COVID-19 Is Finally Waning. Can Portland Let It Go?

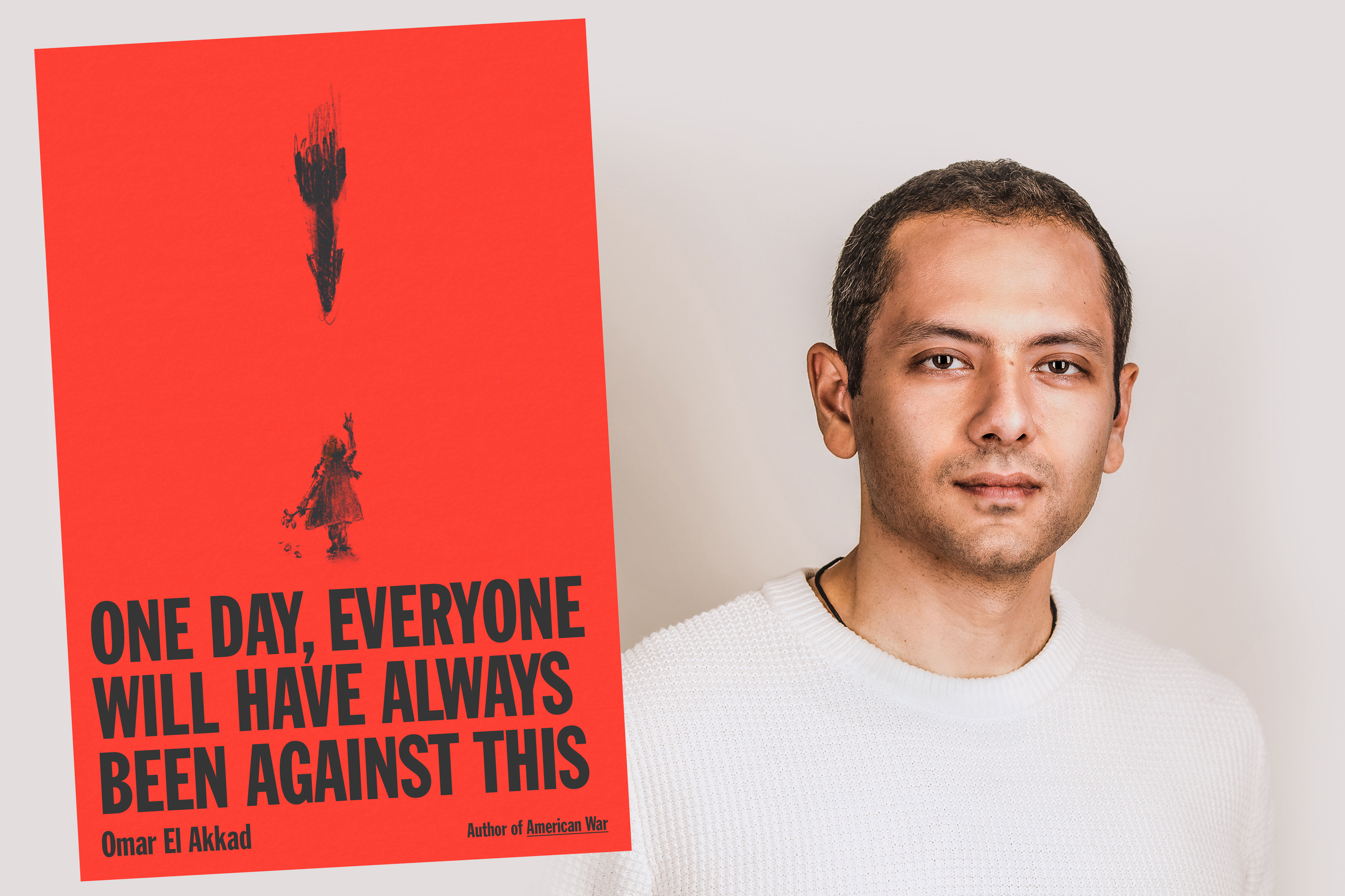

Above illustration by Chris Danger

With summer on the horizon, Portlanders should have plenty to celebrate. The sun will make its annual guest appearance in our oft-soggy skies, any adult who wants a COVID-19 vaccine will be able to get one, and—so far—we’ve made it through 18 months of this pandemic without overflowing our hospitals and with per capita case count rates that are the envy of 48 other states, though we collectively mourn the more than 2,500 Oregonians who’ve died after contracting the virus.

