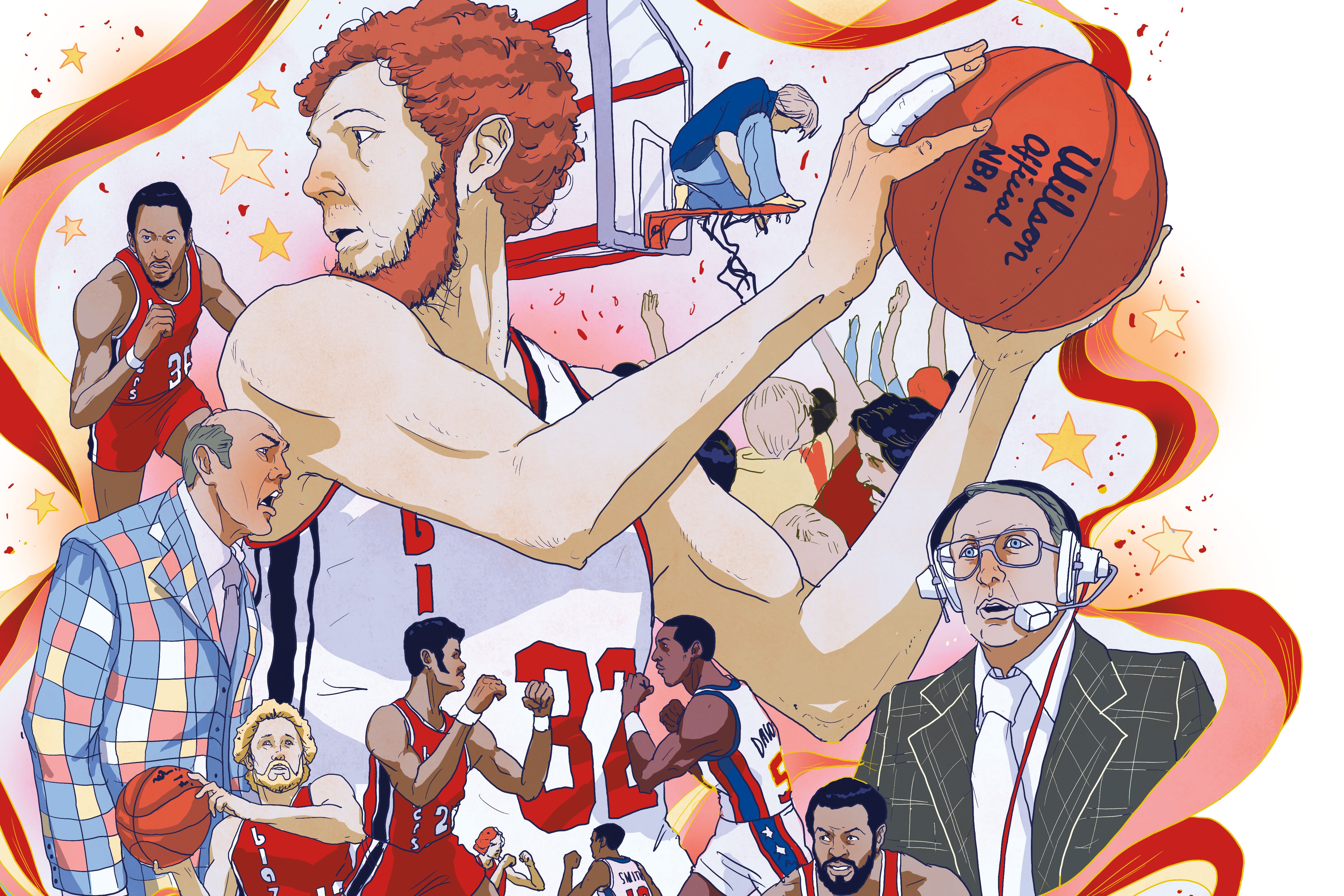

The NBA Finals do not start well for the Portland Trail Blazers. As the first game in the best-of-seven series begins, Bill Walton, the team’s hulking, red-bearded center and talisman, faces up against Philadelphia’s Caldwell Jones at center court. Both men spring into action too early, before the ref tosses the ball for tip-off. “You can just see the anxiety,” CBS announcer Brent Musburger says.

