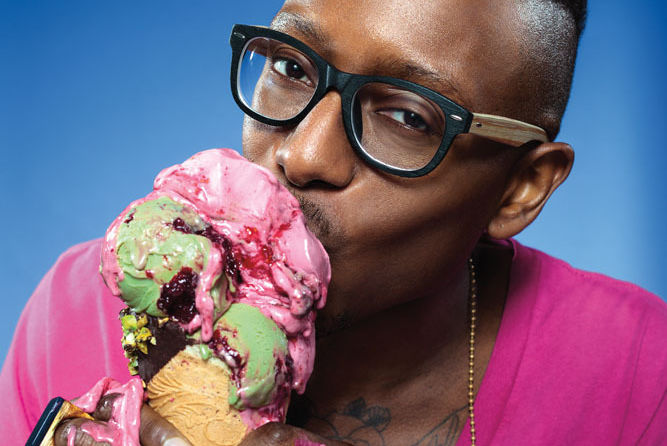

The Voracious Appetites of Chef Gregory Gourdet

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Chef Gregory Gourdet is stuffing his face with vegan ice cream sandwiches. Four hours ago, the mohawked beanpole was lifting weights in a chilly Northeast Portland gym; 36 hours ago he was running 12 miles up the side of Mount Tabor; 12 days ago he was trading recipes in Austin, Texas, with two dozen of the nation’s rising chefs; three weeks ago he was dancing through the Caribbean on an electronic music party cruise. “I tend to overdo things, good and bad,” he says.

But, at this moment, 48 hours before he’s slated to feed more than 300 of the city’s food world insiders at the third annual party he calls simply “Salon 3.0,” the chef de cuisine of downtown’s sky-high Asian restaurant and lounge Departure stands, however briefly, in one place. There’s the messy job at hand of cramming a melty gob of coconut–cashew brittle ice cream smooshed between two miso-butterscotch cookies into his maw. He nods thoughtfully as he chews. “Can you add more miso?” he asks one of his chefs, giving the sandwich a thumbs-up to be served at Salon before making another one disappear. “I have a huge sweet tooth,” he mumbles. “Huge. Huge.”

Gourdet, 37, wants more, constantly—blasting away his limits physically, socially, and gastronomically while freely challenging the city’s idea of what makes a Portland restaurant and chef, well, “Portland.”

Departure's bibimbap with koshihikari, Wagyu beef, egg, kimchi, and gochujang.

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

When the soft-spoken New York native took over the Nines hotel’s astro-sleek 15th-floor restaurant in 2010, it was better known for its hard-partying bridge-and-tunnel singles scene than for its eats. In three years, he’s turned the dining room into a lively hub for creative, pan-Asian cuisine, a spot where Oregon’s produce, meats, and seafood are transmuted into bold yet comforting dishes that sizzle and pop with the big, bright flavors of chile, lime, and ginger. Visiting the restaurant is an expensive but giddy-making surprise: it’s as if you went into a dressing room to try on a pair of gaudy Ed Hardy jeans and came out clad in an Armani suit.

Like Roe’s micro-luxe seafood operation or Castagna’s modern experiments on the “dish” and “meal,” Gourdet’s big city–style kitchen is restlessly challenging the trope that Oregon’s bounty speaks best for itself. “I think we can do more interesting things with the amazing ingredients that we have,” he says. “I enjoy eating a roasted beet salad, but I need a little bit ... more. I want to keep pushing to make food that keeps you awake.”

Beyond the food, Gourdet himself has become a Portland restaurant community touchstone. Plenty of chefs champion local farms and food-related small businesses. Gourdet is a booster for everyone else, too, the kind of guy who also organizes fitness challenges for his fellow chefs on Facebook and throws free parties to celebrate the whole scene—chefs, servers, food vendors, and other insiders. “They’re ridiculous. Nobody does that kind of thing,” says St. Jack chef-owner Aaron Barnett, who first met Gourdet in 2008. “He works his ass off.... He goes out of his way to try actively to be Julie from The Love Boat and get everybody together to hang out. He’s becoming the cruise director of Portland food.”

