The Buried Forest: A Short Story by Margaret Malone

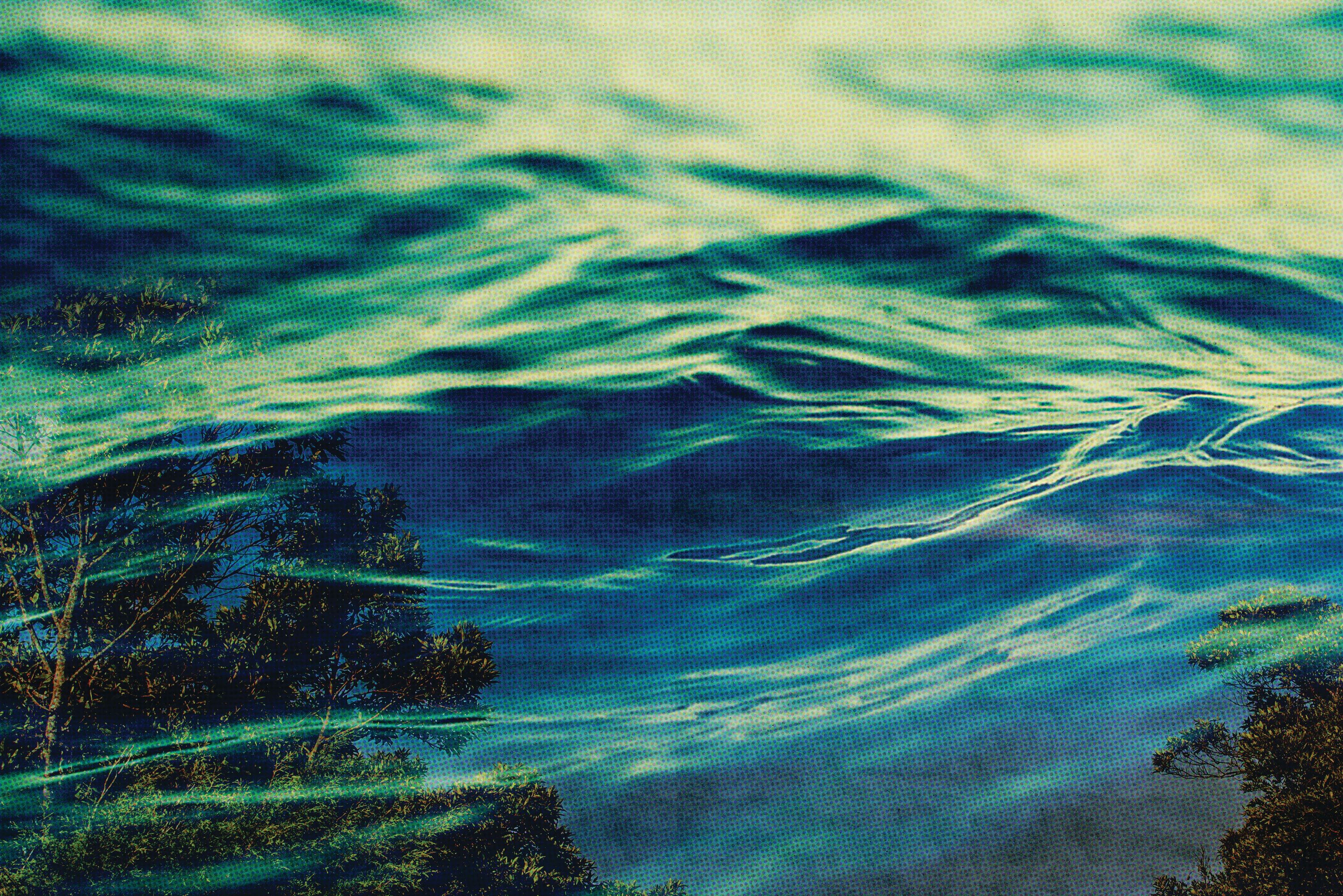

When I get there, nobody is on the beach but me and some other someone way down the sand. It’s drizzly and cold and I head for a good spot to wait for the trees to appear.

In high school, when we’d bring girls here, we made a big show of jumping the private road’s gate, walking past the fancy houses to the beach access. We’d supply the beer and weed and whip-its and light a campfire and none of us would ever remember a blanket and we’d tell whatever girls we could get to come with us that night, we’d tell them the story of how the trees came to be here, how they just showed up one day after the storm, came right up out of the water, though really they’d been there all along, for hundreds of years. Just nobody could see them yet. It almost always worked. At least one of us usually got laid.

Now it’s what I do when I don’t know what to do, wait here for low tide, for the old trees to grow up out of the sand and water.

The only other person on the beach gets closer. Hey, I know her. It’s that weird chick from the bakery who used to do that creepy thing with her eyebrows.

Crap, she saw me.