Seconds later, Philadelphia’s great Julius Erving—Dr. J—throws down one of his marquee dunks, sailing to the basket with a thunderous finish. The Spectrum crowd roars. Yet the Blazers hang around, buoyed by Walton’s 28-point, 20-rebound performance, until the fourth quarter, when three key Portland starters foul out. By the final buzzer, Sixers fans swarm the court. “All season long I have wondered about the blasé crowds here in Philadelphia,” Musburger says. “Not today.”

They weren’t blasé in Portland, either.

Today, echoes still resonate from the frenzy—Blazermania—that swept the city 40 years ago. Photographs. Framed newspaper articles. One warehouse-size Blazer-themed bar, called Spirit of ’77. When Oregon’s first major-league team battled the Philadelphia 76ers for the NBA championship, the attention proved intoxicating. The series brought Portland to sporting prominence for the first time; in many minds, the city and its team became inseparable. For those who lived through 1977—perhaps especially the players—they still are.

Bobby Gross could be any customer at Stanich’s, the pennant-lined burger bar at NE Fremont and 49th. A man in an Oregon Ducks sweatshirt flashes him a knowing look. Gross squints: a familiar face? He smiles back vaguely and takes a seat.

In 1975, the Trail Blazers made the Long Beach State player the 25th pick in the NBA draft. “I didn’t even know until the next day,” the 63-year-old recalls, slouching back in his chair. “There was a press conference about a week later. I got into town and hopped in a taxi. Nobody met me at the hotel. The press conference lasted about five minutes, and there were probably three or four reporters there.”

The Blazers practiced at the Jewish Community Center in Southwest Portland. The rookie looked around. “There were a lot of good players on that team,” he says. “I remember asking Barry Clemens, ‘How many games do you think we can win?’ And he says, ‘Well, probably 30.’ Thirty games!” (NBA teams, then and now, play 82 regular-season games.)

Injuries and chemistry issues took their toll in ’75–76. The coach, Lenny Wilkens, was only a year past being a player himself. “He gave us a 15-minute speech, and then just threw the ball out and let us start scrimmaging,” Gross says. “That was it.” The Blazers won 37 games.

Dr. Jack Ramsay, a veteran college and NBA coach, replaced Wilkens for the ’76–77 season. Injuries—including Bill Walton’s—healed, and the Blazers won 49 games before burning their way through the playoffs. Gross became Walton’s favorite passing target and—in the finals—the man responsible for neutralizing Dr. J. “The intent was to make sure he would guard me,” Gross says. “And the only way to do that is if I’m scoring.” Dr. J, one of the greatest NBA players of all time, would prove a tough assignment.

Your 1976–77 Portland Trail Blazers: (standing, from left) Lloyd Neal, Larry Steele, Corky Calhoun, Bill Walton, Maurice Lucas, Wally Walker, Robin Jones, Bobby Gross, (seated) Herm Gilliam, Dave Twardzik, Johnny Davis, and Lionel Hollins, with coach Jack Ramsay next to Hollins

Game Two: Philadelphia / May 26, 1977

Julius Erving puts on a first-half show: heart-stopping dunks, a brilliant midcourt steal, circus layups. Sharp elbows and rugged screens fly on both ends of the court. By halftime, the Sixers lead by 18.

In the fourth quarter, tensions mount. “They’ve gotta get on top of these fouls,” commentator Rick Barry says as Philly’s George McGinnis and Blazer Lloyd Neal begin pushing each other. “They can’t allow this to happen.” With five minutes left and the 76ers up 20, Philly’s Darryl Dawkins wraps up Gross under the basket, then throws him to the ground. They exchange words. Dawkins goes after Gross, swinging at him but striking a teammate instead. As Dawkins backs away, the Blazers’ Maurice Lucas smacks him with a forearm to the back of the head, and they square off. Lucas shadowboxes Dawkins before teammates and police drag them apart. The Sixers win by 18 as the game ends on a strange, charged note.

