It's a Non-Affiliated Voter's World Now—and They Can't Vote in It

Primary Day is a little over a month away in Oregon—but for more than a million of the state's non-affiliated voters, that doesn't mean much.

For political junkies trying to read the tea leaves before the upcoming May 17 Oregon primary, there’s a potential clue or two in the latest round of updated voter registration numbers, released this week by the Oregon Secretary of State’s office.

Democrats—recently knocked off their perch as the state’s biggest group of registered voters—lost another 1,318 voters. Republicans, while still a far smaller group overall in the state, gained 1,327 new voters—almost exactly the same total.

The real headline, though, is that voters who’ve declined to register with any political party, known collectively as non-affiliated voters, or NAVs. Oregon's NAVs added another 4,583 voters to their ranks, in a year when they’ve already leapfrogged Democrats to become the state’s largest group of voters, period.

To be exact, there are now 1,027,139 voters who are registered as non-affiliated with any party in Oregon, against 1,018,350 Democrats and 725,055 Republicans. (139,628 people are registered as members of the Independent Party of Oregon; several other smaller parties have a few thousand members apiece.)

The rise of the non-affiliated voter is traced directly to Oregon’s much ballyhooed “motor voter” registration program, which kicked off in January of 2016. That law made voter registration automatic when obtaining or renewing a driver’s license, meaning that hundreds of thousands of younger voters, in particular, who might not have bothered to register before were suddenly added to the voter rolls.

The numbers tell the story: in December of 2015, right before the motor voter law kicked in, there were only 527,302 NAVs in Oregon—just under half of today’s totals. (Republican and Democratic ranks have grown too, but at nowhere near that dizzying pace.)

Adding so many people to the voting rolls is good for democracy—but there are serious downsides to the way the current system is set up, thanks to the state’s closed partisan primaries, says John Horvick, senior vice president at Portland polling firm DHM Research. (Under a closed primary system, only registered Democrats or Republicans can vote for their party’s candidates in partisan races. Nonpartisan primary races, like those for the Portland City Council, remain open to all.)

“We are, every day, every week, every month, shrinking the pool of voters who can vote in a primary,” Horvick says. “And I don’t think that was the intent (of motor voter), but it is certainly the outcome.”

The issue is of particular relevance this year, the most consequential primary in Oregon in at least two decades, given an open gubernatorial seat, a crowded field of candidates for both major parties, and a new congressional seat at stake. Also worth considering: despite the fact that more than a million of the state’s voters can’t participate, taxpayers foot the bill for partisan primaries, to the tune of about $4 million.

The new ranks of non-affiliated voters have some clear defining characteristics, Horvick says. They skew younger, and are more likely to be people of color, in keeping with that demographic, though Oregon does not track race when registering voters. That should be of particular concern to the Democratic party, Horvick says, given its traditional base, and yet he says he sees “no urgency or concern” from Democratic leaders.

“The process we have is decreasing participation. And it is decreasing the voice of the voters they claim they want to most encourage to participate. It’s inconsistent with their other positions,” Horvick says. “In some respects, I don’t find it baffling. Democrats win in Oregon, under the current system. So I’m sure there is a strong status quo bias, but I do think it runs directly counter to what their other stated positions are.”

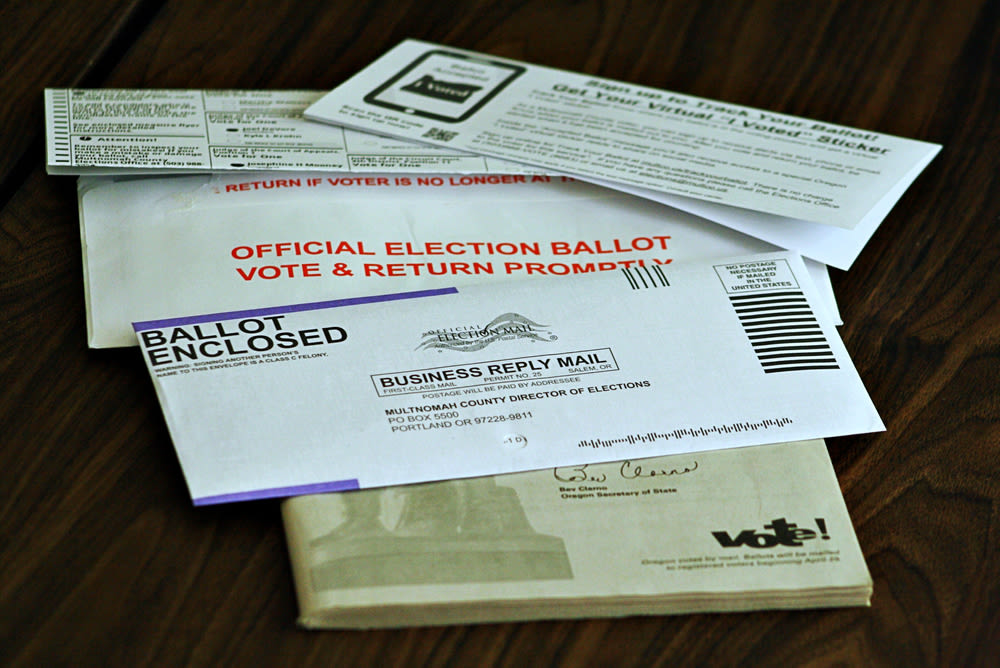

Though Oregon is often a leader in election reform—vote-by-mail, anyone?—the state is lagging behind neighboring Washington and California in primary reform. Both of those states have moved to “top two” ballots, in which all candidates appear on every ballot, and the top two vote getters move on to the general election, regardless of their party. Horvick also likes Colorado’s approach: that state mails every voter both a Democratic and Republican ballot, and lets them choose which one to return, regardless of their party.

Previous citizen-backed ballot attempts to mandate open primaries in Oregon have failed. A loosely organized effort to put a measure on the November 2022 ballot is underway, but organizers have just $6,513.47 on hand, far below what is typically needed for a successful statewide ballot campaign.