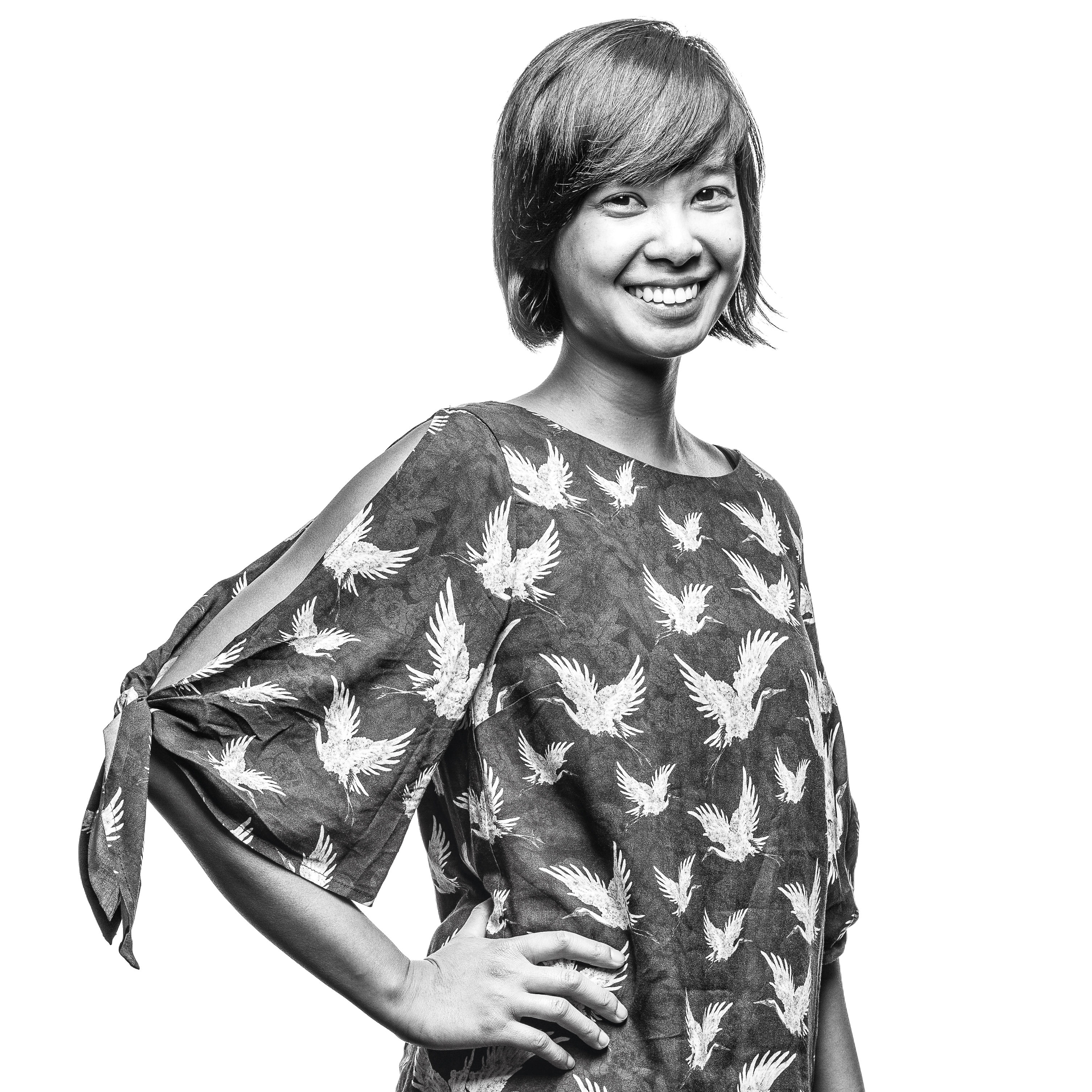

At Tender Table, Women and Nonbinary People of Color Share Stories of Food and Family

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

To poet Stacey Tran, a bowl of noodles is rarely, if ever, just a bowl of noodles: they’re a trip down memory lane, a writing prompt, and an invitation to talk about the intense crossroads of food, identity, and culture. For the past year, the Beaverton native, whose family emigrated from Vietnam in the 1980s, has hosted Tender Table—a warm, revealing storytelling series in which local women and nonbinary people of color tell stories about food and family, complete with tastes of dishes that mean so much to them. A local photographer might share the Filipino tradition of pasalubong, a writer dig into body image or cultural appropriation in food; Tran’s own mom has presented. With a Regional Arts & Culture Council grant and ambitions for a traveling Tender series, Tran is set to only bring more to the table in years to come.

