Is This the Portland Commuter River Ferry the Prophecy Foretold?

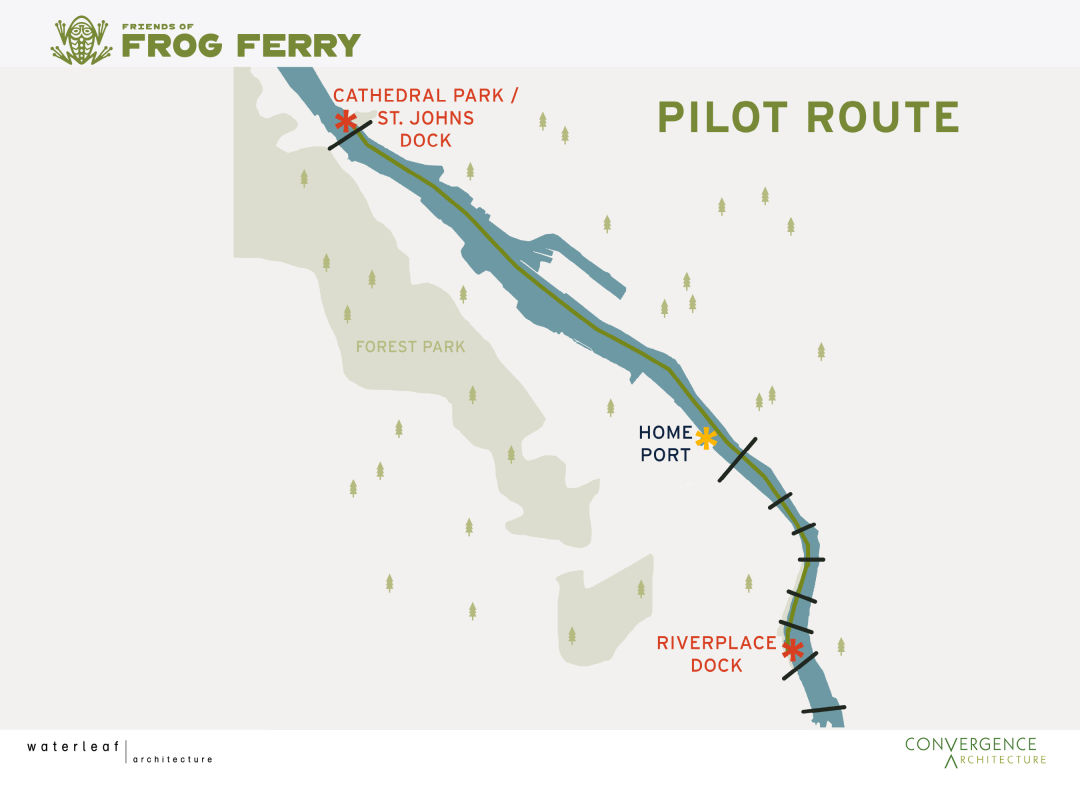

The proposed route for the info-gathering pilot stage of Frog Ferry

It was in the gym hot tub that James Paulson first started thinking about a Portland river ferry, he told a crowd gathered in Cathedral Park Tuesday for the launch of Phase 2 of the Frog Ferry project.

Paulson, a local property manager who now chairs the Friends of Frog Ferry board, certainly wasn’t the first. The idea pops up every decade or so in hot tub musings, in shower thoughts, in business meetings, in government retreats. There are conversations, like the one Paulson soon had at happy hour with Susan Bladholm, who founded the Friends of Frog Ferry nonprofit. There are studies, like Frog Ferry’s Operational Feasibility Study and Finance Plan. There are proposed routes and stops and schedules to whisk happy commuters and sightseers up and down the Willamette. Then financial and logistical reality sets in, and the plan is shelved.

