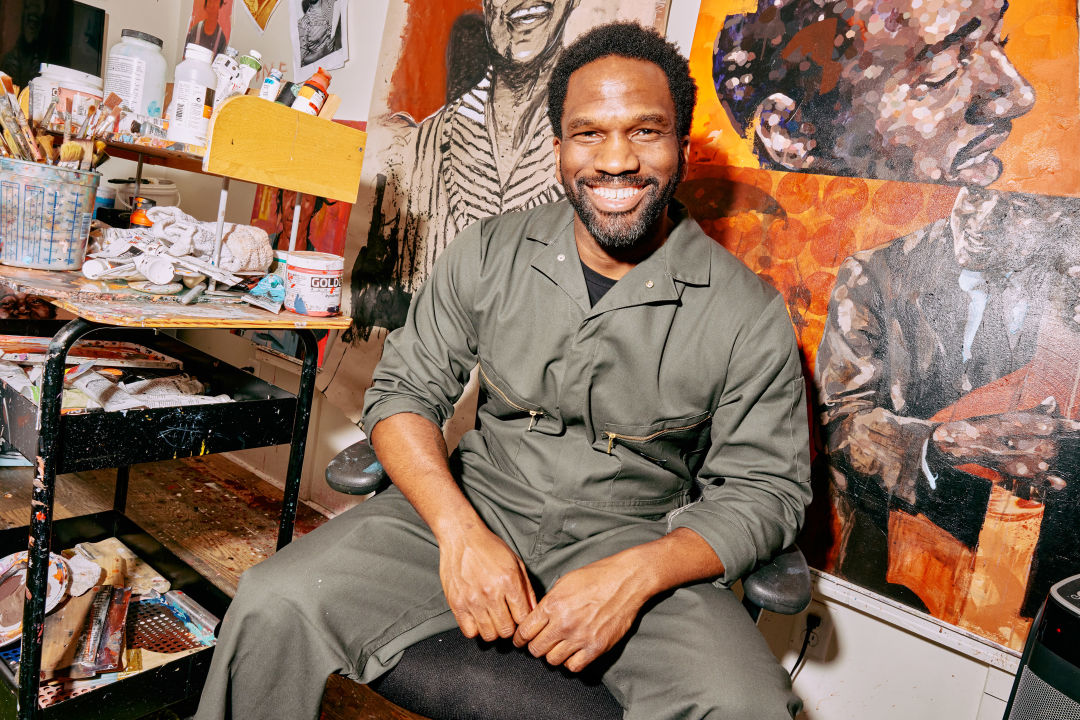

Painter Jeremy Okai Davis Doesn’t Sleep Much

Jeremy Okai Davis in his backyard painting studio

Image: Michael Raines

Jeremy Okai Davis’s partner, Brittany, recently bought him a pair of forest green Dickies coveralls. “I wanted a uniform,” he says, to help draw boundaries between his graphic design day job, his busy life fathering their two sons (ages three and five), and the hours he sneaks out to his painting studio in the backyard. When he’s in the suit, Davis says in an assuredly calm baritone that still carries a touch of his North Carolina roots, “I know I’m working.”

As a portrait painter, Davis, 44, uses a form that’s been relatively outmoded by photography. He paints ignored or otherwise thwarted Black historical figures (musicians, actors, pioneers, and athletes), giving them their belated due in a distinct, pointalist style—think pixelated images rendered with painterly textures. His acrylic paintings have hung in the Studio Museum of Harlem, in New York; at THIS, in Los Angeles; and are in permanent collections at both Oregon State and the University of Oregon.

His backyard studio is beginning to fill with paintings for his third solo show at Elizabeth Leach gallery in Portland, scheduled for September. Meanwhile, he’s also curating a group show devoted to mixed-media works (featuring artists Rebecca Boraz, Maria Britton, Anthony R. Grant, and Chris Lael Larson), Mélange, which opens at Nationale February 24.

How might one person pull all these threads together? He doesn’t sleep much. A treadmill, a healthy Blazers fandom, and blurred boundaries enable the rest.

Describe your studio.

It’s comfortable, almost like a living room. There’s a TV—I’ve always watched movies while I work. And I want it to be kind of a mess. I keep the same mess [as I’m making] a body of work: works in progress, inspirational pictures pinned to the wall, books I’m working from are out and about. It’s organized confusion. I want it to be set up when I get in here.

