What If a Vaccine Comes to Oregon and No One Gets It?

We’re all waiting for a coronavirus vaccine. Or are we?

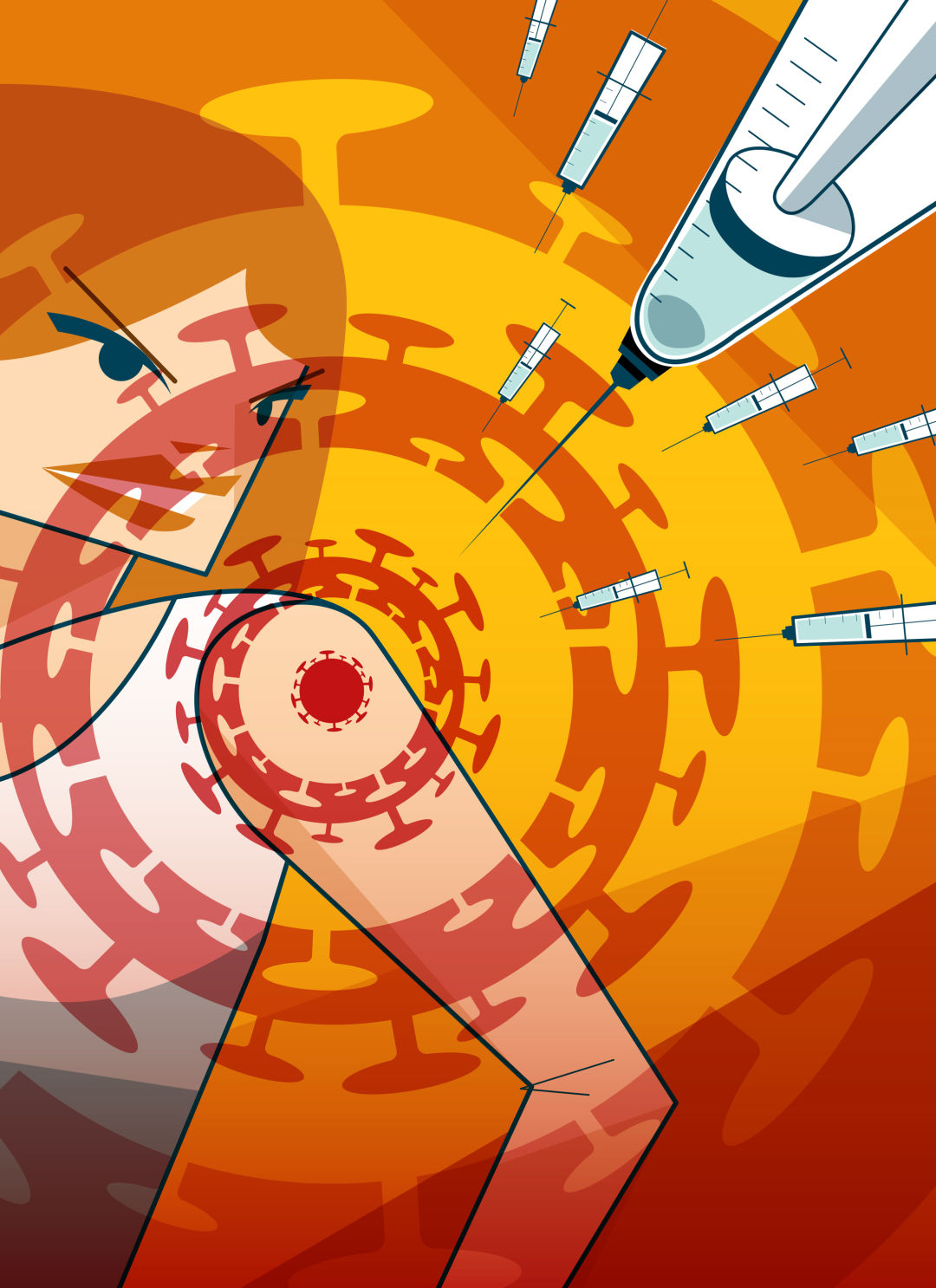

Image: Martin Gee

Day by day, month by month in this most extraordinary of years, we’ve seen our collective normal slip away—the routine hugs and handshakes, the jostle of the Timbers Army, kids scuffling shoulder to shoulder in a school cafeteria, all of it replaced by uncertainty.

