Night Air: A Short Story by David Shafer

I saw Orlando this morning. He was in a Starbucks on Fremont. I was riding by and I saw him through the window. At first I thought he was looking at me but it was still dark outside and he was only looking at his reflection in the window.

A Starbucks. Like my scriptwriters were trying to say something about banality, about how little there is to be retrieved from the thing I had with him that summer I got here.

I probably could have gone anywhere. Toledo. Ann Arbor. I just had to leave Scranton. And I liked the Oregon license plate. Seriously. That tree. It reminded me of an air freshener, like Oregon was being clever. So I followed the license plates out here, on those silky Interstates that may as well be called life choice flingers.

But I doubt there was an Orlando to be found in Toledo or Ann Arbor.

He was like his name sounded. He gusted up to you, like a trash cyclone, but his updraft wasn’t styrene bits and fecal dust, it was pure nerve, all comeonlet’sgo, like a dragonfly from a Greek myth had been made to take the form of a handsome 25-year-old in snug clothing.

This was 1995. I was 22. I got here in April and sold my car and bought a 10-speed Bianchi with mustache handlebars. I rented a room from my sister’s college roommate. I figured I had six months of money to live cheap. My only plan was to take classes towards my paramedic certification, because I wasn’t going to find a good job in a new city as a Basic EMT. But class was all of 12 hours a week and it wasn’t a difficult program.

The charm of not knowing anyone wore off in a few weeks, and you couldn’t really live cheap in Portland, even in 1995. So I got a job working in the kitchen at Stonesthrow. They had just opened and I was hired when I walked in the door. I worked in the back, peeling all manner of things, stretching plastic wrap over plastic bins.

Stonesthrow was the place that summer. It was where everyone ended up at the end of the night. Or I’m doing that center-of–the-world, Vaseline-on-the lens thing again, but I swear that joint was jumping. There was a pay phone by the firewood room and more than once I saw people crying on that phone, hanging on its metal cord. After-hours, Stonesthrow drew in the food-service night shift who had just come off work and weren’t about to go home, night owls with wine keys.

Orlando came into Stonesthrow late one night. We were like a fire lit by a magnifying glass. We first kissed beneath the spinning bread, and I swear that revolving loaf still does something to me. Soon my real days began at midnight, after work. We were in bed by four or five, ate toast at 10, parted ways at noon, I to my classes and a life-size model of the thoracic cavity, he to the grueling life of a bike messenger. They sunned like gulls outside the Ten-Four Coffee on Third, walkies clipped to the ratty straps of their bags. At sundown they moved as a flock to Captain Ankeny’s.

And Orlando was from Portland. That was exotic then, in my cohort. Everybody else came from somewhere, but Orlando was indigenous fauna. He was from North Portland, which even gave him a little bit of street —hard to come by in Wonder Bread City. He knew parts of this town I might still know nothing about, and we went everywhere on our bikes. He was so fast some nights it was like trying to follow Peter Pan. I was new to Cascadia, new to my 20s; I was unprepared for the scent of blooming flowers that filled the night air we raced through, didn’t yet have a handle on my mood thing.

The turn came in September. One night a flash of jealous rage. A two-day comms dropout very vaguely explained. Sometimes his eyes sparkled like it was June again, but more often he was grouchy and full of sighs. He declined blowjobs, turned his back to me in corners. Then he asked to borrow money. Then he got all glassy and inch deep. Then he fell asleep when we were eating Thai food on Burnside.

Ever realize, quite suddenly, that someone you love is deeply fucked-up? I knew Orlando smoked some weed and liked being drunk. But for some reason—probably his beautiful body, which I swear I saw every inch of—it would never have occurred to me that he was using speed and heroin in a savage and secret regimen.

Probably he started the speed in the autumn and then ramped up the heroin to try to get off the speed. (You have no idea what kind of sickening ride these people are stuck on. Or maybe you do, sorry. I’m a Labor & Delivery nurse at Emanuel now, but I was a field paramedic for 10 years. I’ve seen people leave that stuff behind them. A few. It’s just really bad odds.)

It turns out I knew nothing about Orlando. He was an artichoke of lies. It took a few months for the thing to play out, I think only because I was so surprised. Or maybe I wanted the punishment. It was in October that I finally saw the futility of it all, and somewhere around Halloween that I ended it. But by then I was pregnant and totally unaware of that, which we’ll put down to my contraceptive negligence, wingnut menstrual cycle and an apparently high aptitude for denial.