Mike Dunleavy, now coach at Tulane University in New Orleans, was a rookie for Philadelphia in 1977. He recalls the fight well. “I remember running off the bench, and Henry Bibby grabbing me from behind and saying, ‘Where you goin’, rook?’ he says. ‘We don’t get into the fight until that guy gets into the fight.’ And Doc (Julius Erving) was sitting at half court with his legs crossed. Bibby says, ‘When he’s in it, we’re in it.’”

“We had some internal debate about it with Darryl Dawkins,” Dunleavy says. “I think he felt that people didn’t have his back. It took away from our focus a little bit. We kind of brushed it off, like, ‘Yeah, no big deal.’ The Blazers took it as something to rally around.”

“The fight did kind of light a little bit of a fire under us,” says former Blazer guard Dave Twardzik, who still exudes an aw-shucks, boyish charm at 66. “It might have been destructive to the Philly psyche and locker room.”

The series returned to Portland. Before game three, Lucas pulled a move that looms large in the 1977 mythos. In today’s NBA, opponents often shake hands and hug before games. In 1977, stricter battle lines were drawn. Lucas broke them. “Lucas went down after the introductions, and shook hands with the opposition,” remembers Bill Schonely, who spent decades as the Blazers’ iconic play-by-play announcer. “Bingo—turning point of the series.”

Lucas, who died in 2010, acknowledged that the move was calculated. “After that, [Dawkins] was done,” he later told the Oregonian. “One of the smartest things I ever did.” (Dawkins died in 2015.)

Gross remembers another factor, too: “We came back after losing two, and we couldn’t get through the airport because there were too many people there. That’s when we knew we had something special with the fans, and they had something special with us.”

Game Three: Portland / May 29, 1977

Blazers fans squeal like Beatles-spotting teenagers and bound out of their seats whenever Portland gets to the rim. The team rewards them with fast breaks and 24 points in the game’s first eight minutes. Walton directs traffic as the Blazers outpass and outrun the visitors.

“I think all of us wondered what might happen in this series after those first two games at Philadelphia,” Musburger says with just over a minute left before the Blazers claim their first victory of the series. “There’s no wondering now: this is going to be a marvelous showdown.”

If Philadelphia has perpetually ornery home fans, the Blazers have Rip City.

Strange that a place called Memorial Coliseum would, itself, erase history. The development of the Blazers’ original home arena razed an entire neighborhood, McMillen’s Addition. On its 1960 completion, 500 homes, half of them occupied by black Portlanders, had been destroyed.

Harry Glickman remembers McMillen’s Addition. “Great jazz clubs,” the 93-year-old says wistfully over sandwiches at the Multnomah Athletic Club, where he’s been a member since the early 1960s. Back then, he was one of a handful of Jews admitted to the venerable hub of Portland high society, a fringe benefit of promoting NFL exhibition games at the stadium next door.

Glickman: a veteran who never really took to military life, a journalist who became promoter, and a self-described liberal who says that in the ’70s, Portland was “conservative in every way: education, entertainment, manufacturing—the whole nine yards.” His features have grown outsize with age; his health in recent years has been uneven. But his voice remains strong and impossibly deep, and his memory as sharp as his biting sense of humor. Raised by immigrant parents in Depression-era Portland, Glickman thrived on bold gambles; he uses the words “hustle” and “scheme” with affection. He brought boxing matches and exhibition NFL games to the area, then ran a minor-league hockey team, the Portland Buckaroos.

Starting in roughly 1955, Glickman pursued a franchise in the up-and-coming National Basketball Association. It was a tough sell. “I’d go to Madison Square Garden to meet with [Knicks cofounder] Ned Irish,” Glickman says. “His great comment was, ‘How am I going to put the name "Portland" on the marquee at Madison Square Garden?’ The question today is, ‘How are you going to put the name "New York Knicks" on the marquee at the Moda Center?’” Finally, the league granted Portland a franchise on Febraury 6, 1970.

In his blunt 1978 autobiography, Promoter Ain’t a Dirty Word (“not a best seller,” he quips now), Glickman delights in the details of bringing a team to life. “As a compiler of lists—if I don’t write it down I’ll forget it—I had identified 300 things to be done prior to the college draft six weeks later,” he writes. The list included “everything from selecting a name for the new team to choosing the colors for our uniforms.”

