History Has Its Eyes on Hamilton (and It Isn't Looking Great)

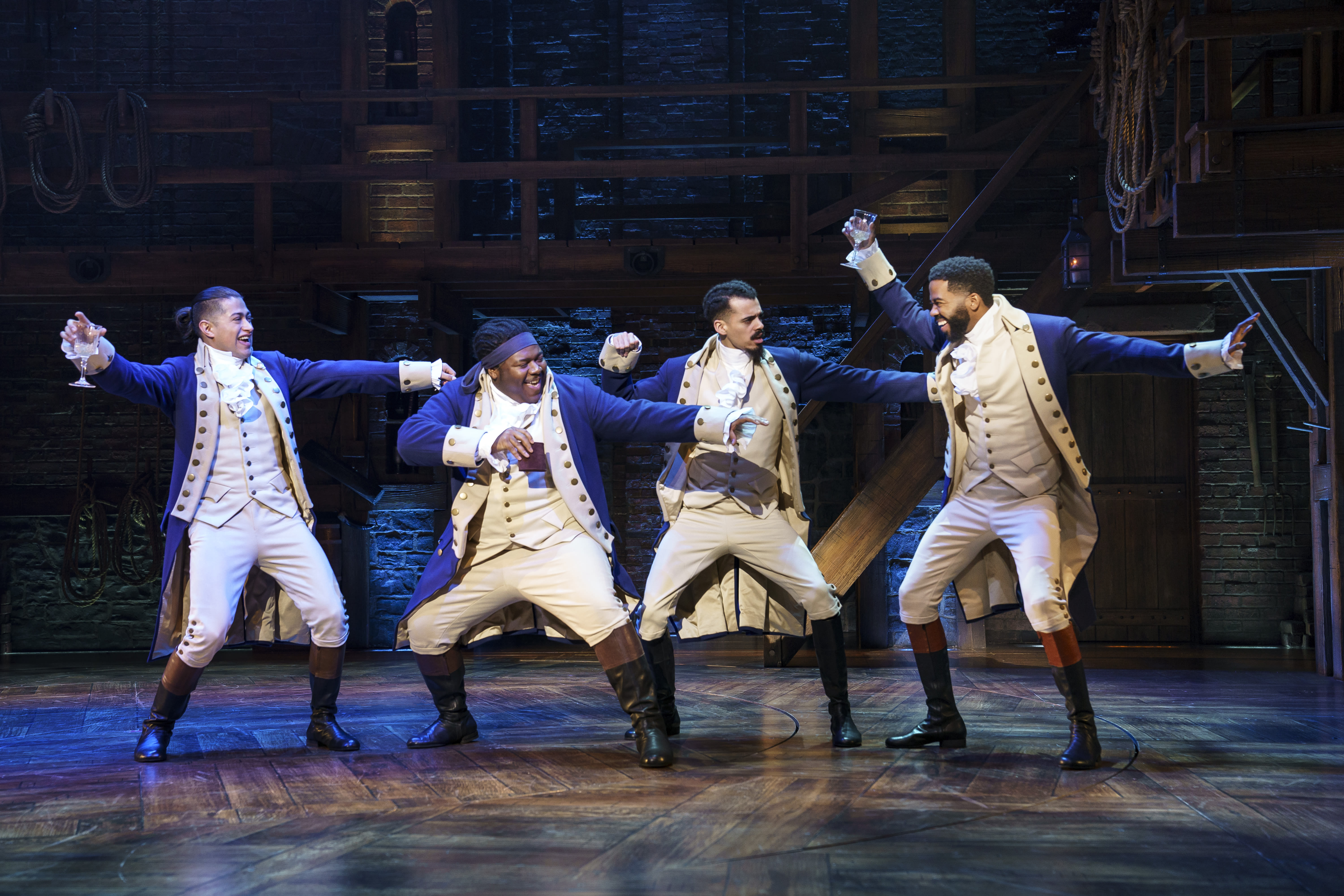

The company of Hamilton

Image: Joan Marcus

There’s something haunted about watching Hamilton in 2022. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Pulitzer-winning smash about the life and times of America’s first secretary of the treasury is only seven years old, but it carries the conspicuous specter of the Obama-era optimism that birthed it. (Playwright Ishmael Reed has been saying as much since at least 2019, when his scathing one-act The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda premiered in New York.) The show’s North American tour arrived in Portland on April 13, and it will hold down the Keller Auditorium for the rest of the month in a nearly sold-out run. You probably already know if you’ll be there.