But this time will be different, Frog Ferry’s boosters say. Bladholm, a former Cycle Oregon director who worked for the Port of Portland and Erickson helicopters, called ferry service “a proven, low-cost, educational transit mode” in her remarks at the Cathedral Park press event. She seized on the language of equity and access, envisioning “a Portland where everyone has the opportunity to get out on the river and leave their cars behind.” During the pilot phase, one-way tickets would cost $3, or $2 for honored citizens. The intent is to keep prices low and let kids ride free. Ultimately, the pilot phase is meant to evolve into a seven-vessel, nine-stop transit system that would cost $40 million to reach full operation. Frog Ferry reps say they want to integrate with TriMet and its Hop cards, and with Biketown, the short-term bike rental service that doesn’t currently serve St. Johns.

Sam Adams (on stage, from left), Susan Bladholm, and James Paulson in Cathedral Park on June 8

“This has been a good idea for a long time,” said another speaker at the press event, Sam Adams, former Portland mayor and the director of strategic innovations for current mayor Ted Wheeler. “But this is now doable.” After what Adams called one of the hardest years in the city’s history, it’s also “the kind of project we need to be moving forward on.”

And moving forward they are, lining up $9 million for the three-year pilot phase, with a year or so of planning starting now and then two years of ferry service between St. Johns and RiverPlace. The City of Portland is applying for $3.3 million in federal funding, and Bellingham shipyard All American Marine is drawing up plans for custom boats that could fit under our low bridges. The vessels will start with a diesel propulsion system, but the intent is to switch them to electric operation. They’d fit 70 to 100 passengers, with room for up to 12 bikes in the aft section.

All American Marine’s rendering of a potential Frog Ferry vessel

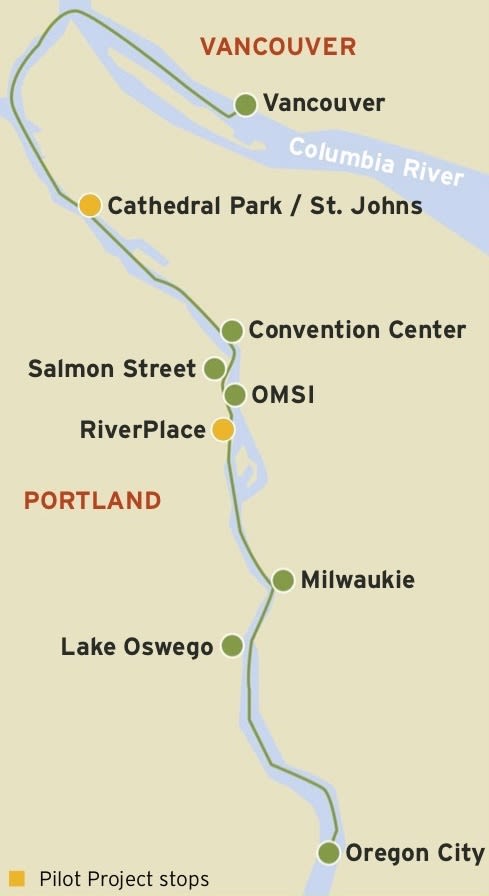

Maybe the pilot project will turn into a permanent transit option from Vancouver to Oregon City. Maybe local schoolchildren will soon be invited to name the vessels. (Hey, kids, wouldn’t Boaty McBoatface and Bryan Ferry be great names? No? Ugh, kids today!) Or maybe, once again, nothing will happen. But here are five reasons why Frog Ferry just might get past the hot tub musing/barstool brainstorm stage and take form.

