Decision Time: What to Know about Oregon's 2022 Elections

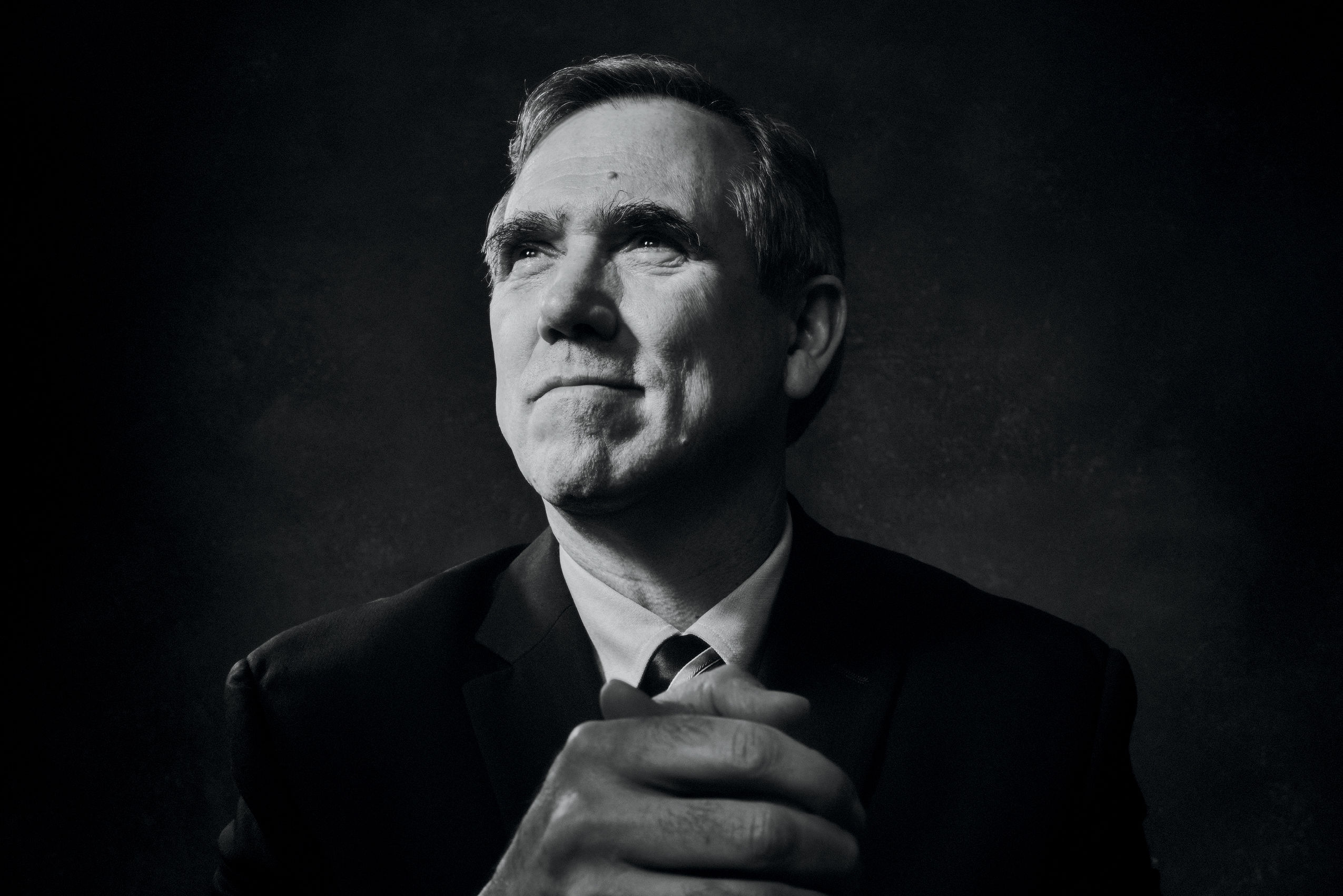

Image: Martin Gee

For the past decade plus, Oregon’s metaphorical Mount Rushmore has been unchanging: an all white, almost all male group of political leaders, many of them well into their 70s, occupy the state’s highest offices, from US Senator to governor to the five members of the state’s congressional delegation. (Gov. Kate Brown and Sen. Jeff Merkley, both Democrats, are the spring chickens of the group at 61 and 65, respectively.)