“I just think it’s important to connect,” says Gourdet of all his parties, farm visits, Bikram yoga dates, tweets, and Facebook posts. One of his New Year’s resolutions was to get at least six hours of sleep a night. “I’m already fucking that up,” he says.

It’s as if he is addicted to Portland. And Gregory Gourdet knows what addiction is.

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Charcoal hair standing in a tall, square-cut tuft with a blond wisp running through it, eyeglasses as big as a teacups, and—when he’s not clad in his chef whites—maybe a bow tie or a pair of studded motorcycle boots, Gourdet makes the average mustachioed Portland hipster look like a West Burnside hobo. And he cooks like he looks.

From 11 a.m. to 2 a.m. most days, he camps in the kitchen at Departure, orchestrating the movements of more than a dozen chefs, from a sextet of prep cooks snipping the tips off 500 chicken wings to six to 10 line cooks (depending on the season) and a pair of trusted sous-chefs. On this Friday afternoon, they are all busy preparing for dinner service and simultaneously prepping 21 separate dishes for Sunday’s Salon 3.0, from yuzu gel–laced kampachi nigiri to fiery chicken adobo. Still, his kitchen is calm and remarkably quiet, a symphony of rocking knives, clinking dishware, and clanking pots. Gourdet may never miss a party, but he’s all business during work hours.

In between tasting cookies and holding powwows with his team, he’s whipping up an omelet for himself that’s bursting with smoky red chiles, spinach, red onions, and garlic. “I’m very much a line cook at heart,” he tells me, drizzling a puckery soy vinaigrette spiked with fish sauce and lemongrass on top. “I’ve had to learn to delegate. I have faith in my chefs.” He needs to: with 150 seats, Departure has one of the biggest dining rooms in Portland. The fast-paced kitchen serves up to 400 people a weekend night during the busy summer season—that number can skyrocket to 800 when you count bar patrons and revelers sipping cocktails and posing for photos on Departure’s mod, cruise ship–style patios.

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

With its angular architecture, glowing Tron-like entrance, and dramatic view of the city, Departure feels airlifted from Las Vegas, impossibly out of place in a town in love with wood-fired ovens, exposed beams, and casual nights out. But Gourdet grounds it firmly in Oregon ingredients, from the Carlton Farms pork belly braising in a pair of giant sous vide machines to the DeNoble’s Farm kale for the roasted squash and goji berry salad. The kitchen’s pantry shelves are packed with local nuts and seeds. Last summer, the staff juiced and froze three cases of Mountain Rose apples during the three-week window when the rare Hood River fruit was available. They used it to sweeten fall sorbets. “I have a little, secret desire to be a farmer,” Gourdet admits.

His crew revels in the kind of labor-intensive techniques and personal touches you often find at boutique, chef-driven spots around town, from making their own spicy XO sauce and Thai sausage to dehydrating Oregon shrimp for a fiery fried rice. The cooking—and, of course, his eccentric, flamboyant personal style—earned Gourdet a spot on Food Network’s loopy Extreme Chef in 2011, where he jumped hay bales and ran through a dust storm before preparing dishes for a panel of judges. He won top honors at the Great American Seafood Cook-Off in New Orleans in 2012, snatching victory from a field of 16 chefs from across the nation with a slow-cooked Oregon chinook salmon with bacon dashi and pickled porcini. This year, the Oregon Department of Agriculture named him Chef of the Year (“I was touched,” he says of the state’s somewhat nerdy honor. “I totally cried when I got the news.”). He also won Eater Portland’s “Hottest Chef 2012” award—a title that just makes him giggle.