Against this backdrop flares a steady drumbeat of supposed hope: a vaccine, an accelerated race the world over to find the formula that will allow the globe to regain its footing. Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases tells us one might, just might, be ready to go by the new year, and our ears perk up. Maybe there can be normal again.

But the Portland area, and Oregon in general, is particularly fertile ground for the vaccine averse. A loose coalition crystallized after the local measles outbreaks of 2019 and successfully lobbied lawmakers to preserve a parent’s right to opt school-age kids out of vaccines for religious or philosophical reasons. That core movement bridges the political divide between far-right science skeptics and far-left earth mothers. Now the accelerated timeline of the COVID-19 vaccine is drawing in even those who dutifully get a yearly flu shot.

Which prompts the question: What if scientists make a vaccine, and only half of us agree to get it?

Michele Ray, a Portland-area parent with a 12 and a 10-year-old, says she is agonized by the contraction of her children’s lives since the pandemic hit in mid-March, canceling her daughter’s Magic, the Gathering–themed birthday and their long-awaited school science fair, restricting their adventures to the backyard—save for a single snatched trip downtown for shave ice, eaten in the car, windows closed. And yet Ray, who stopped vaccinating her children after she says one of them was injured, says she’s prepared for her family to hunker down at home—indefinitely—rather than get a coronavirus vaccine.

“Somebody is going to have to be the guinea pig, and I think, ‘Well, it won’t be us,’” she says. “And that is not an OK place to be at all. It is beyond not OK that other people are in a situation where they won’t have that choice.”

In forums like those run by Oregonians for Medical Freedom, an advocacy group for the vaccine skeptical, there’s hand-wringing over whether the coronavirus vaccine, should it materialize, might become mandatory if you want to board a plane or work in a public school. It’s a new frontier in the vaccine wars, which have been focused on schoolchildren in the past.

“It’s an individual choice to decide whether to receive or decline this vaccine,” says Bob Snee, who sits on the board of Oregonians for Medical Freedom. “We should not be deprived of our rights to travel, go to school, go to work, if we choose to skip a vaccine with a lot of unknowns about its safety.”

Such doubts are not unique to Oregon. An NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll in August found only about 60 percent of Americans say they’d be willing to get the vaccine, even as different companies race toward the finish line, abetted by a $10 billion public-private partnership backed by the US government, dubbed Operation Warp Speed.

In Oregon, 93.1 percent of schoolchildren were up to date on all vaccines as of 2019, according to the state health authority, a figure that drops to 92.7 percent in Multnomah County. Scientists say that upwards of 94 percent of a population needs to be fully vaccinated in order to achieve herd immunity.

Low rates are terrifying for parents like Jessica Fichtel, who lives in Vancouver and whose son, Kai, is in remission after battling acute lymphoblastic leukemia. “I am vicious with people when they refuse to acknowledge that their choice not to vaccinate could kill my child,” she says. “If it is approved and safe, our family will be vaccinated. Kai will get it based on the discretion and direction of his medical team at OHSU. I hope enough people will shoulder the burden, like they always do, to help us move towards some sort of herd immunity.”

That herd immunity message is foremost in the mind of Nadine Gartner, a Portland parent who founded Boost Oregon, a group that aims to puncture myths and educate parents about the safety of childhood immunizations.

Gartner acknowledges the science is moving fast, but she stresses the accelerated timeline doesn’t undermine the scientific rigor the vaccine will undergo.

“What’s different in this case is that usually, money is not put toward the mass production of a vaccine until it has achieved all the different levels of efficacy and safety measures,” she says. “That is not being sacrificed. It’s about spending the money that’s necessary for mass production immediately, as opposed to having a lag.”

It will be up to the Oregon Health Authority—already straining to manage the unholy demands of an unpredictable pandemic—to manage the messaging around a coronavirus vaccine.

To start with, says communications director Jonathan Modie, the agency will double down on persuading Oregonians to get this year’s flu vaccine, to hopefully keep down the numbers of flu patients in area hospitals should coronavirus spike in the fall and winter.

Even that is an uphill battle: in the 2019–2020 flu season, only 36 percent of Oregonians between the ages of 18 and 39 got a flu shot.