And yet, even as much of the rest of the country is looking ahead to vaccine-propelled summer fun—airline bookings are way up, Shakespeare in the Park is back in New York City, and Disney is open in both Land and World—plenty of Portlanders, even the fully vaccinated ones, are reluctant to relax.

Signature summer events, including Sunday Parkways and the Rose Festival that take place mainly outdoors—where the risk of transmission is extremely low—are staying virtual or scaling way back for the second year in a row. Superintendents say they “expect and intend” that kids will be back in school full time this fall but offer no guarantees. And despite the CDC’s blessing to ease up on outdoor mask use even for the unvaccinated who are out for a walk with family or a solo jog, many Portlanders are still giving a wide berth or the stinkeye when they spot a bare chin coming down the street.

In other words: somewhere along the way, COVID Zeroism set in around here. The term, as defined by writer Jonathan Chait in New York Magazine, means “an inability to conceive of public-health measures in cost-benefit terms, [in which] the pandemic becomes an enemy that must be destroyed at all costs, and any compromise could lead to death and is therefore unacceptable.” According to this philosophy, the prepandemic world can only really return when risk falls all the way to zero—and if it never gets there, then we’re never going back to unmasked hugs, beers in bars with strangers at our shoulder, and full-time school.

Portland’s attitudes toward the pandemic and subsequent public health restrictions can be traced back to the one man that many in the city would be just as happy to forget: former President Donald J. Trump, who downplayed the virus at every possible turn. (Remember when we were all supposed to pack into church for Easter … in 2020?) As in many progressive enclaves, Portlanders recoiled from Trump’s recklessness alongside the prudent public health professionals setting our policies.

“My observation is that [the former president’s messaging] pushed people further to extremes, including liberal Democrats,” says pollster John Horvick, the director of political research at Portland firm DHM Research. A Texas-style “last maskless person to the bar is a rotten egg” message wouldn’t fly in Oregon, Horvick says, but the rightful rejection of COVID deniers crowded out more nuanced takes, too, particularly on low-risk outdoor gatherings. (A review of studies on transmission published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases found that the virus was roughly 20 times more likely to spread indoors than outside.)

Public health projections and messaging in Oregon have been on the extremely risk-averse side, (even though the state has periodically allowed indoor dining to resume at reduced capacity, a much chancier activity than, say, an outdoor block party, for which permits in Portland are still on pause.) Peter Graven, a health economist at OHSU whose forecasts have been central to Gov. Kate Brown’s decisions on when to order past lockdowns and freezes, mapped out a scary February–March 2021 spike in cases that never materialized. Instead, case numbers, hospitalizations and deaths slid dramatically between January and early March before ticking back up.

Graven then pivoted to projecting a big 2021 spring-summer spike, estimating that the state would see a peak of 1,210 new COVID cases per day by May 4, driven by fast-moving variants. So far, his direst forecasts haven’t born out: the actual May 4 case count was 748; the spring peak so far topped out at 1,002 cases on April 22. And though hospitalizations did climb in Oregon in April, that rate of growth has slowed considerably—enough that Gov. Kate Brown on Tuesday eased up on a lockdown she’d put in place less than a week ago, reopening the door to limited indoor dining, gyms and live fans in sports arenas.

Still, Graven’s influential forecasts remain grim. Despite the recent positive trends, Graven argues, Oregon hasn’t seen the end of strained hospital capacity; most recently, he projected that the state could see 473 hospitalized people by late May, close to the worst of the pandemic back in November and December. In his projections, Oregon is not expected to have negligible COVID-19 related hospitalizations until August—several months past the point at which adult vaccination rollout is expected to be complete and despite CDC findings that the vaccines also curb transmission. (Meanwhile, forecasts from elsewhere, including the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, have been considerably more bullish on Oregon’s likely trajectory over the next few weeks. And on May 5, the CDC released new models for the summer, the most optimistic of which showed the pandemic as "under control" nationwide by mid-summer.)

