What Will Portland Look Like in 2035? The City Is About to Decide.

The Pepsi complex just off NE Sandy at 25th shows that in 1962, even a soda depot could flash design pizzazz. The arched checkerboard façade and vaguely Japanese landscaping still lend faded Jetsonian class to rumbling semitrucks, slate-gray walls, and razor-wire-topped fences. But a fresher brand of cool has arrived nearby, via microrestaurants, boutiques, cannabis shops, and design agencies. In Portland in the 2010s, what happens next will not surprise you.

Last August, PepsiCo sold the 4.7-acre “superblock” to Seattle developer Security Properties and a Chinese investment group called Beijing Jade. Recorded price: $27 million. Future plan: a cluster of housing, retail, and office space. “The size gives us scope to develop this over time,” says Security’s John Marasco. “We can plan our own streets, our own open space.”

They’ll have a little help.

New stuff built, old stuff gone, neighborhoods changed, once-sleepy streets and low-rise lots transformed. These current Portland themes often play out to an undercurrent of angst. If you feel that angst (or even if you haven’t yet), steel yourself. About 621,000 people live in the city of Portland right now. Current city projections suggest that over the next two decades, we’ll add about 221,000 more.

What does Pop. 842K look like? We have a rough sketch, in the form of a half-inch-thick book of rules: an exquisitely boring and existentially vital city planning document called the 2035 Comprehensive Plan (“Comp Plan” to friends). It enshrines goals as lofty as social equity and environmental sustainability. Its effects will be as specific as what sidewalk gets built where. It will shape what happens at the Pepsi site. (That project might be the first built out under the plan’s guidelines for very large development sites.) It will, in fact, inform what gets built everywhere.

We don’t want to say you should read the Comp Plan, because that’s cruel. But you probably should. You will live in the city it describes.

“We often hear something like, ‘growth is out of control, and we need a plan,’” says Eric Engstrom, principal planner at the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. “Well ....”

The Portland City Council approved the Comp Plan in June 2016, but appeals on some provisions were slated for March (after Portland Monthly’s press time). It’s scheduled to take effect in May.

The 2035 Plan will then join our nerd-canon of capital-P Plans. The state passed landmark land-use laws in the ’60s and ’70s, and some people still mist up at the mention of Gov. Tom McCall. Portland’s 1972 Downtown Plan laid foundations for Pioneer Courthouse Square and “people-movers” (ah, the ’70s) like the streetcar and MAX. The 2035 Plan replaces a comprehensive plan adopted in 1980, which presaged today’s booming neighborhoods and major streets—or “nodes and noodles.”

“Each time we do this, it takes years,” Engstrom says. “That’s why we only do it about once a generation.”