1. Traffic keeps getting worse, and transit is slow. A 2006 ferry feasibility study concluded a commuter service was too expensive to pursue at the time, but that it could be viable in the future if certain things happened. The first such condition: “degradation of vehicular travel time on roadways parallel to the river that give a water-born transit a distinct travel time advantage.” If the vehicle in question is a bus, the travel time’s never been that great. The trip between the heart of St. Johns and downtown Portland takes an advertised 30 minutes on TriMet's infrequent 16, but it's a lot longer if there's a freight train crossing on NW Naito or a backup on the St. Johns Bridge ramp. The 44 takes, well, about 44 minutes, and the rather roundabout 4 takes at least an hour. (No one in their right mind would take the 4 that whole way, of course; the savvy downtown commuter accesses the Willamette side of the peninsula by taking the Yellow Line MAX to the 44.) The ferry ride between Cathedral Park and RiverPlace would be 25 minutes, though if your destination is not Cathedral Park or RiverPlace you'd have to add transit time on either end. A future stop closer to the OHSU tram is a possibility, but particularities of the Zidell riverfront property preclude a ferry dock there at the moment.

Proposed stops beyond the pilot project

2. The population is growing. Another game-changer, according to that killjoy 2006 study, would be a population increase of 10 percent in riverside communities at least 20 minutes from downtown. St. Johns’s 97203 zip code has seen a boost of 10 percent in the past decade, and Frog Ferry boosters say 300 to 500 OHSU employees live in the area that would be served by the St. Johns stop. Oregon City's population has increased by at least 25 percent since that old study came out. Heck, if this thing is a go, it will be hard to resist moving to Oregon City and getting a job on Marquam Hill just so you could ride a municipal elevator, a ferry, and a tram to work and back. Roads? Where we're going, we don't need roads.

3. Housing density is increasing. The 2006 study also cited “a significant change in development patterns (i.e., multi-acre, high-density residential or mixed-use development)” as a sign of future ferry friendliness. At the press event, Cathedral Park Neighborhood Association past president Jennifer Vitello pointed to the 2015 Cathedral Park Waterfront Plan, created by Portland State urban planning students, for a glimpse of what was coming. City permit applications and zoning change requests show plans for the area that include a 15-acre site with “multi-dwelling residential, retail, office and manufacturing uses” and a separate four-story, 110-unit apartment building. A transit option that wouldn’t always involve the walk up the steep hill to downtown St. Johns (a hill that’s too steep for traditional buses) would be most welcome.

4. This Frog has friends. Ferry supporters hope the Biden administration will be generous to alternative transit—Biden is "Amtrak Joe," after all. In a more local seat of power, there’s a friend ensconced at city hall in Adams. At the campaign launch, he spoke of having run for city council in 2004 with the dream of being transportation commissioner. (He defeated Nick Fish that year—frankly, the late Fish had a better river-transit name.) But much of his term as a city commissioner was spent dealing with cost overruns on the Portland Aerial Tram project, and in his one term as mayor, when he was largely hobbled by a sex scandal involving a minor, he didn’t give us a ferry; he gave us an arts tax.

Two versions of the Frog Ferry logo at the Cathedral Park press event on June 8

Image: Margaret Seiler

5. It has a logo. Yes, it has a logo. And the words next to the logo are no longer always displayed in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer typeface like they were in early presentation documents (and on the parking attendant's polo shirt, pictured above). At least it wasn’t some Helvetica copout or Papyrus crime against humanity, but Joss Whedon and his toxic-work-environment allegations might not attract as many partners as these new bold caps. At the Cathedral Park event, the logo was everywhere: on face masks of speakers, on the quarter-zip pullovers worn by people holding large foamboard displays, on signs differentiating media and dignitary parking from the farther-away supporters parking, on a baseball cap worn by someone in the front row who asked the speakers to talk more about how great the ferry would be. The cute green frog (from Northwest artist Adam McIsaac, whose work also hangs at Skamania Lodge, inspired by Chinookan mythology) does look like a friendly local and not, say, the invasive American bullfrog, but it could just as easily be an illustration for a wetland cleanup effort or an estuary interpretive center or a tropical pet store. From far away, it might be the Adidas trefoil or a pot leaf. But it's a frog. After all, a fish could imply the boat might sink underwater, a Portland-appropriate slug would send the wrong message about speed, and beaver, deer, and owl were claimed long ago by TriMet for its old sector symbol system (RIP). Still, Frog Ferry has a logo, and when something has a logo, you know it's serious.