Indeed, there is maybe no act more Sisyphean than writing a review of the musical Hamilton this many years into its global dominance—the notion that anyone might be agnostic at this point is roughly as insane as asking a stranger point-blank if they “like Adele.” But with distance from the red-hot hype of seven years (and two administrations) ago, it’s easier than ever to clock the show for what it is: an overstuffed, occasionally brilliant book report from the most precocious kid in class. And it’s instructive to consider which of those attributes helped it ascend to cultural juggernaut status.

In case you’re somehow unfamiliar: Hamilton spans from 1776 to the turn of the 19th century, following young upstart Alexander Hamilton (played by Julius Thomas III) and his perennial frenemy Aaron Burr (Donald Webber, Jr.) as they love, lose, and mingle with a host of American revolutionaries. The score and casting are the kicker: it’s a lily-white story told by a company of color, who rap and croon out slick Broadway R&B as they piece together a fledgling nation.

Hamilton is nothing if not studious. Miranda’s score overflows with historical detail and bookish witticisms that literal millions now wield like cultural flashcards; names like Marquis de Lafayette and Angelica Schuyler have entered the popular lexicon almost exclusively on the back of this musical. But the problem with that studiousness is the way it chafes against Miranda’s instincts for human-scale drama. Hamilton ultimately covers too much ground in its frenetic two-and-a-half-hours, and the sporadic infusions of genuine passion (like “Burn,” Eliza Schuyler’s scorned power ballad, or Aaron Burr’s torchy manifesto “Wait for It”) wind up elbowing for space among the too-clever Wikipedia summaries that form the show’s connective tissue.

In the end, for all its staggering rhymes (many of which fly by so fast you might miss them if you haven't studied in advance), Hamilton fails to nail down some fundamental necessities. We never learn why we should care about Alexander Hamilton, specifically—Miranda just supposes we’ll adore him for his ambition—and despite its surface subversions, we're rarely encouraged to think critically about the American institutions being built before our eyes. It’s a show that knows better than to cast white men as our “Founding Fathers,” but not well enough to suppose that those men had flaws more significant than a penchant for social climbing or a light brush with adultery. The few mentions of slavery whizz by without much incident. In 2015, it was easier to take an audience’s fundamental belief in the American experiment for granted; in the harsh light of 2022, catch-phrases like “Immigrants: we get the job done!” sound unbearably facile.

Now, national tours exist to bring musicals to crevices of the country they may not otherwise reach. Theater-lovers—particularly young ones—who have lived and died by the Hamilton cast recording will be rightfully delighted at the opportunity to see it in the flesh without footing a travel bill to New York. And as presented in Portland, there are sparks of real magic: Paris Nix is a hoot pulling double duty as Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson, and Marja Harmon’s Angelica Schuyler is sharp and charismatic (with pipes that bring to mind a huskier Idina Menzel). But there’s something undeniably distressing about the price audiences will have to pay to get in the door: prime orchestra seats, which typically sell for about $120 at one of the Keller’s Broadway Across America engagements, are running a cool $400 for Hamilton. (There is, of course, the ultra-competitive lottery, which offers a lucky few $10 tickets each night.)

Maybe that price tag accounts, in part, for the atmosphere of determined enjoyment in the room. At the performance I attended, the show’s opening lyrics were drowned out by the kind of deafening applause you might expect at a Lady Gaga gig, and early melodies were hummed by scores of audience members who may as well have been home watching it all play out on Disney+. The whole evening felt more like dutiful reenactment than live-wire magic making, and it was often hard to tell whether the crowd was moved more by the quality of the material before them or the thrill of recognition.

The blame for that limpness lies largely with the venue. In New York, Hamilton runs in the Richard Rodgers Theater, which seats about 1,300; a sold-out night at the Keller, on the other hand, packs in nearly 3,000 bodies. The space is such a cavern that it dwarfs its own proscenium, making even some of the $400 seats feel miles away from the action. That distance sometimes causes the stage to register more like an enormous screen, and it encourages a mummified engagement where audience and actors do not exchange anything approaching raw energy.

Still, however remote, the production is plenty competent—it retains the Broadway staging's evocative lighting, and only Rick Negron's King George stands out as a real weak link in the cast (he fails to properly exhume the comic riches in his Britpop park-and-bark numbers). Songs like "The World Was Wide Enough" and "The Room Where It Happens" maintain their virtuosic punch, even if others get lost in muddy blocking. If you're expecting Hamilton, you will get Hamilton, and I don't begrudge you that.

Just don't be surprised if you squirm in your seat a bit and find yourself living out an ironic illustration of one of the show’s central themes: you might break your back to get into the room where it happens, but its contents are rarely as satisfying as you’d hope.

Hamilton

7:30 p.m. Tue–Fri, 1 & 8 p.m. Sat, 2 & 7 p.m. Sun through May 1, Keller Auditorium, $65–400