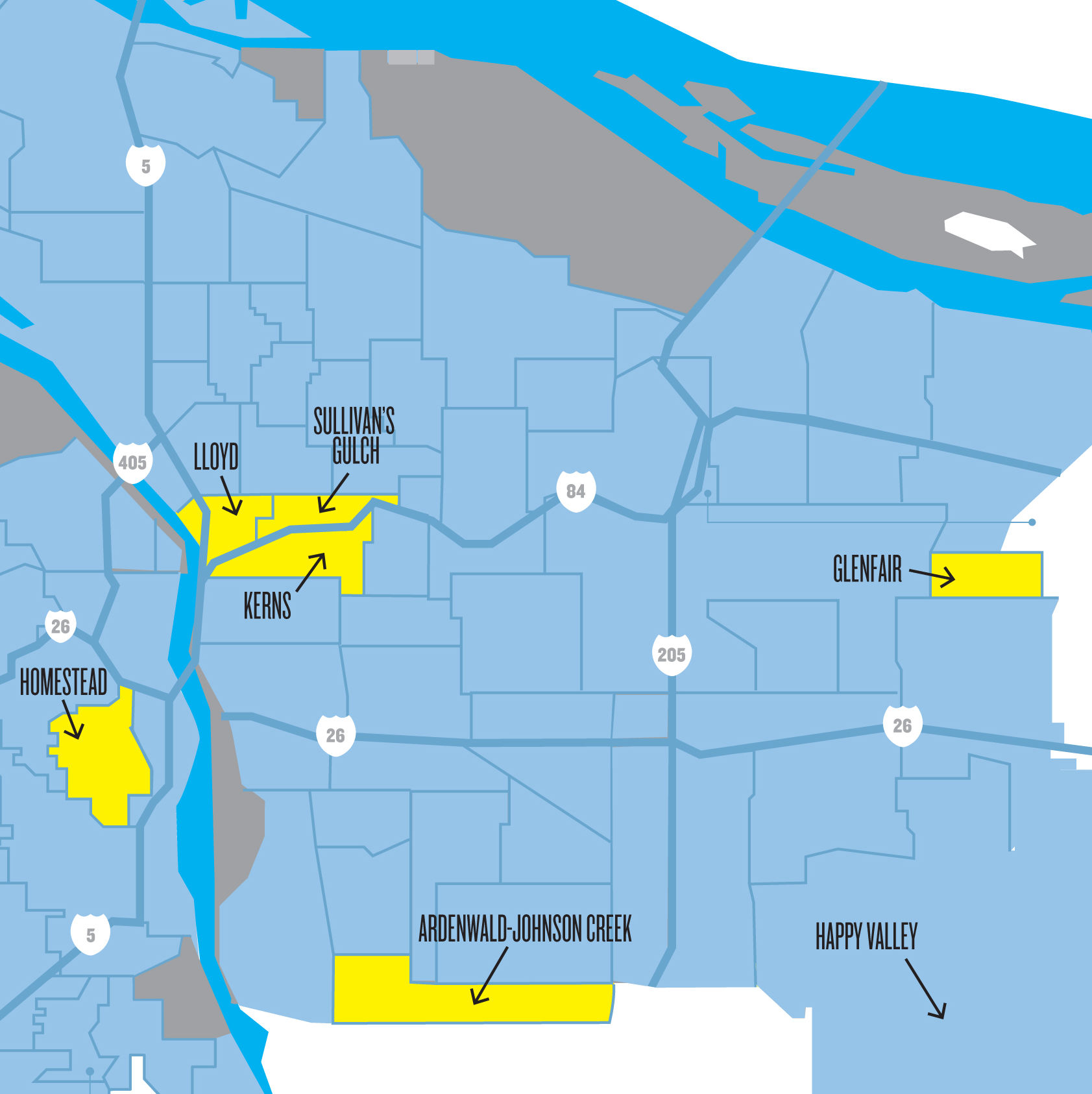

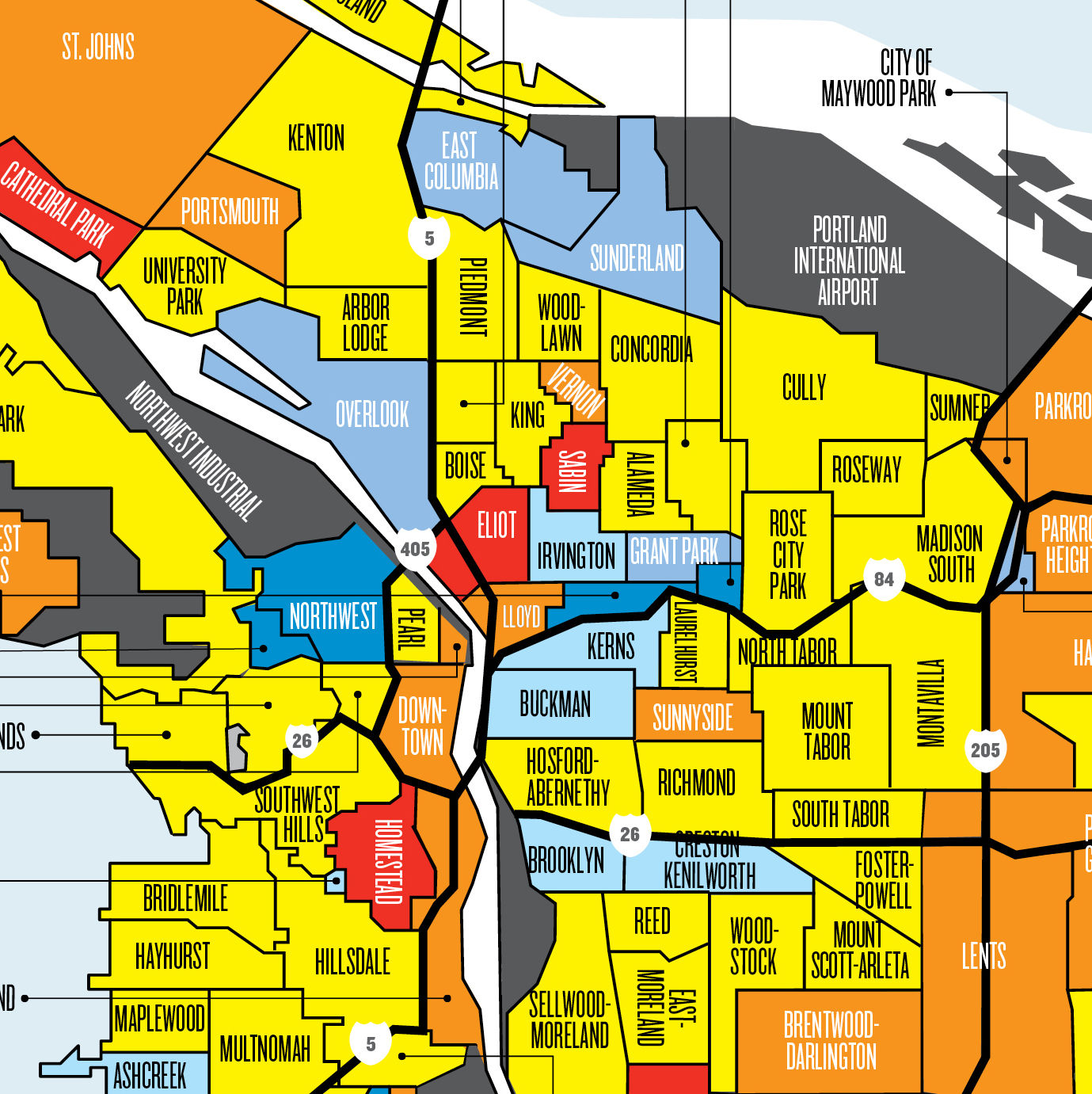

Think of the Comp Plan as Portland tinkering with its own DNA, changing zoning, plotting transit, rejiggering places as different as West Portland Park and SE 122nd and Division. In the crudest terms: where can big stuff go, and why, and where and how should humans live and move around?

“People live in physical space,” says Mark Raggett, a senior urban planner at BPS. “We’re trying to leverage growth into a place we want to be.”

There’s definitely an agenda, perhaps several. The plan aspires to a Portland where 70 percent of travel avoids solo car use. It doubles down on “nodes and noodles” to emphasize walkable “complete neighborhoods.” (There’s at least a conceptual acknowledgment that East Portland—mostly not even part of the city in the ’80s—differs from older, closer-in neighborhoods. “The zoning code of the old city,” Raggett says, “doesn’t really work for the new city.”) The plan envisions downtown absorbing 30 percent of population growth.

All of this comes together in a document that—however debatable—sets a dorky but real example of democracy in action. The city gathered about 30,000 pages of public comments; city council voted multiple times. If we’re worried about populism, the Comp Plan is something like the opposite: highly technical and process-brewed.

Wildlife habitat and migration corridors thread through our human streets and highways. Hospitals and universities, together, represent our fastest-growing job sector. Evolving demographics will shift local politics; discussion of a Southwest Portland light rail line likely to be built in the 2020s, for example, needs to involve the area’s growing Somali population.

“It’s not ’80s Portland or ’90s Portland anymore,” Engstrom says. “We’ll be more diverse, older, with more single people and couples without kids.”

At the Pepsi site, five acres are likely to become a miniature neighborhood: bigger and busier. “The larger view,” says Bert Gregory of Mithun, the Seattle-based design firm working on the project, “is that this fits in the context of Oregon figuring out how to accommodate all the people who are moving here.”