One of Glickman’s sharpest decisions was hiring Bill Schonely, the announcer who became a local legend for catch phrases like “Red hot and rolling!” and the enduring “Rip City!”

“Harry called me up, and he said in his big, bass voice, ‘How would you like to do NBA basketball?’” Schonely remembers, sitting courtside at today’s Moda Center. (At 88, Schonely often attends Blazers home games.) “I sat in his office on Multnomah. We talked for five or six minutes and that was that. That was 47 years ago.”

Schonely’s mission: evangelize. “I said, just go around the state and make friends,” Glickman remembers. “So he’d go and talk to the Lions Club on Wednesday and the Rotary Club on Thursday. Then he’d play golf with a station manager.”

“I went to the Astorias, the Lincoln Cities,” Schonely says. “I went down on bended knee to ask stations to carry NBA basketball. A lot were hesitant, because it was so new. My basic pitch was: Portland’s in the big leagues, Oregon’s in the big leagues, and you’re going to be a part of it. And they’d say, ‘Well, all right, Schonz, that doesn’t seem too bad.’”

Game Four: Portland / May 31, 1977

Early, the Blazers lead 17–4. Ramsay wears a tan, open-collared suit jacket more appropriate for a safari than a basketball game as he stalks the sidelines. Philly’s coach, Gene Shue, picks up a quick a technical foul for screaming at the ref.

They call Maurice Lucas an enforcer for flattening opposing players. Today, he picks up the offensive slack for Walton, who has an overwhelming scoring game but thrives as a shot blocker. “This Portland team is really inspired,” Barry says. “They’re playing almost picture-perfect basketball.”

The Sixers rally before halftime, behind another great Dr. J performance, but the Blazers execute smooth, pass-first basketball in the third quarter. Blazer rookie Johnny Davis makes thrilling drives to the basket that draw fouls to become three-point plays. Barry calls it a “total breakdown” by the 76ers. The Blazers win by 32. Point guard Lionel Hollins is calm and steady throughout.

Hollins didn’t immediately take to Portland. “I flew in, it was just clouds. I came out of the clouds, and into the mist,” he says in a dark, windowless den off the lobby of the Nines Hotel. “I was by myself. I was young. I was here for about two weeks, and it rained every day. I mean, I grew up in Las Vegas. I went to school at Arizona State. So I got back on a plane and went home.” This was 1975, the same year Bobby Gross was drafted.

Hollins would begin his pro career a young black man in the whitest city in the NBA, but he says now that he seldom encountered racial static. “Portland was actually better than Vegas,” he recalls. “Vegas was oppression to the highest degree. We couldn’t go to the Strip or stay at hotels—none of that stuff. We had our own black downtown. So coming to Portland was totally a different environment.”

Instead, he says his first two seasons were exercises in being ignored. “You’ve got to understand, there wasn’t Blazermania until we got into the playoffs,” he says. “Nobody knew who I was, and most people didn’t even care about the Blazers.”

Maurice Lucas drives to the basket.

Game Five: Philadelphia / June 3, 1977

The return to Philadelphia is scrappy from the start, with Portland’s guards—especially rookie Johnny Davis—wreaking havoc. But it’s Walton, screaming out plays and skying for rebounds, who sets the tone. A bearded figure with a counterculture vibe, he waves his hands above his head in patterns that suggest a twirler at a Grateful Dead show. He also shuts down the Sixers.

“I have never seen a man start any better on defense than Walton has in this game,” Musburger says. The Philadelphia crowd is reduced to uneasy applause and gasps.

Late in the game, a CBS camera catches Coach Shue addressing his Sixers, down nine. “It’s a quick play—quick play,” he says. “You don’t have time to be fucking around with the ball.” Too late. The Blazer defense persists; Philly fans begin booing as the clock winds down. “You’re still the worst!” one fan yells.

The strangely mesmerizing 1978 film Fast Break opens with shimmering blue water in some rural corner of Oregon. Over mellow acoustic guitar, a shy voice muses. “Basketball is ... is part of living, you know, and almost everything that works in basketball is—you know, has that same, uh, counterpart, in your life away from basketball.”