I raise my hand up in a sort of wave and wait to see if she’ll walk toward me or away.

“Hey,” I say.

“Hey,” she says back.

The ocean is loud, everywhere.

“You’re back,” I say.

She doesn’t say anything for a minute. Then she says, “My dad sent me out here again to live with my mom for a bit to figure my life out, but then she left to drink margaritas.”

“Huh,” I say. “At a Mexican restaurant?”

“No, like in Mexico,” she says. “She was really excited to go.”

A seagull screeches nearby. Then a pocket of quiet before the next wave.

“You like going back and forth like that, between them?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” she says. “It’s just what we do. That’s how we’re a family.”

We listen to the roar.

“You in school?” she says.

“No,” I say. “I’m old.”

“How old?” she asks.

“Twenty-six,” I say.

“Geez,” she says. “Old man river.”

“Hey, what happened to the bakery?” she asks. “I went by and it was gone.”

“Oh, man,” I say. I wish she wouldn’t ask that.

The bakery had been good for me, up every day at four thirty, off work by two. The same folks stopped by each morning in the same order. We were the only full-service bakery in town, handmade breads made fresh every day, cakes on order for kids’ birthdays. There was a rhythm to everything. Long as I stayed focused, things were simple.

The bakery owners, Jim and Liz, liked having me run the front counter. They thought the customers liked it too, having a young man serving them with respect.

But then, last winter, Jim had a heart attack right there by the main oven in back and died the next day, and Liz didn’t want to keep on without him. She sold the space to a couple who run a kayak business and Liz moved to Arizona to be near her daughter.

“Sucks,” I say.

“That does suck,” she says.

We wait together for the trees to appear.

“Hey, can I ask you something?” I say.

She doesn’t answer which I take for a maybe so I keep going.

“What was up with that thing you used to do with your eyebrows?”

“Oh,” she says. She turns her head away from me, her dark hair cut jagged at her jaw.

“I’d watch you sometimes,” I say.

She turns her head back. “Well, that’s not at all weird,” she says.

“There weren’t a lot of places to look,” I say.

“Sometimes when I’m stressed out, I like to stroke them with my first two fingers, like this,” she says. “It relaxes me.”

“Huh,” I say.

Then she says, “That’s the real reason my dad sent me back here. It freaked him out.” She told me it was a classic patriarchal double standard because for centuries men have sat around petting their facial hair and she didn’t understand how her stroking her eyebrows was much different. “I don’t see why it should matter if a man or a woman is doing the stroking,” she says.

It seems like I should say something but I’m not sure what. All I know is it’s getting colder and the cold drives my hands into my sweatshirt pockets.

“You going to stay in town for a while this time?” I say.

“I guess,” she says. She grabs her thick wool sweater and pulls it closer around her. “Mom loves it here. Quiet. Peaceful. Yeah, well, death knell, I say,” she says.

When she asks what I’m doing now I don’t want to tell her. Besides, I’m pretty sure I’ll stop after this season. My friend Carl, he paints the inside of people’s houses and he says he could use my help if I wanted some work indoors. Painting seems like a better bet for me. But I don’t know.

Instead I say that when the bakery closed, things got hard again. When she asks what that means I say I was back to smoking weed most mornings, sitting on a bar stool most nights. I mean, what’s the point of pulling yourself together, keeping yourself together, if one day you wake up, and the whole thing can just fall apart.

Then I started up with harvesting the moss, and that got me outside. A lot of times I’d need to wade deep into wet forest, up these steep hills, through the mud and salmonberry bushes, crawling sometimes to get to the best stuff. The more time I spent working outside like that, the better I felt, and the better I felt, the more I didn’t want that better feeling to go away.

Plus I dig being up close with a plant like that. Sometimes when I’m supposed to be cutting and bagging I’ll stare at the moss—its long tentacles weaving over and across, or growing straight up like tiny fir trees—and it all starts to look like a miniature forest. Like I am a giant standing over it all. A giant in some kind of fable.

It seems like we should sit but it’s too damn cold to do anything but stand.

“Have you seen them before?” I say.

“No,” she says. “Heard about it. The ghost forest, people said, but I’d never been. The bakery was the only place I liked in town.”

I told her how a long time ago, like a really, really long time ago, like, I don’t know, maybe thousands and thousands of years ago, this part of the beach wasn’t a beach; it was a forest. A forest full of great big looming old trees. And then something happened, I forget what, a tsunami or earthquake or something, and that’s when the forest slid into the ocean, or the ocean got bigger and turned the forest into a beach. I forget which. Most of the time, the buried forest is underwater, and the beach looks like any other beach around here. Cold and gray with rocks. Unless you knew, you’d never know what was going on underneath. But at low tide, they poke their heads out, and the underground forest appears, tree by tree.

Ahead of us, the sea moves and moves. It never stops. We watch it: closer, farther away. Closer, farther away.