Thus far, the James Beard nominations and New York Times stories that have vaulted some of the city’s tiny, chef-owned eateries to American dining’s top echelons have yet to “discover” Gourdet. It may take a while. Portland is a city that loves (and is beloved for) its plucky, shoestring operations and gutsy, gluttonous dishes. A glitzy hotel restaurant bankrolled by out-of-towners doesn’t fit that mold, regardless of how many meringues its chef whips up from foraged Oregon-coast seaweed. But Gourdet’s not worried. “We’re not at the top of the list for classic Portland restaurants yet. The older foodie generation references Beast and Le Pigeon and Pok Pok. I think a younger generation will reference Departure.”

Famed Pok Pok owner and James Beard Award winner Andy Ricker agrees: “I really feel like the food at Departure is some of the most undersung in the Portland milieu,” he gushes via e-mail from Thailand. “[Gregory’s] a fiercely creative chef and is making food that is as decidedly ‘un-Portland’ as the restaurant he does it in ... which of course makes the whole thing soooo Portland.”

“I left New York chubby and kind of broken,” Gourdet says of his pre-sober days.

Born to a pair of Haitian immigrants in Queens, Gourdet says spice and heat are his first food memories. “There was always a jar of pickled Scotch bonnet peppers on the table when I was a kid,” he says. Playful notes of hot, sweet, and sour remain a hallmark of his cooking, making for dishes that look modern and elegant on the plate but detonate like wild flavor pyrotechnics on contact with your tongue. The unassuming sweet mayo hiding under his crisp-edged scallop, pork, and shrimp pancakes is pumped up with puckery vinegar powder and pickled shallot juice. His standout pork belly is the product of a two-day kitchen affair: grilled, marinated in hot sugar ginger chile sauce, cooked sous vide for 24 hours, pressed into blocks overnight, and then flash-fried crispy. It’s paired with good olive oil and blush-colored orbs—addictive jalapeño-pickled cherries. Each meaty cube dissolves in your mouth, leaving the flavors of creamy fat, spicy-sweet crystallized ginger, and nutty pepitas behind. If you don’t like the burn, don’t bother sitting down—Gourdet even sneaks chiles into desserts. The spiced tapioca cup layers chewy pearls with shards of coconut ice, cilantro-mandarin sauce, and cubes of fiery Thai chile–laced pineapple, all sprinkled with Oregon’s own Jacobsen salt.

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Gourdet honed his culinary style during six years working for Jean-Georges Vongerichten in Manhattan in the early 2000s, an era when the influential chef’s constellation of French- and Asian-tinged restaurants was setting the New York dining scene afire. But Gourdet says he gets his work ethic from his parents, who managed hospital chemistry labs while he was growing up. With the help of scholarships and financial aid, they sent their son to a Delaware boarding school. “Have you ever seen Dead Poets Society? That’s my high school,” he says. He tried on premed at NYU and wildlife biology at the University of Montana. “I realized I wasn’t that outdoorsy,” he laughs. In the Big Sky State, he caught the food bug, working at a vegetarian sandwich shop and a high-end bistro to pay rent.

After graduation (he ended up with a BA in French), he applied to the Culinary Institute of America in New York. “It just clicked,” he remembers. Two years later he was on the line at both Jean-Georges and its café Nougatine in the Trump Hotel & Tower. He steadily moved up through the ranks, station by station, until he became chef de cuisine of the restaurateur’s high-end Asian spot, Restaurant 66. He says it was 66’s staff of “real Chinese guys” who taught him how to use a wok and prepare dishes like the succulent, “extremely labor intensive” Peking duck that sells out at Departure every December.

But New York taught Gourdet much harder lessons, too.

In the mornings, before he bikes downtown to start his shift at Departure, Gourdet can be found running trails in Forest Park or heaving iron and climbing ropes at the cavernous training gym CrossFit Portland. As he strains to perform a series of complex moves with a barbell, over and over again, he still manages to look a bit the dandy, in a teal T-shirt and tall black athletic socks. “I hate lifting weights,” he admits after class, a bit preoccupied with the high number of RSVPs that are coming in for Salon (300 and counting so far). But weight lifting, along with a battery of other physical challenges, keeps him fit, lean, and, most important, centered. It wasn’t always this way. Gourdet claims Portlanders wouldn’t recognize the New York chef he once was: “They’d be, like, who is this chubby asshole smoking cigarettes and yelling at me?” he says, with a nervous titter. “I was really irresponsible and careless.”