A lanky, sunburnt male body in short shorts and a yellow tank top enters the frame. He sports a shaggy head of orange curly hair, his arms and legs folded like origami on a rock by the lakeside. He speaks slowly. “The same tricks work,” the young philosopher says. “And when you mess up, they call a foul on you.”

This was Bill Walton, enigmatic center for the Portland Trail Blazers, source of much of the lore that evolved around that team. His time here proved brief and mercurial. Off the court he could be controversial—his politics were radical, he was a vegetarian. An urban legend (sadly untrue) involves Walton smuggling Patty Hearst across the country. On the court, though, Walton was every teammate’s dream: an unstoppable seven-footer (he’d claim to be six-foot-11) willing to share both the ball and success.

“If you talk to people who have been around the league,” Schonely says, “they’ll tell you that if Bill Walton would have been healthy for a longer period, he might have gone down as the best center ever.”

“Between that season and the next, it was probably the greatest stretch of a center that I ever saw play,” Dunleavy says. “He did virtually everything.”

Walton himself, speaking from his home in Southern California, tends to disagree. When asked how much credit he deserves for the ’77 Blazers, he answers quickly.

“None,” he says. “I was just lucky to be there.”

Pressed, he concedes the remote possibility of helping his squad succeed. “You never know what makes a team work,” Walton offers. “But you know what makes a team fail, and it’s always the same: lack of honor, selfishness, and greed, which leads to hate and anger.”

Whether Walton admits it or not, he led that team to glory—even if he didn’t look ready at the start of ’76–77. “He came in way overweight,” Gross remembers. “I’m sure he’d heard that he needed to put some bulk on. So he put on about 30 pounds of fat. He said he did it by drinking beer.”

These guys were kids. Walton picked out Hollins’s first bicycle, and the two went hiking with a Dead roadie called Ramrod. They swam at Sauvie Island. Walton enshrined himself forever in Portland’s heart by riding his bike from his home in Northwest to the coliseum for games.

“I just assumed that every place in the world was like San Diego,” Walton says. “We lived outside in San Diego. Often I’d even sleep outside.”

Yet when Walton talks about the Blazers, his voice shakes. Injuries warped both his NBA career and his retirement, even though, today, he is one of televised basketball’s best-known voices. Walton has undergone almost 40 orthopedic surgeries, including procedures for broken leg, foot, and wrist as a young Blazer, and spinal and ankle fusion surgeries after retirement. He told Sports Illustrated last year that he considered suicide after his latest back surgery. “When you spend half your life in the hospital,” he says, “and you spend years on the ground wishing you were dead, because it’s just too much pain and you can’t move and you can’t think and you can’t dream and you can’t function? That’s when you learn things.”

“That was my team,” he adds, of the ’77 squad. “That was my life, that was my world. And I lost it. And it was awful.”

Dave Twardzik passes in mid-air.

Game Six: Portland / June 5, 1977

Walton anchors the Blazer defense. His body contorts as if in a funhouse mirror as he clings to rebounds, then fires the ball to distant teammates. The guards—particularly Lucas and Davis—repay Walton by cutting at speed. But the 76ers don’t relent, and Dr. J (who will score 40) is both the team’s best player and its loudest cheerleader. At first quarter's end, Musburger fawns. “We’ve got one cooking where both teams are playing well,” he says. “It can’t get any better than what we’ve seen so far.”

By the third quarter, the Blazers lead by 12, and a frisson runs through Memorial Coliseum. After a timeout, the camera pans to a front-row fan in a hand-decorated Blazers shirt that reads, in red and black, “JUNE 5, 1977 – BLAZERS WIN NBA TITLE!”

With five seconds left and the 76ers down by just two points, 109–107, the crowd seems stunned. So does Rick Barry: “If they take the ball inbounds right now, George McGinnis is wide open! I don’t know what they’re doing!” The 76ers indeed pass it to McGinnis, who takes an uncontested shot. But McGinnis’s jumper hits the front of the rim. Dr. J’s attempt at a rebound deflects to Davis, who jets to center court as time runs out.