“I came here when my brother died,” I say. “Which, he maybe didn’t really die, he just never came home from a fishing trip that morning.”

“Oh,” she says. Then she starts up that thing with her eyebrows.

“He could be anywhere by now,” I say. Maybe he just wanted to keep fishing a while longer. Maybe he never wanted to stop, so he stayed out there on the water, his pole stretched out on deck, hat pulled down over his face, the sun probably coming up. “I can’t blame him for not wanting to come back.”

The first person who encouraged me to harvest was Gil Beeman. It was right after the bakery closed and I had a lot of free time so I’d hang out in the parking lot by the boat launch, down on the river, with the other guys.

Gil, as always, wore his dirty baseball cap, trying to hide that bald spot he inherited from his bad-news dad. He was leaning on the side of his brand-new truck, the driver door already dented. He said a bunch of guys had partnered up, Stan and Arnie and Pete, and all you do is go into the woods and get the moss and then bring it down to Lars’s gas station.

“Lars is doing it too?” I said.

“No, he’s just, you know, like, the middle man.” Gil pulled his cap down. “He’ll weigh it, and then pay you.”

When I asked what they use it for, Gil said what did he look like an encyclopedia? Then we both watched an old guy we didn’t recognize launch his kayak in the water. He had fancy equipment and a deep tan on his bare arms even though the water here is always cold, but he seemed to know what he was doing. The current picked him right up and carried him closer toward the inlet. The plop, plop of his paddling quieter until the sound was swallowed back into everything.

I told Gil no. “I don’t think so,” I said. “Not me.” I told him I wasn’t into killing stuff.

“It’s moss,” he said. “It isn’t killing.”

“I don’t know,” I said.

Then he told me I was a pussy, and I said he was, and he said I was, and then I said, “Fine, I’ll do it.”

Wait until you see them,” I tell her. “They’re awesome. Kind of magical actually.”

“Magical?” she says.

“I don’t want to tell you how many times I got laid bringing a girl here.”

“Yeah?” she says. It’s the first time I see her smile.

“Oh yeah.”

“Like how many?” she says.

“Well, at least one,” I say.

“Wow, one,” she says. “No wonder you didn’t want to tell me.”

There is a heavy gray cloudbank smashed up against the gray water; gray as far as we both can see.

“Is that one?” she says.

A wet brown stump peeks out of the sand near us on the beach. Then we notice

another one farther down the sand. Then another. Still half an hour to low tide.

“I think a bug flew up my nose,” she says.

“Want me to get it for you?” I ask.

“Funny,” she says.

She wants to know what happens to the moss. “Where does it go?” she says.

“I don’t strip it all,” I tell her. “Not like some of the guys.” Just a long swath off a single tree or two. The feel of it thick in my hands. I love how alive it is. I don’t tell her that I went back once to a trunk I stripped, just to grab a little bit more, but the moss hadn’t grown back yet. The thing was just as bare as the day I pulled it off. I mean it never occurred to me that it wouldn’t grow back. I guess I thought it was like a vine or a weed. I didn’t know.

“Depends how good the moss is,” I say. “Flower shops like it. The quality stuff is big with car shows. Those cats glue it onto paper or fabric or something and use it like a rug,” I say.

“You ever been to a car show?” I ask her. She’s bundled up and squinting at the anciently old trunk stumps and doesn’t answer, so I keep talking.

“I’ve been once, up in Seattle, years ago with my brother. Women in little dresses and high heels leaning on brand-new cars. Their hands rubbing the shiny bodies. I thought all that green was fake plastic grass, like at the mini-golf.”

I don’t tell her that sometimes I miss the old guy Jim from the bakery so much it’s embarrassing. It’s not like he was my dad or anything. He was my boss. Still, it sucks. Sometimes the people that die, well, it’s easier to understand why they’re dead, and then other times the people that die, they are the exact wrong people to be gone.

“Ok, so it wasn’t just the eyebrow thing,” she says. “There may have been some pills washed down with NyQuil before a nap. Thing is, I was just tired. It wasn’t on purpose. I mean, has anyone ever thought that maybe Sylvia Plath was just tired and cold and trying to warm the house up? I have friends back home who think everything in the world is one big conspiracy, some powerful someone pulling all the strings, but, I don’t know, what if it’s all one big accident? One big oops? Then what?”

A few by us. Two there. More out in the low water. Craggy, bent, worn stumps. They stand still as the tide slips around them.

“I thought they’d be beautiful,” she says.

“I know,” I say. “It’s not that.”

“No,” she says.

The drizzle turned to rain now.

“I thought about counting them once,” I tell her. But a few trees into the count I stopped. I figured, forty? A hundred? What’s it matter?

I grab her hand. She lets me. We head into the trees that have bloomed up all around us.

Margaret Malone is the author of People Like You (Atelier26 Books).