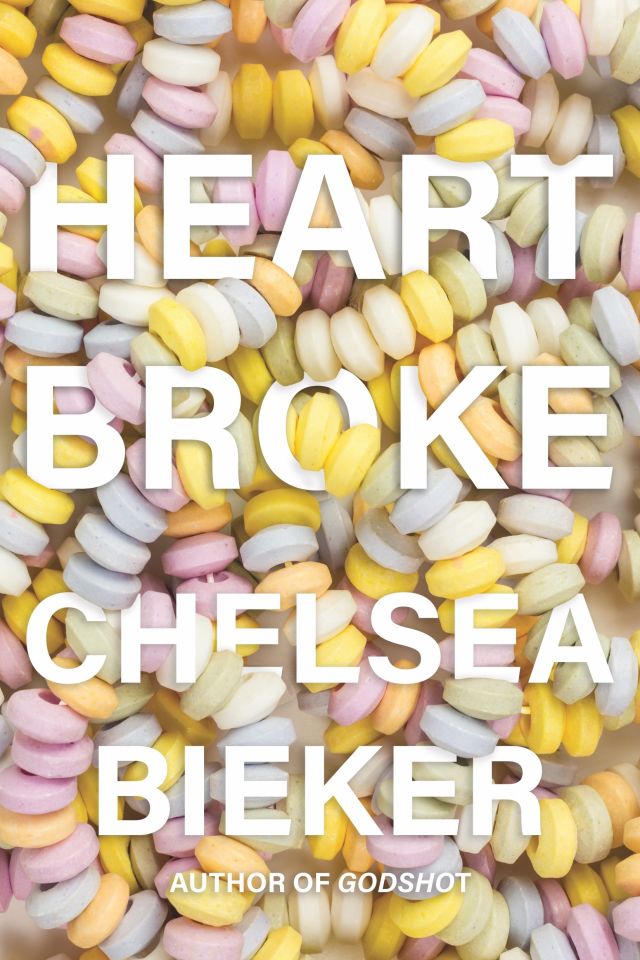

Portland Author Chelsea Bieker Returns with a New Short Story Collection

Image: Courtesy Jessica Keaveny

Header photo courtesy Jessica Keaveny

A brothel madam contends with unhealed wounds when a graduate student comes asking about an unsolved crime. A bartender is caught between a new love of writing and a controlling boyfriend named Spider Dick. A mother writes, but does not send, letters to her young gay son.

The characters who populate Portland author Chelsea Bieker’s first collection of short stories, Heartbroke (Catapult, April 5), stumble between addictions, resentments, and uncontrollable desires. In achingly beautiful prose, Bieker continues the work of her first novel, Godshot—nominated for a 2021 Oregon Book Award—spiraling the core of that Central California–set tale of abandonment outward into 11 new stories.

This is your first collection of short stories. How was the writing process for Heartbroke different than your process writing your novel, Godshot?

I actually started writing these stories before I ever started writing the novel. Some of these stories I started writing when I was 25. Now I'm almost 35. The stories that I wanted to tell were very voice-driven, and they feel naturally sustained by a shorter container than a novel. I revised them for a really long time. I really liked the challenge of the shorter container to tell a really big story.

Your stories are deeply rooted in the California Central Valley, where you grew up. How do you evoke a sense of place in your writing?

The California Central Valley is the place that has felt the most urgent for me to write about. I can see now, in hindsight, the ways these stories were me answering some questions I had about the stories I’d been told in childhood or the strange things I lived through.

For example, the story “Keep Her Down.” That was taken from a question I always had after hearing that my mom wanted to move in with my dad’s ex-wife. And I thought, What a bizarre thing that she wanted to do. And of course, the ex-wife said no, but I wondered, Well, what if she had said yes? That story was born out of that curiosity.

Your stories often involve non-traditional families: children acting as parents, or parents acting like children, or found families between traumatized people. Why is it important to tell these stories?

I think that it is a recurring theme in my fiction, where the child is taking on a parental role and the disastrous consequences that come from that. In some ways they do hold power over the parent, but then at the end of the day, they really don't. There’s a heartbreak in that because we know that the parents of these books probably won't make great decisions. In a lot of these stories, it's not about villainizing these “bad parents,” but trying to find the humanity in their earnestness and their desire for family, their desire for something good.

I think it was a subconscious thing that I was working out for myself. How do I forgive certain adults in my life who weren't really the adult? How do I move on from that? And how can I find humanity there? It's not easy, but it seems where my fiction tries to go. Maybe I'm trying to teach myself some lessons.

You’re very unflinching about looking at characters that are doing amoral things, but there’s still a lot of empathy there. What’s the value of that?

I think it's just a fantasy to imagine that these scenarios don't exist in real life. I don't come to fiction necessarily to encounter real life—I come to be put into worlds that I might otherwise not encounter—but in terms of being morally ambiguous, I think I'm most interested in characters that are taking a lot of risks and that are acting from a place that is more impulse than thought. These characters are often muddled by addiction and poverty and by systemic things in their own generational lineups that have set them up for this moment. I tried to show how they got there.

I can’t think of any books that I love where the characters are acting from a moral position all the time. In almost every book I love, the characters are unhinged and on their last dime. I’m interested in what people do in those desperate moments. It offers us a moment to ask ourselves, “What would I do?”

Was there a story that especially surprised you?

The most surprising story for me was the first one, which is called “Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Miners.” This one was born out of this material that I found going through my mom’s storage unit when I was 24 or something.

I found some of her writing, some of her community college assignments. She wrote this incredibly interesting and funny and really well-written narrative essay about miners, because my dad was a miner. The last line was, “Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be miners.” She got a C minus on the paper because she didn’t really follow the directions, but if I had read that paper as the professor, I would have been like, “Hey, you should keep writing. You’re really good at this.” I was so struck by the language that she used and the tone. It was just a side of her I didn’t know existed.

What other things inspire you?

For me, language is just always first: the sound of the way someone is talking, a strange turn of phrase, a funny way of explaining something. My mom was really the original storyteller—I think it was ingrained in me. I grew up in a really chaotic environment, and a lot was going on, a lot of “unbelievable” things seemed to always be happening. That’s what the life of a child of alcoholics is, like you’re living in this alternate universe. My life is so boring now [laughs]. I would never encounter those scenarios now, but they’re in me still. Godshot and this book are really evidence of that.

I'm also inspired by other local writers here. I would love to give a plug for Chris Stuck. His collection of stories, Give My Love to the Savages, was so beautiful. And Emily Prado, who wrote Funeral for Flaca; Kimberly King Parsons of Black Light; and Genevieve Hudson [author of Boys of Alabama]. I feel really lucky to live in this community of so many amazing writers. We all know, like, the heavy hitters that live here: Cheryl Strayed, Lidia Yuknavitch, the icon. There’s so many. I could name thousands. But there's just a few that I find really inspiring right now.