That’s Gourdet’s shorthand for his seven-year battle with cocaine and alcohol. Born in part from late nights with his NYC kitchen crews, it’s a story that plenty of line cooks and bartenders would recognize. “I was party-party-party. Mr. Popular. I spent all my money as soon as I got my paycheck,” Gourdet says. “It led to falling-outs with friends, bad relationships.” He points to the long, faint scar between his right thumb and index finger. “I grabbed a hot pan full of hot oil,” he says. “I was half asleep.”

Gourdet went to rehab in the summer of 2007. One month later, after a move to San Diego, he started binge drinking. “I got in a car accident. I got arrested a couple of times for public drunkenness,” he lists. He moved again in 2008, this time to Portland to take a job as chef de cuisine at the then-new Nines hotel’s Urban Farmer restaurant, a few floors below Departure. He left four months later, not ready to commit to the structured lifestyle a big hotel operation demands. He ended up running the kitchen at Bruce Carey’s swanky downtown cocktail bar Saucebox instead. “I wouldn’t drink for a week, and then I’d go to my friend’s bar and we’d stay up until 8 a.m. drinking and doing coke and smoking pot,” he remembers. “I had this person in my head that I wanted to be, and this wasn’t it.” He eventually tried AA at the urging of a fellow chef. It worked. “That was four years ago in March. Done deal.”

Gourdet ran his first marathon seven months later, replacing his booze binges with workouts—and, he laughs, the occasional drag dance party in his living room. He’s still pushing his limits (still staying up all night, still overextending himself), but now it’s to train, not to attend the after-after-party. He’s competed in eight marathons since 2009 and is planning to run four more this spring, including a 50-kilometer ultramarathon in Winthrop, Washington, in May.

In 2010, Departure’s owners, Sage Restaurant Group, began scouting for a chef. The company’s corporate chef remembered Gourdet from Urban Farmer and sought him out. Offered another chance to helm his own big, New York–style hotel restaurant, this time Gourdet leapt at it. Since then, opportunities to run his own smaller operation have come up, but he’s declined. “I like excitement and things on a much grander scale,” he admits. “I want to see what Departure turns into in the years to come. I want longevity and focus. I want to be something people can count on.”

He pulls down the collar of his white chef’s jacket to reveal a wide arc of cursive letters tattooed across both of his collarbones. Borrowed from Shakespeare, it’s one of AA’s mottos: “To Thine Own Self Be True.” A big rose blooms in the middle of the inscription, right on his sternum. “I know,” he says, half embarrassed, half proud. “It’s very Portland.”

Fast-forward through his morning CrossFit workout and past a full day’s worth of meetings, planning sessions, and ice cream sandwich tastings, and Gourdet is finally back doing what he considers himself best at: cooking. Departure is open for dinner, and the head chef is on the line with his team, stir-frying brussels sprouts—an addictive, zingy bit of vegetal heaven, heavy on fish sauce, lime, and mint. Gourdet loves them, and in two days he will serve a vegan version of the dish at Salon for his abstaining patrons. “They’re better with the fish sauce,” he sighs, “but making them vegan is important.”

While other chefs grumble about customers’ dietary restrictions, Gourdet has taken Portlanders’ nutritional demands as a challenge, adding extensive vegan and gluten-free menus at Departure. “From a culinary perspective, it just makes you think differently about what you can use to cook,” he says. “It’s important to feel the pulse of what’s going on here and react to it. It’s a global change. It’s about environmental consciousness. People are more concerned about cancer and allergens and, really, just feeling sick. So, they are concerned about what they eat.”

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

The chef himself is on the restrictive paleo diet, which cuts out dairy, grains, and legumes in order to re-create the kind of “caveman” cuisine hominids enjoyed for 2.5 million years of evolution before we started raising our own food. “I think people think I’m crazy,” he laughs. He threw Departure’s first special paleo dinner in March.