In 2022, that all starts to change. The year has the potential to be “the most transformative Oregon election in my adult lifetime,” says Ben Bowman, a former Democratic staffer in the Oregon Legislature and current candidate for the state House of Representatives who contributes to The Oregon Way, a state politics newsletter.

The list of subplots is long and juicy: The governor’s race is without an incumbent or former governor for the first time since 2002. The state has added a new congressional district for the first time in 42 years, and another seat will be incumbent-free for the first time in 35 years. And voters will weigh in on a massive and long-overdue change to how Portland city government is structured.

“We will have seismic activity from the campaign and electoral side,” says Rebecca Tweed, a political consultant who has worked for Republican candidates and on dozens of ballot measure campaigns. “There will be more competitive races that you would have never seen six years ago.... Maybe what Oregon really needs is changing how things have always been done.”

Let's start with the governor's race. On the Republican side, the field is crowded, with Salem oncologist Bud Pierce, who was his party's nominee for governor in 2016, making another run at the office. He'll face opponents including Sandy Mayor Stan Pulliam, who has been a steadfast opponent of COVID-19 safety mandates, and House Minority Leader Christine Drazan, of Canby. Of note: Should Drazan win the nomination, she'd be the first female GOP candidate since former Secretary of State Norma Paulus in 1986.

On the other side of the aisle, North Portland Democrat and longtime House Speaker Tina Kotek, 55, is busily locking down support from the state’s powerful public employee unions—just this week, the Oregon Nurses' Association announced its support for her candidacy. Donations and get-out-the-vote efforts from public employee unions have proven insurmountable in Oregon's recent history. Should she win, Kotek would be the first lesbian elected as a governor in US history. (Brown, the governor since early 2015, is bisexual.)

In the nearly 15 years she’s been in Oregon politics, Kotek’s hair has turned, Obama-style, from brown to gray—no surprise, given her role running the often-fractious Oregon House. As Speaker, she helped pass bills to raise the minimum wage, end single-family zoning, and establish a family-leave policy, though she’s faced criticism for a lack of urgency on Portland’s future and for not moving fast enough on police reform. Under Kotek, the state could elevate its outsize rep as an incubator for progressive policies, while continuing Brown’s labor-friendly fiscal policy.

One wild card that could complicate matters is former State Sen. Betsy Johnson of Scappoose—the longtime (but no longer) Democrat known to be a very business-friendly and an occasional foe of organized labor and environmentalists, a.k.a. Oregon's own version of thorn-in-Joe-Biden's-side Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia. Johnson is running as an independent candidate and could siphon votes from both parties. Her early fundraising totals have been eye-popping; she has nearly $2.4 million on hand, and happens to own and fly her own plane, handy for any statewide candidate. She's also got the distinct advantage of not having to face a bruising primary—instead, she can just sit back and raise money until the dust shakes out in May. Johnson doesn't even have to worry about the upcoming legislative "short session" in February; in mid-December, she resigned her position to focus full-time on her run for governor.

Of course, Kotek could get knocked out in the primary by a competitor—be it New York Times columnist Nick Kristof, who has returned to his boyhood home on a Yamhill County farm and is attempting to bridge the urban-rural divide, or State Treasurer Tobias Read, who has roots in the Portland suburbs and has been particularly outspoken about the toll that a year and change of remote learning took on kids through the state.

Win or lose, though, Kotek will no longer be Speaker of the Oregon House, marking a whole new era for that body, too. Whoever takes over has wide latitude over policy and budget decisions, plus the job of keeping a sometimes-fractious Democratic caucus intact and hanging onto the majority.

Rep. Janelle Bynum, D-Happy Valley, 46, is seen as Kotek's likeliest successor. Bynum, who is one of only a handful of Black lawmakers and has led police reform efforts in Salem, could usher in a new era of policy focused more squarely on racial equity, with a dash of business-friendly pragmatism. Meanwhile, at press time longtime Senate President Peter Courtney, D-Salem, 78, had yet to announce whether he’d run again, but here’s a clue: when the dust settled from a contentious redistricting process, Courtney’s seat had gotten far more competitive. Retirement could give him a graceful out if he wants one.

