An Innovative Recovery Center Breaks Ground in East Portland

Image: Courtesy Ankrom Moisan

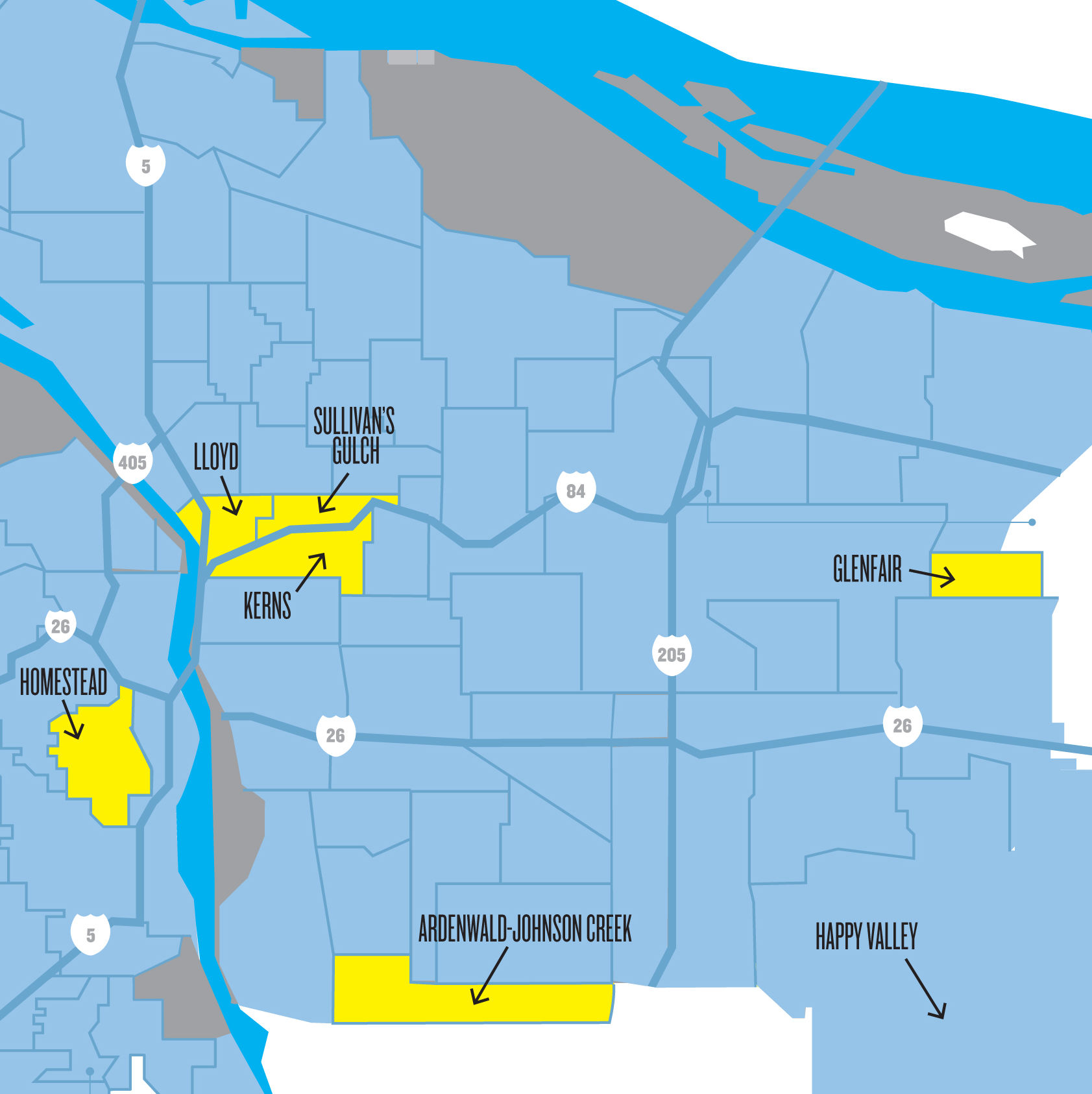

Central City Concern, the nonprofit that has aided Portlanders dealing with houselessness and addiction since 1979, decided to do a little research. Over the past few years, the organization created a heat-map-style chart, showing the zip codes of people who checked in at its flagship Old Town facilities. “This is the first time, in our 40 years as an organization, that we’ve made the investment in technology to interpret raw data that way,” says Central City’s Sean Hubert.

They found need rising in the east. Recession, gentrification, and demographic change meant that many Central City clients trekked in from Portland’s outer east side.

Last fall, CCC broke ground on its new Blackburn Building, a substantial nest of housing, recovery, and medical care at E Burnside Street and NE 122nd Avenue. Funded in part by major local hospitals and health care companies, the new center will bring social services traditionally concentrated in the city’s core to a fast-growing, oft-neglected section of Portland.

“In the ’70s, homelessness was most acute in downtown Portland,” Hubert says. “That’s not the case anymore.”

The Blackburn—the name honors Ed Blackburn, recently retired after decades leading Central City—will minister to several needs. A medical clinic will offer some primary-care services; on-site housing will include both transitional and permanent units for people in various stages of addiction recovery. By the reckoning of its designers at the architecture firm Ankrom Moisan, it will be only the fifth such overarching facility in North America.

“The neighborhood has been very supportive from the first time we discussed the design,” says Mariah Kiersey, the Ankrom principal managing the project. “They know these populations are there. Design-wise, it’s an interesting environment: commercial car dealerships on one side, single-family housing on the other.”

The stylistic solution: a gable-roofed arc intended to evoke an archetype. (“Ask a kid to draw ‘home,’ and that’s what they’ll draw,” Kiersey says.) The architects staggered sections of the block-long six-story form, both to create opportunities to let in natural light and to carve out distinct areas for different—and often necessarily separate—uses. (Residents of the “clean” housing units will use a different entrance than clients in early stages of recovery, for example.)

“Uniting all these programmatic elements is definitely the challenge,” says design principal Michael Great. “We know the programs will do a lot for the neighborhood and the people Central City serves—we needed to make sure the architecture does something, too.”

The larger hope is that the design proves to be more than a metaphor.

“If you combine the right combination of clinical, recovery, and jobs services with very low-barrier transitional housing,” Hubert says, “you can improve people’s resiliency to homelessness over the long term.”