Review: Sherman Alexie's Blasphemy

Sherman Alexie is one of the country’s most celebrated writers (three-time PEN award winner, 86-weeks-and-counting on the New York Times bestseller list, crowned by indie Hollywood), a star in his native Pacific Northwest, and probably needs little introduction. That he is both a Spokane Indian tribesman and a successful writer who grew up on a reservation in eastern Washington are facts he will never let you forget. Throughout his published work (now inching into the double-digits) and in his disarmingly hysterical book readings and live appearances, Alexie returns to "the rez" again and again for its linguistic tics, the enormous blank canvas of its domestic isolationism, and, like many other writers before him, a setting to explore the peaks and valleys of our continual coming of age.

Alexie visited Portland in late October in support of his latest book, Blasphemy, sitting in on OPB's Think Out Loud radio program at lunchtime (and possibly causing listeners to spit Kombucha through their nose) and later appearing before his adoring audience at Powell's big-ticket literary outpost, the Badgad Theater, to indulge us all in a little "colonial S&M," some routine reading, and more than a few hilarious anecdotes from his life normally reserved for private sessions with his therapist. Extended, barbed razzing of Portland culture—from generic hipster hate to the over-saturation of Thai food cart options to "Portland reminds me of Seattle 15 years ago: sooooo full of itself!"—was met with some quizzical head-scratching. Not sure whether to laugh, clap, or get angry, the audience seemed genuinely alarmed that someone actually attempted to puncture the bubble and interrogate our infallible city (wink wink).

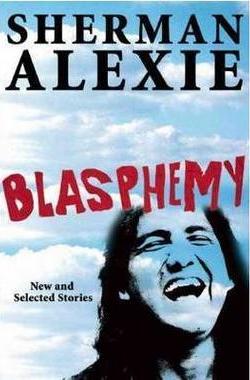

Blasphemy, a hefty hardcover story collection out now that spans the full length of his twenty-plus year career, is a convenient compendium for new readers and old fans alike. Not merely a "greatest hits," it also features recent and previously unpublished work to savor, and for the most part, despite his newfound success as a YA author, it is a polite reminder that we should be taking this writer seriously. Like the best storytellers, Alexie can toss off heartbreakingly expressive and profound sentiments with a humor and nonchalance that cleverly conceal their gravity. It's these deceptively poignant moments that drive Alexie's work and provide an earthly backdrop to the cosmic swap meets of our souls. His style mirrors the gruff poetics embodied in the archetypal caricature of the Indian Chief—speaking of worldly matters in descriptive fragments and showing rather than telling—a device Alexie mines for everything it's worth, translating the beauty of his forbears' straightforward philosophy into a jarring and transcendent literary experience.

A scene in "The Toughest Indian in the World" is particularly indicative of the thematic impulses underlying Alexie's most affecting work. The story finds a hitchhiker and the narrator in a motel after a long drive finding tragicomic irony in an unexceptional watercolor hanging over the bed that depicts the US Cavalry defeating a pack of Indian warriors. An exchange between the two men effortlessly illuminates the condition of displacement in the Native American experience: "'What tribe do you think they are,' I asked the fighter. 'All of them,' he said." And later, after an abrupt and unexpected homosexual encounter between the two strangers, their brief union becomes as meaningless and insignificant as the painting above their heads, and we see again the alignment of the various manifestations of separate but equal pain, realizing that one cannot exist without the other.

"War Dances," the centerpiece of this volume, is in many ways a triumphant convergence of Alexie's approaches to uncovering the tragically quarantined Native experience throughout history. Touching on grief, identity, and compassion through experimental narrative techniques and told with his hallmark wit and candor, it captures the splendors of this writer's considerable talent when let loose to wander the confines of his own thoughts.

During the Q&A following his reading at the Bagdad, an indigenous Mexican woman solicited Alexie's thoughts on immigration in light of the recent crackdowns in Arizona. Before addressing the question, Alexie focused on his visceral response to the inquisitor's honeyed voice, saying, "she could talk about genocide," and he'd still only be captivated by her voice alone. It was a real-time display of his ability to candy-coat difficult matters in a layer of humor so that we, as free agents on this earth bound together uncomfortably, can begin to understand the omnipresent Other—whoever it may be.