A beat of disbelief, then fans flood the court in a chaotic scene. “It’s over! It’s over!” Musburger yells. Walton, his mouth open and his head slouched with exhaustion, makes his way through a sea of back-slapping hands. His jersey has vanished. He is swallowed up. In a move that will incense Blazer fans for decades, CBS forgoes postgame interviews and celebrations to cut to coverage of the Kemper Open, a golf tournament.

The Blazers, of course, have yet to win a second title. But Blazermania survives. In good years and bad, the Moda Center—the current name for the team’s larger home, completed in 1995—remains a rare, unifying rallying point for a fan base spread from Battle Ground to Klamath Falls. The Blazers are something Northeast Portland shares with Oregon City, a common point of pride for working-class Gresham and hip Sunnyside. Fandom is an unquestioned right for natives and transplants alike.

“I think for this particular group of players, an eclectic group, Portland was perfect,” says Johnny Davis. “We had all these different things that we were doing in our personal lives, but when it came to representing the Trail Blazers, we were all one. We lived that way, we practiced that way, and we came to know each other that way.”

“There was a void to be filled,” Hollins says. “And we stepped into it, and people started rallying around us. The love affair began at that point, and it continued.”

In the summer just after the championship, Walton rode his bike to the Oregon Coast with Larry Colton, a Portland writer who penned a freewheeling book about the Blazers in 1978. “That ride was a total freak show,” Colton remembers now. “He was the most renowned athlete in the world, basically—especially in Oregon. So we’re going down 101, and cars are practically driving off the road when they’d see him. ‘Was that Bill Walton?’ Guys on bikes going the other direction would turn around and ride with us for a while, Winnebagos would pull over to talk to him. He got pulled over in Lincoln City, and the cop let him go.”

“Blazermania was and it is special,” Walton says, ramping up the stream-of-consciousness riffage for which he has become known. “We didn’t know at the time. When you’re setting all these records and playing some of the greatest basketball that’s ever been played, and these fans are pushing you and they’re coming with their signs, and they’re putting gifts of love and offerings of love and peace on your front porch before you even get up, and they’re standing on the streets of Portland as I’d ride my bike from Northwest Portland to Memorial Coliseum, and they’re cheering, ‘Go Blazers Go,’ and Bill Schonely calls the game and he announces what the flight schedule is and 25,000 people show up at the airport—” his voice quivers “—at the airport! The airport became nonfunctioning because these fans come and they say, ‘We believe! Let’s go, we can do this together!’ Are you kidding me? That was the greatest thing in the world.”

Listen to Bill Walton recount his time with the Trail Blazers in an interview with writer Casey Jarman (audio quality is rough).

For Gross, who never left Portland, the championship felt like the first of many. “I was thinking to myself, this is a young team, we’re going to do this again multiple times,” he says. “I’ll take it the way it came, but I wish I would have won a championship later in my career.”

The next season, Gross broke his leg. He’d retire in 1983, before his 30th birthday. “When I was playing, the only dreams I ever had were basketball dreams,” he says. “It took me a couple of years after I was done for that to go away. When you’re young, you have those strange dreams about school? I’d have strange ones about basketball. About being hurt and coming back—about being wanted by a club. I don’t know why you go back to those places.”

Winning also fostered a hunger for more. Bill Walton kept returning to the basketball court, even when his body tried to tell him to stop. He would win another championship late in his career, with the Boston Celtics, but he says it’s playing with the Blazers he remembers.

“I wish it had lasted—you always wish all the great things had lasted longer,” Walton says now. But for him, and for longtime Blazer fans, the championship is something more than just a memory. It is legend—one that helps bind Portland together.

“This happens all the time to me,” Walton says. “I’ll be somewhere. I’m a busy guy, I keep a full schedule and I’m on the go. People come up to me and say, ‘Bill, I loved you at UCLA,’ or ‘I saw you at a Grateful Dead show,’ ‘I saw you give a speech,’ whatever. But then these folks come up to me—often enough that I can see it coming now, because they have a dazed but very focused look in their eyes—and they come right up to me face to face, and they look at me and they say, ‘I was there.’ If you were there, you know how special it was, how perfect it was, how glorious it was.”