If Portland Has to Grow and Grow, We Have a Few Demands. Better Sashimi, for One.

Image: Matthew Billington

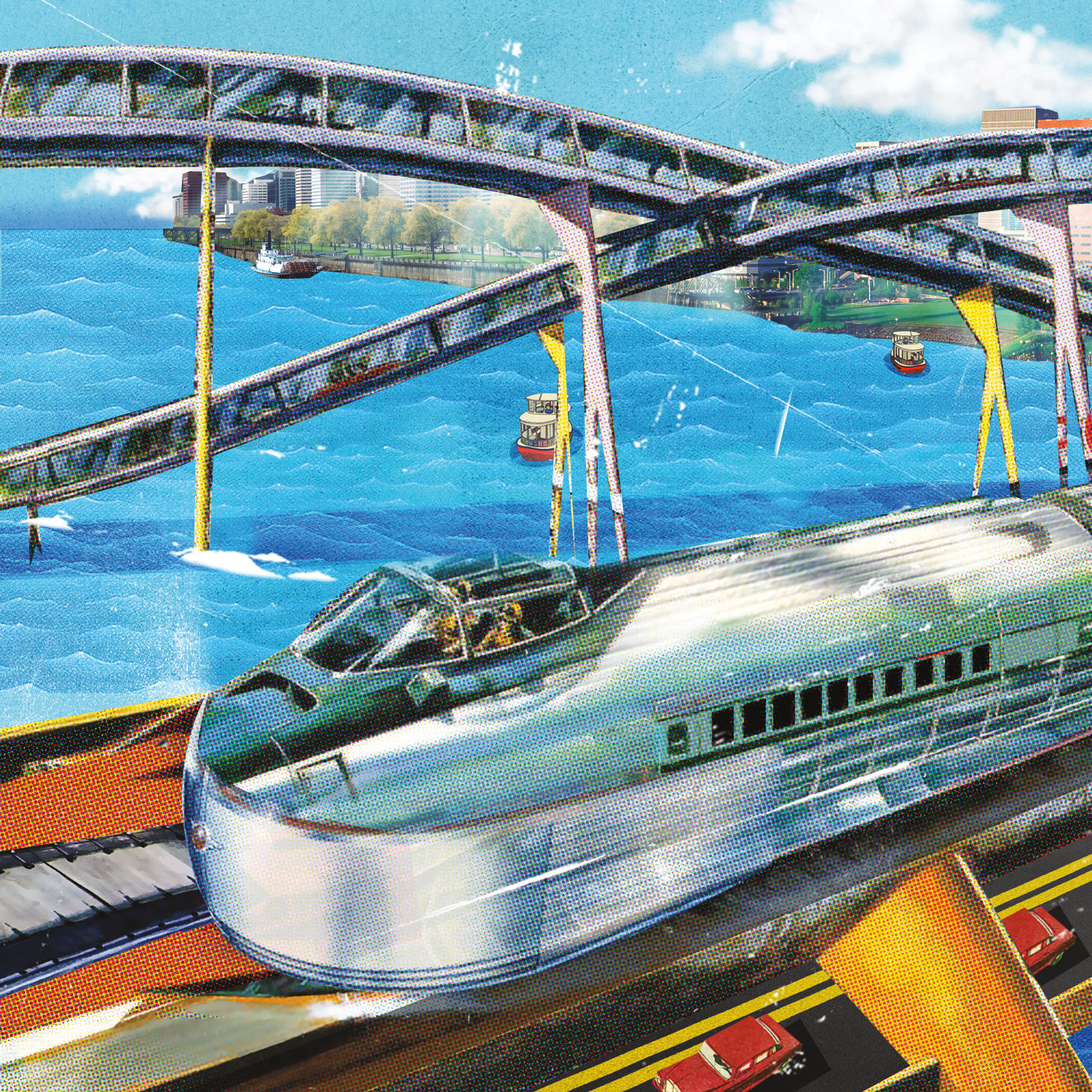

What We Want: Water Taxis

What It Would Take: A transformed waterfront. Road traffic even worse than it is now. Loads of cash.

“It’s easily the highlight of my day. A boat to work—that’s the way to go,” says John Ferguson, who lives in Algiers Point (a sort of St. Johns of New Orleans) and bikes a few blocks to the dock before a 10-minute Mississippi River crossing to his restaurant job. (The bus might take an hour.) In Seattle, commuters can zip across to West Seattle or Vashon Island on a King County Water Taxi. In Baltimore, a Harbor Connector is a godsend for commuters to Under Armour’s Tide Point HQ, across the water from the hip areas of Fell’s Point and Canton. Then there are ferries and water taxis in New York, Vancouver, Brisbane, Istanbul….

Why can’t we have these nice things? “Commuter ferry service should not be pursued at this time,” stated a 2006 Portland study, one of several over the decades that all reached the same conclusions: not cost-effective, limited by lack of access points, not competitive with bridges and existing transit. A tourist circulator is the only idea the studies ever endorsed, but even that would demand huge investment.