But the epidemiologists advising Brown on state policy have matched Graven's cautious tone. Despite the updated CDC guidance, they’ve yet to relax any state guidelines on wearing masks outdoors, citing the variants that shut down Europe this spring, along with the unknown of how long immunity from vaccines will last, (though early research on the Pfizer vaccine shows it remains extremely effective at preventing severe disease even after six months, and likely longer).

“If you are walking by someone outdoors or on the street, and you don’t have much space to get away from them as you pass, you have no idea if a stranger walking past you is vaccinated or not,” says Thomas Jeanne, the deputy state epidemiologist. “In the grand scheme of things, it is a low risk passing someone within six feet, but you never know. Maybe they are going to cough right before they pass you. So until we get to a majority of people vaccinated or beyond, it is hard to say that in public people don’t need to wear masks.”

It's indisputable that the pandemic has taken real tolls and that precautionary measures are necessary to guard against spread. In addition to the more than 2,500 people who have died in the state, around 187,000 Oregonians and counting have contracted the virus.

But there’s also the collateral damage to weigh: the unemployment rate is stuck at around 6 percent, and is particularly acute in the battered hospitality and leisure sector, which lost more than 110,000 jobs last spring. Experts at Stanford’s Children’s Health Center are pinpointing increases in both childhood obesity and eating disorders, while economists at Yale say students from the poorest communities can expect to earn at least 25 percent less over the course of their lifetime due to prolonged school building closures, even as the same study found no corresponding losses for the wealthiest 20 percent of students.

In Oregon, though, the messaging around safety and the dire risks of COVID-19 has taken precedence above all else. Horvick says he floated the idea of an Oregon Health Authority campaign that sang the praises of vaccines, dangling incentives like being able to attend a high school graduation or hug a grandkid as a reason to get a shot. “We needed and still need things to look forward to, to motivate us to take these public health steps,” he says. (President Joe Biden, at least, may have been listening: He’s promised Americans we can have Fourth of July barbecues with friends and family, assuming the vaccine rollout continues apace.)

In Oregon, carrots like these didn’t fly, given fears that if given an inch, the state’s cooped-up residents might take a mile. Instead, the messaging around what’s safe to do outside has remained the same since March 2020, though OHA officials point to a recent rollback of masking rules for youth non-contact sports outdoors as a possible hint at their future direction. (The move came only after a high school track athlete in Bend collapsed at the finish line of a race.)

And there is fallout from the red-alert vigilance: Portland Parks and Recreation isn’t holding outdoor free concerts or movies in the park this summer and won’t offer open swim for the second year in a row—effectively blocking a chance to cool down for those with no access to private pools. The rules are also why organizers for the Rose Festival, Portland’s historical summer kickoff, decided to scale back their event, including doing away with the traditional parades. (Some larger paid events will go forward, however: as of now, 6,300 people will be allowed to cheer on the Timbers and the Thorns at games, or 25 percent of the outdoor stadium’s full capacity.)

“Events are possible, but still very questionable in the next few months,” says Jeff Curtis, the CEO of the 114-year-old Rose Festival. “We did consider scaled-back versions, all options. But at the end of the day, the uncertainty about what is possible remains.”

What Portland and Oregon really lack is any prominent and influential public health specialist or politician publicly making the case for data-driven, pragmatic risk tolerance to factor into policy decisions on outdoor events in particular. (One exception: Last summer’s protests in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, which drew thousands of people to downtown Portland at its peak. Mask-wearing, but not distancing, was prevalent, and Multnomah County health officials have said there were no outbreaks linked to the events.)

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, a consortium of researchers from Harvard, Tufts, and MIT campaigned for months for open public schools; this spring, the state’s governor ordered all public schools to open full-time, five days a week. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio ordered 80,000 city employees to return to their offices by early May, citing the need to “send a powerful message about the city moving forward.” And in Texas, officials are forging ahead with plans for the annual Texas State Fair, after the deep red state vastly loosened restrictions this spring, and, with an aggressive vaccination campaign open to all over 16 since the end of March, saw its case numbers and deaths continue to plummet.

It’s all a very different message than the one that prevails here, and some are left wondering why.

“I don’t think Oregonians are able to assess risk appropriately at this point,” says Michele Babaie, a Portland-based internal medicine specialist, who has advocated for school buildings to reopen. “COVID is serious, but life is risky. Being outdoors, distanced, in a city with such low numbers, that’s extremely low risk. It’s probably riskier driving to the event than being there.”