Review: VANTAGE

Kudos to Archer Gallery Director Blake Shell for curating a group show magnetic enough to draw most of Portland’s plugged-in arts worlders over the river and through the freeway interchanges to the gallery’s Vancouver, WA location. The works in VANTAGE dealt with the altering, questioning, or redefining of perspective or space. This meant bending reality both sonically, as with Greg Pond’s “That Intricate Never” and visually as with Isaac Layman’s photos and Avantika Bawa’s installation.

Layman makes hyperreal photos of everyday objects. Shooting objects from subtly different vantage points and depths of focus, Layman then digitally layers them together to create a single, vivid, oversized image of a kitchen untensil drawer or the back of an old stereo. If Daniel Peabody of Elizabeth Leach Gallery hadn’t pointed out the minute distortions of angle on “Stereo,” (Layman’s work is part of a group show at Leach next month, I believe Daniel said), I’m not sure if I could have identified what was odd about the photos other than their unusual crispness and feeling of being somehow more-than. In a way he’s Andreas Gursky writ small, borrowing method and mundane subject, but focused in on a micro-level, object rather than landscape. By compositing the photos, Layman is actually able to load a finished work with more visual information than one photo could ever contain. In this way, like Stephen Slappe’s work with video (see below) Layman toys with the viewer’s expectations of the medium.

I’ve seen Victoria Haven’s photos of angular geometric forms and their shadows at PDX Contemporary Art. The forms fascinate me because they capture the ongoing fascination with and ubiquity of crystal-like and triangle-based forms in design and because they’re created by running string ’round points or nails hammered into a wall recalling both Naum Gabo and 70s craftsy string sailboats nailed into redwood boards, but have a sketch-like looseness making it seem as if the nails fell where they may. I love their drawing-like nature and their subtle implication of dimensionality.

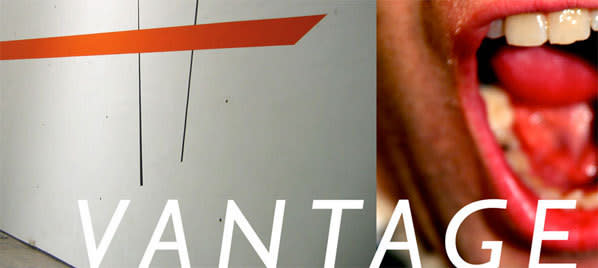

I walked in on Stephen Slappe’s video, “Bear Witness,” near the end of its running time, the camera panning across a man’s mouth open wide and the serene scene of a cemetery framed in a horizontal rectangle as if viewed through a doorway or a slot. The panning was a device I’d seen him use before: the camera slowly and repeatedly panning 360 degrees. Watched from the beginning, the figure, a male in a hoodie is first pictured standing still. As the world turns (ha!) he appears closer and closer to the camera slowly enacting the arm stretch and gaping mouth of a yawn. As he gets closer to the viewer, the figure seems to detach from the background and float free until the open mouth consumes the field of vision on each swing of the camera with what could be a yawn or a scream. Either is an entirely appropriate and inappropriate response to the pastoral and tragic setting of the cemetery, making the detachment multivariate—physically and emotionally. But what’s more interesting is the work’s comment on the "realness" of the medium. If we have not yet lost our illusion that the camera can be trusted to bear witness, Slappe asks us to reconsider.

Like a wallpiece in a Karim Rashid boutique or the disco great-great-granddaughter of a Hans Arp relief, Golan Levin’s animation appeared to be a futuristic, pulsing grey blobject hovering in a white field. Levin has digitally mapped points on Merce Cunningham’s fingers and knuckle joints during a performance to create this “field of simulated energy.” Cunningham, himself, extensively used a 3-D motion creation software program called Life Forms (now called Dance Forms) as a choreographic tool. If for Cunningham the software’s representation of the body was a midpoint on the way to movement, for Levin the representation is the end, body in abstraction carried to extreme in isolation. I’d be interested to see a choreographer take this animation as a score to create a piece for ten dancers.

Avantika Bawa’s corner installation “Points (for Brunelleschi)” deals most directly with vantage point or perspective, a fact she shouts out in her title with a nod to the man credited with the discovery of linear perspective. Her installation features a pink sawhorse and simple geometric wall drawings that comment on their surroundings including the oblique angle the corner of the floor creates. What interests me about Bawa’s work is that she’s found a way, using shape and color, to move forward Robert Irwin’s minimalist project of making installation in response to the interior space when one might have thought Irwin had exhausted that line of inquiry. It’s not unrelated to work by Portland artist Damien Gilley whose wall drawings, if busier and more illustrative, seem to come from a similar place. Bawa has begun a residency at Milepost 5. I look forward to seeing what she does there.

As always with a sound piece that is responsive to its environment, who could know what Greg Pond’s “That Intricate Never” was really up to when the room was as crowded and loud as it was at the opening. Its form reminded me of a good old fashioned coastal foghorn, an octagonal box with a speaker on each face connected to two mic’s on the ground and a box (in which the guts of the machine must have been) resting on a white fuzzy rabbit fur (nice touch, as were the braided cords cascading from the speaker box). We’re told via the show notes that the sculpture modifies the room’s sounds depending on their wavelength and volume using open source software. I appreciate that Shell included this sound piece to expand the notion of our vantage point to include other than the sense of sight. I wonder whether it might not have been better placed in the center of the room. And of course, I’ll have to return to truly hear it.