Still, why shouldn’t Portsmouth residents cruise the Willamette en route to Slabtown offices? Maybe a visionary will see the possibilities: Kevin Plank, Under Armour’s founder, recently bought Baltimore’s water-taxi system. Kevin, come sail with us! —MS

What We Want: A Subway System

What It Would Take: A miracle of untold proportions. (But it is a good idea.)

In 1906, Portland mayor Harry Lane wanted to replace the failing Madison Bridge with a subway line underneath the Willamette. “A subway would cost only about twice what a bridge will,” he said. “Bury the bridges as they fall and build subways instead.”

Instead, the city erected the Hawthorne Bridge and never looked back.

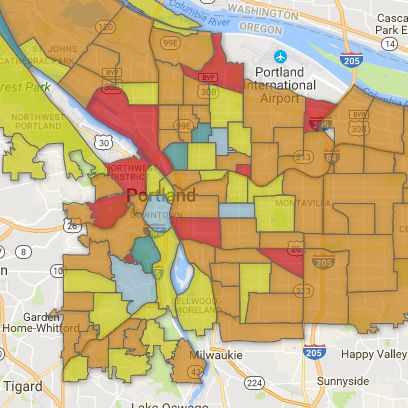

Now, Portland faces a traffic crisis. As freeways clog, TriMet buses and trains that often share space with cars don’t seem quite adequate to the escalating task. The city’s transportation bureau expects another quarter million new Portlanders by 2035, with about half commuting. Harry Lane, where are you?

There is a recent precedent: the six-mile East Side Big Pipe, completed in 2011 for $450 million, ferrying sewage (not passengers) 150 feet belowground. At 22 feet wide, the tunnel could accommodate a MAX train. And, in the heady days of 2009, dreamers at Metro actually considered a downtown subway, connecting Lloyd Center and Goose Hollow with a single stop at Pioneer Courthouse Square. The tunnel would have reduced MAX times between the two ends by 12 minutes. Metro balked at the $2.2 billion price tag, and predicted that a single, central stop would serve fewer people than the current system. (“More stations could be built,” the agency concluded, “but the travel time savings would be correspondingly less, diminishing returns for ... one of the most expensive projects ever built in the region.”)

But subways simply work. Take New York City’s aging G Line between Queens and Brooklyn. Average speeds along its 11-mile track are about 8 miles an hour slower than Portland MAX trains average. But this single line, liberated from aboveground congestion, averages 125,000 weekday rides. That’s about half of TriMet’s daily haul—all of TriMet, buses and trains. As we face 21st-century traffic-pocalypse, maybe it’s time to dig deep . —MP

What We Want: Truly Great Sushi

Image: Matthew Billington

What It Would Take: Diners willing to pay LA prices for Tokyo ambition

Nodoguro’s Ryan Roadhouse has worked at both ends of the sushi spectrum. He’s blitzed through 700 customers a night at Denver’s Sushi Den, and plated nigiri for the now-defunct 10-seat, $398-per-head Urasawa in Los Angeles. When he relocated to Portland to work for Bamboo Sushi in 2009, our scene was a shock to the system. “I got the sense that sushi wasn’t much different here than in Cleveland, Ohio—no offense to Cleveland.”

In other words, Portland is generally a conveyor-belt sushi town, where deep-fried cream cheese rolls prevail over urchin nigiri. With a few exceptions—including Roadhouse’s own “Hardcore” 11-course raw fish odysseys, or Murata’s tatami-shrouded traditionalism—no one ships premium-grade cuts from Japan’s Tsukiji fish market, like you might see at New York’s Sushi Yasuda or Masa.

It all comes down to price point. “Portland is an extremely value-conscious town,” Roadhouse says. “When I was at Bamboo, people gawked at the idea of $100 omakase for two people.”

Still, Portland’s sushi budget may soon catch up with its growth. Roadhouse charges $125 for a Hardcore meal, with soy-cured fatty trout and yuzu-washed king salmon. Seats for those special nights sell out faster than other meals at the small, reservations-only restaurant on Southeast Belmont, typically disappearing in a matter of hours.

We’ll keep dreaming of a Jiro-type maestro serving barely legal, exquisitely fresh sashimi. But if local tastes (and spending) keep maturing, dreams might come true. —BJ

What We Want: A ‘Night Mayor’

What It Would Take: A budding politician who likes to party!

Image: Matthew Billington

Amsterdam appointed the first “night mayor” in 2014. Paris joined in, giving the job to a lank-haired hipster named Clement. Last November—something good happened in politics!—London became the world’s largest city to experiment with the role, there ominously called the Night Czar. While details vary, cities across the world are designating official voices for nightclubs, bars, cafés, music venues, and party people generally.

With gentrification threatening London pubs and clubs, Amy Lamé took office charged to link nightlife businesses, local government, police, and transportation services. The pioneer, Amsterdam’s Mirik Milan, emphasizes urban nightlife’s economic heft and ushered in longer hours for nightclubs and innovative street safety programs.

Why does Portland need a “night mayor”? Our music venues face a miniature version of London’s gentrification problem. We have a metro transit system that essentially stops running before closing time. Police tension has dogged our growing hip-hop scene for years. It’s time our nocturnal side got a seat at city hall. We’re sure we have our own version of Clement who would eagerly take a volunteer advocacy role—provided no meetings are scheduled before 11 a.m. —ZD