So there was a month I knew about it before I could terminate it, a month like walking through a fog. There was also real fog that autumn too I think. Or mist I guess— whatever shrouds the Fremont Bridge and makes Forest Park look like Narnia. Also I cried every day.

I did try to tell Orlando. I called the number I had for him and I asked around Ten-Four and the other places he might be. But he was MIA. On the day of the abortion I left a message on his answering machine. I didn’t want his input but I thought he should know. He had a cassette-tape answering machine, so maybe the tape with that message on it is sitting in a box at a junky vintage store, waiting for some lucky sound artist to find it.

I’ve drawn a curtain across my 20s. I’m told this is unhealthy but whatever. Yay, repression sometimes, you know? And I was alone through all that, I mean I was unencumbered; I don’t have a battle-scarred kid or a long-seething partner I’m in the hole with. I got out of it alone so it’s mine to forget about if I want to.

I only ever think about the Orlando baby I maybe could have had because of the next three pregnancies that I lost, the ones with Alec: miscarriage, miscarriage, stillbirth. I swear my four almost-children follow me around sometimes, like when I walked into Solids, that new kindercafé on Williams, and they bumped through the door with me like little balloons. I know: avoid Solids in future. I know: maybe Labor & Delivery nurse wasn’t the best idea.

Years later, at a birthday party, I met Orlando sister’s childhood best friend. She told me Orlando didn’t grow up in North Portland—he grew up in Dunthorpe. There were fake Roman columns in their floodlit garden. She said the parents were fabulous narcissists who left their children for weeks to go to Boca and Taos and places like that. The friend had once seen the mother hold a broken Champagne flute to her own neck; Child Services would have been involved but the parents were big shots, not to be fucked with. I asked her what had become of Orlando. She thought he was in Arizona. So yes still alive. That was about all she knew. She and the sister had grown apart. She said she thought Orlando might have had a “pretty bad drug problem.’”

I nearly coughed up my cake, but I think I just said “Yeah, he did.” I’d only just met the woman.

Do you know what Portland looks like from the roof of the Centennial Mills building, that timber castle on Front Avenue, crowned with a water tower? Probably not. And now you never will. They’re knocking it down, they have been for months. Taking it apart really—you can see it was pretty much made of sticks. Earthquake bait, I guess.

But I do. I’ve been up there.

It was Anton who called me that night. At first I couldn’t understand him, but when I did I told him go back up to the roof and get Orlando down. I grabbed my kit and got on my bike. By the time I crossed the river I guess I’d figured out what I was going into, so I ran into that bar with the porthole windows and called 911, told the dispatcher to get an ambulance to Centennial Mills.

I got into the building easily enough, But getting to the roof was dicey. It was eight stories and the stairs sagged; there was a warm, pongy updraft in the pitch dark. My Mag-Lite cut half a flight above me and made birds beat from the walls. I was in good shape, but the med kit was 20 pounds, and I was probably bleeding through a heavy pad. This was three days after the abortion. My heart was pounding when I reached the roof. I called out and Anton called back from beneath the water tower.

When I got to him, Orlando’s lips were fish blue and he was taking four breaths a minute. I employed a maneuver we call in the trade “shake the guy.” He flopped like the proverbial rag doll.

Now they’ll let any joker administer Narcan. Good, that stuff is magic. It’s an opioid antagonist that works in seconds. But back then you could only inject it, so only paramedics could carry it. I wasn’t supposed to have any.

I only gave Orlando a small amount, what we call a whiff. I must have done it right, because his eyes fluttered open and he took in the scene around him and he smacked his lips like he wouldn’t mind a sip of ginger ale and he said, “Glad you could make it.”

I suppose that counts as witty. I think he really thought I’d appreciate it. But when I didn’t, he pivoted; told me how torn up he’d been about the abortion. He said he’d been to treatment but it didn’t work for him, because he was too sick. He hated himself. He wept about that, about his hating himself. It did not occur to him to ask me if I was okay.

Narcissism is overdiagnosed. I have seen the real thing up close.