What’s the most impractical but crucial thing you keep here?

Probably the treadmill. If I’m starting to get tired late in the evening, I get on there and jog or walk for a bit—like you’d walk around the neighborhood. It helps process things. I’ll zone out and start thinking about my next step on a piece.

What gets you in the right headspace to work?

Deadlines. Necessity. I have to make the work; I have to be in the right headspace, so I just bring myself to the studio and put myself there. To stay in that headspace, jazz helps with backgrounds; podcasts and movies help with detail work.

Give me the bullet points of a typical workday.

Monday, Wednesday, and Friday are the days that I’m home in the studio, and not at the office. I wake up, take the kids to school and daycare, and get back at 8. I give myself a 30-minute window to check in with work, then I close the laptop and don’t open it again. Then painting, reading, anything centered around my art practice. After lunch, another 30 minutes on the laptop. Close it again. Then I’ll work until 4:30 or five, when the kids and my girlfriend get home. If I have the energy for it, the evenings still feel like the best time to make work. Sometimes I’m out here pretty late—till 1:30 or two o’clock.

How many hours do you sleep?

Six at the max. Three if I’m in the throes of a body of work.

What are you obsessed with?

Up until a couple years ago, I didn’t miss many Blazers games. I would sacrifice studio time. Even if I had a project to do, I would go to a bar with friends to watch a game.

Describe being an artist in America.

Foolish. It’s that age-old thing: why would you choose this? But it’s also empowering, to have this outlet to take in all the negative, the positive—all the things—and throw them back at people in a creative way.

Image: Michael Raines

Why did you want to curate a show?

I used to have a highly curated Tumblr page, where I [posted] things that inspired me. Curating a show, in a sense, is like that in real time, in the real world. Trying to curate a show that feels cohesive, that makes sense and looks good on the wall, makes me consider the work that I’m making. It’s inspirational for me. In a way, it selfishly gives me the opportunity to slip into other artists’ studios and see what they’re doing.

Why did you want to show collages?

I was interested in the idea of a show that speaks to painting without having actual paintings in it. My work doesn’t outwardly reference collage, but I am collaging ideas and images in it. I’ll often start with a Photoshop “collage,” or a physical collage, that I’ll then draw and transfer to a painting. The show is, like, “the steps to a painting,” in a way.

What was the last great show you saw?

The Black Artists of Oregon show at PAM [through March 31]—save the fact that I’m in it. Intisar Abioto curated a show of Oregon-based Black artists. But it’s not just about being a Black artist. It’s multifaceted. There’s an idea that all Black people see things the same way. She did a great job presenting the Black experience from many angles. Some of the work isn’t even about the Black experience; it’s just about the experience of being a person or an artist in the world.

A show you’re looking forward to?

I love Laurie Danial’s abstract paintings; she shows with Froelick Gallery and has a few paintings in its current group show (through March 2). I love portraiture, people, figures. But I sometimes think about throwing all that out the window—what it would be like to let the paint be the thing that people respond to. And she does that.

What inspires your work beyond visual art?

I played the Seattle folk singer Dean Johnson’s album into the ground the past couple weeks [from Portland’s Mama Bird Recording Co.]. His music sits in this old, folky feeling, but somehow feels contemporary, like it was made right now. In my paintings, I reference the past—art history, historical figures—but bring it into the present, and try to make it interesting for all people. Maybe that’s why I like Johnson so much.

Image: Michael Raines

One Portland-centered piece of art that everyone should know?

There’s a mural of “Working” Kirk Reeves [the beloved street performer who died by suicide in 2012] on NE Grand, on the side of the Dutch Bros. I would see him every day on my way home from work, on the downtown onramp for the Hawthorne bridge, playing instruments and doing magic tricks. He was struggling with his mental health, but he was always there, wearing these Mickey Mouse ears, trying to make people happy. I’d wave, but I never spoke with him. Thinking back: What would talking to that guy be like? What’s his story? What was his life like?

If you could have coffee with one dead Portland artist?

I remember seeing one of Henk Pander’s pieces at the Portland Art Museum when I first moved here and wondering, “What amazing, art-historical person made this work?” Then I learned he was alive and working in Portland. But I never met him. If I had met him earlier, I would have asked him, “How do you get to the place you are?” But now, I think I already know that there’s no such thing as getting to that place.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.