Turnover is also coming to Oregon’s congressional delegation. Democratic Rep. Peter DeFazio, 74 and one of the longest-serving members of Congress, announced his retirement earlier this month. His district had tinged purple in recent years, but the 2020 redistricting made it a safer bet that a Democrat not named DeFazio will be able to hang onto the seat. First to declare that she'd seek it was Labor Commissioner Val Hoyle of Eugene, who is connected to national political money via Emily’s List and gun control groups.

Up in Multnomah County, Rep. Earl Blumenauer is running again in 2022, but given that he is also a septuagenarian, his seat might well be open in 2024 or beyond. Watch for Multnomah County Commissioner Susheela Jayapal—significantly, the only member of the current county board not to launch a campaign to be its chair—to make a run at Blumenauer’s seat when he finally retires. (She'd join her sister, Pramila Jayapal of Washington state, who is considered a progressive force in Congress.)

US Rep. Kurt Schrader, 70 and a fiscally conservative Democrat, is seen as being vulnerable to challenges on both the right and the left. The redistricting process shifted the population center of his district east to Bend, separating him from the bulk of his previous constituents. He's running again, but faces a primary challenge from Jamie McLeod-Skinner, who is to his left and previously ran for secretary of state in 2020. On the Republican side, former mayor of Happy Valley Lori Chavez-DeRemer is getting some national attention for her candidacy.

As for the state’s newest congressional seat, running from Portland’s populous southwestern suburbs to Salem, it has drawn interest on the Democratic side from a decidedly younger, more female, and more ethnically diverse slate of candidates, including state Rep. Andrea Salinas, D-Lake Oswego, and former Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith. (The Republican slate is still shaking out, but McMinnville state Rep. Ron Noble will run for the seat.)

“These [redistricting] maps are going to reflect the ways that Oregon has grown and changed,” says Annie Ellison, who worked on campaigns for both current Secretary of State Shemia Fagan and, in his first run for city hall, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler. Ellison now runs Emerge Oregon, a training program for Democratic women who want to run for office. “We are getting younger and more diverse. Wherever in the state it looks like the most competitive opportunity is, we will have a great woman candidate ready to go.”

C andidates come and go, but in November 2022 it will be Portland city voters who could have the longest-lasting impact—not for a particular office, but for a possible change to our beleaguered and archaic commission-style form of government. Changing the fundamentals of how the city is run via a possible overhaul of the city’s charter (which is to the city as the US Constitution is to the country) is once-in-a-century stuff.

Under the current structure, city council members both make and direct policy, often without any expertise in the area of the bureaus they are leading, a system critics say breeds a lack of accountability and transparency between elected officials and those they represent. The mayor is charged with assigning bureaus, but apart from that has no powers beyond those of the other four members of the city council.

By contrast, other major American cities either have a “strong mayor” form of government, with broad executive powers assigned to the mayor, or a city manager who is responsible for the day-to-day of bureaus, leaving mayors and councilmembers to focus on policy-making.

Voters could also be asked to reform city elections, perhaps choosing councilmembers by zone or expanding the council’s size. Proponents say such changes would result in a more diverse, responsive group of city council members.

Andrew Speer, a member of the group charged with reviewing the city’s charter, says reforming city government is central to enacting the concrete changes sought by the thousands who took to the streets in Portland in the summer of 2020 to support racial equity and social justice.

Portlanders have had the chance to vote on charter changes before (most recently in 2010), and always stuck with the status quo. This time feels different, given the widespread sense that Portland is floundering, though Speer says he’s aware the city’s most powerful players may prove unenthusiastic about changing a system that has served them so well for so long.

“The city’s charter is its governing document,” says Speer. “Within that, there are systems that may not serve some constituents in an equitable way. And so, this (charter review) is essential, for peeling back the onion, and being able to understand where the inequities lie, and what changes are needed.”

Change of this magnitude in Portland could have ripple effects in the rest of the state, according to Tweed, the Republican consultant.

“Changing this in Portland could be the catalyst for change in other local governments,” Tweed says. “It is time to do something a little bit different.”