Around 8:30 p.m., a server delivers a small package for Gourdet as the chef stands eyeballing the fragrant dishes coming off the line. It’s a surprise: a bow tie from Pino, a local menswear company. The note, from Pino owner Crispin Argento, says he thought the chef might like the custom-made silk grosgrain accent to wear to Salon. Gourdet just smiles and slides over to a chatty server who has paused, hot dish in hand, to talk to a line cook. “Go,” he says softly, arching an eyebrow and jerking his head toward the dining room. “Go-go-go.”

One of his two sous-chefs, Benjamin Love, is standing at a nearby butcher block scooping balls of rice dough for date-filled sesame mochi. “He befriends them,” he says of Gourdet’s highly effective management strategy. “It’s better than yelling.”

Tidy as his restaurant kitchen, Gourdet’s Northeast Portland bungalow features a cow’s skull with gold-leaf horns in the living room and a rainbow of more than 100 pairs of Nikes and high heels in his bedroom. The paper numbers he wore during each of his marathons are tacked in a vertical line next to his bed; on the other side hangs a cheap little plastic crown emblazoned with the words “DRAMA QUEEN.” Standing at the kitchen counter, still bleary-eyed from his late night at work, the chef is trying to shove a carrot down the mouth of a shiny silver juicer. The machine groans and whines, producing a tiny trickle of orange liquid for the chef’s morning energy drink. “This is why you never buy a juicer online,” he mutters.

Gourdet, who is gay, says he’s too busy to date much. Instead, he shares the house with Tia Vanich, his “sassy bestie” and one-woman cheering squad. The pair formed a deep bond after meeting in AA in 2009 and later working together at Bruce Carey Restaurants. Vanich, who produces festivals and events for the music and food world, is also a guiding force for many of Gourdet’s parties, including Electric Summer. That’s the eight-hour, DJ-fueled rager the pair threw for 400 of their food and music industry friends at Rontoms last August, complete with eats from Nong’s and Podnah’s Pit, Jell-O shots, and costumes. Vanich and Gourdet spent $5,000 of their own money to put on the event. Guests didn’t pay a penny.

“Portland’s not a city that stays sober—especially in the restaurant industry,” Vanich says, struggling to explain why she and her best friend go to such lengths to celebrate their community. “He’s a special case. Being in recovery is a huge reason why he is the way he is. You’re excited about life again ... you don’t have any fear anymore. We’ve gone to hell and back. When you’ve done that, why not throw a huge party?”

The next evening, he does. Salon 3.0. is packed; you can’t walk two feet without brushing up against a person who has grown, distilled, baked, or cooked something you’ve eaten in the past two months. Gatherings like this happen elsewhere, but usually with well-heeled foodies paying top dollar to attend and the chefs serving samples. Here, everything is free, and the guests who spend their lives serving food have the night off. Sage Restaurant Group closed Departure to the public for the night, agreeing with Gourdet that it was an opportunity to give back to the community—and to show off the restaurant’s chops.

The chef is sporting that Pino bow tie and a silver lion’s head belt buckle as big as a coaster. Later on tonight, he’ll be at an “insta-dance party” at Dig A Pony, singing and bouncing along to TLC’s “What About Your Friends” with 60 of his nearest and dearest; six days from now he’ll be charming fishermen’s wives at the Portland Seafood & Wine Festival; by next week he’ll have run another 50 miles of Portland pavement and trails.

But, for now, he’s where he’s been for most of the evening: standing near the tunnel-like entrance of Departure, greeting friends—which at this point seems like half the city—a lanky dot of calm in the middle of a music-fueled melee. A server whizzes by with a tray full of those vegan ice cream sandwiches, and Gourdet stops him. “Have you had one of these?” he asks me. “Have another,” he urges in his trademark soft mumble, a big grin splitting his face. “Just have ... more.”