My parents and I spoke Vietnamese to each other while I was growing up. After day one in preschool I came home rattling off English, and my mom was like, “Oh no, no. No English.” It was her way of immersing me in the language. I think that was really cool. In the car, she’d tell me to write down her grocery list in Vietnamese to practice writing. I’d get things wrong [I’d switch words for xương (bone), sườn (pork ribs) and xuân (springtime)] and she’d make fun of me, but she explained that that’s how I’d remember next time. Now, my fiancé is an English speaker, so when we’re together my parents will speak in English. But Vietnamese is our heart language.

I felt the need to bring people together around food and stories about food. So much of my own upbringing centered around the dinner table. I’ve heard a lot of stories about my parents’ time in Vietnam (they came here in the 1980s in their 20s). A lot of it was translated through the food they were sharing with me. Or the lack of certain ingredients they were only able to find in Vietnam. As a kid, we spent summers in Vancouver, British Columbia, so my mom could stock up on Asian dry goods and really pleasant tropical fruits that don’t grow here—rambutan, dragonfruit, custard apple (now they’re commonly sold in Asian markets or even Fred Meyer).

Just thinking about a rambutan … there’s an act of care and service that’s involved with how my mother would cut it open a certain way, and give it to me in a certain way, and give me instructions on how to eat it. There’s a lot of dignity and pride in raising our children to know how to eat the food you ate when you were growing up. All those very tangible memories are connected to just that one piece of fruit. When ingredients come together and make [a dish] think of all the memories infused in that.

I never thought that something so sentimental as food and story would bring so many people in. It’s fantastic. I seek people out based on their interest in telling their stories about the food they grew up with and the food that they make to claim their sense of culture and identity. A lot of people coming are femmes of color who see themselves in the series, as well as people who are just interested. There’s a lot of—not nostalgia, but looking back and examining a past, whether that’s childhood or ancestral or beyond. The thread through all of it is memory. There’s no veneer to how the stories are presented. Oftentimes I leave feeling very raw and vulnerable.

A lot of Portland restaurants serve “ethnic” dishes. To be quite frank: white chefs selling food from other cultures without really investigating where these foods come from is very problematic. Lots of places in town do that. And there are places that are respectful, and do embrace the culture that they are learning from, and give credit. If I said that I’m not going to any restaurant owned by a white person who cooks ethnic food, I’d be a hypocrite. But there’s a need to claim, reclaim, and establish awareness—say, what is bánh mi, and what it actually means. Or how kale is now a superfood but once it was a slave food. Tender Table is a place where those conversations happen.

There’s a way of doing things—rituals—to show people around you that you are part of a community. When my fiancé and I were just dating there were a lot of things that he did to show my parents that he was serious [about the relationship]; to show that he was able to eat, to show that he’s committed to being part of the family. There’s a really strong, pungent sauce called mắm nêm that you eat with a certain kind of salad roll or fish. It’s intense, even many Vietnamese people don’t partake. But Jack really likes it, and it impressed my uncle that he eats it. It’s a little inside baseball.

My mom’s food is really good. (My dad’s food is really good, too.) Have you had bún bò huê', a spicy Vietnamese noodle soup? I will never be able to be vegetarian because I love that dish so much. I eat it with my mom once or twice a year—it’s a big effort. She makes a broth, and there’s ham hock and blood cake, and she uses morning glory stalk for garnish.... She has a whole garden of herbs at home. (That’s the thing with Vietnamese food—you have to have all the herbs.) And she makes a killer chile oil. I think of her making the noodles, and when we come over she tells us to put the noodles in the bowl and heat them up in the microwave so that they don’t cool down the broth. It’s a labor of love.

Hànôi Kitchen does serve a pretty complete bowl of bún bo huê—the broth is pretty close. I mean, I can see my mom eating it … and saying, “This isn’t as good as mine.” But what can you do when you can’t knock on your mom’s door?

Stacey Tran’s first full-length book, Soap for the Dogs, debuts March 1. Find a full schedule of upcoming Tender Table events at tendertable.com.