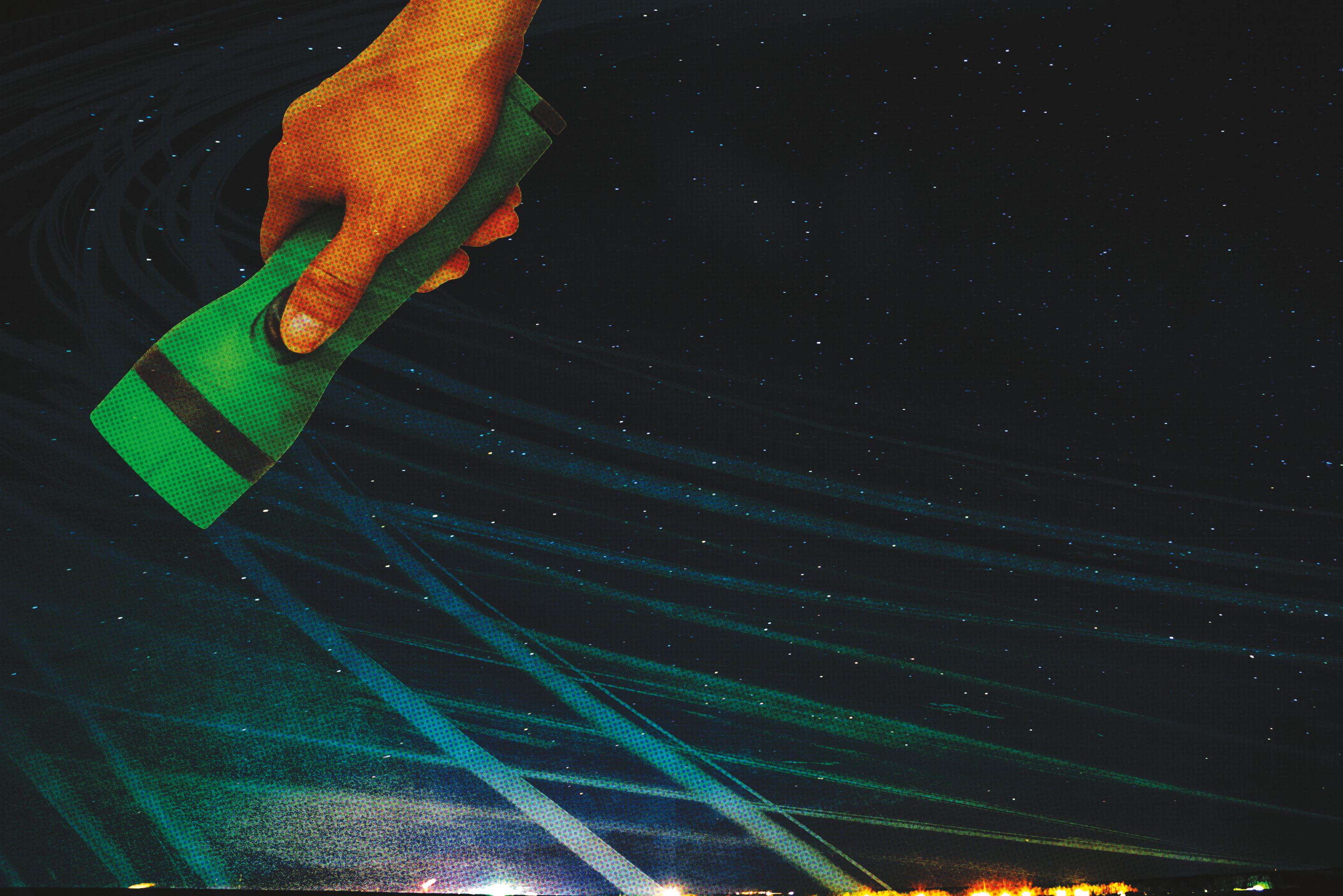

Then I heard the wail of an ambulance so I told Anton to stay with Orlando and I went to the edge of the roof to hail it with my flashlight.

It’s wild on that roof. It’s a mini-city of tarry sheds and skylights, knots of pipe and stacks. It was a clear night, Portland sparkled all around me; those radio towers on the West Hills beat their syncopated red and I could see the sharp dark line of Forest Park like the hem of the city’s blanket. If Portland has gods, Centennial Mills was their Pantheon.

I turned my flashlight to the sky and cast its beam around to be swallowed by the dark. Then this happened—maybe the only mystical experience of my life—in a moment, I felt a great lightness, and I knew that the life-thing that I terminated forgave me. Now listen: I have never regretted the choice I made, and I give the finger to those assholes outside Planned Parenthood whenever I bike by. But I did still want the thing’s forgiveness somehow. And on that roof, in that night, it was given to me. It came from the domed sky, the soft chill breeze, the winking lights, the hum off the bridge. It even came from Orlando, that cracked vessel I had patched.

All of it was plain and startling proof that there is a river of life flowing around us always, and that we only slip out of it for a while and we will all slip back into it one day.

David Shafer is the author of Whiskey Tango Foxtrot (Mulholland Books).