Can One of Portland’s Poorest Neighborhoods Build Its Way to Prosperity?

Image: Courtesy City of Gresham

Josh Fuhrer grew up in Rockwood, once a stagecoach stop named for its landscape, now a neighborhood on Gresham’s border with Portland. He studied theater in New York and returned to his hometown. Then, one afternoon before a performance, a car hit him at 35 mph. Fuhrer mended, but his neck turned too “creaky” to continue acting. So with his winning smile and smooth, clear diction intact, he turned to developing buildings.

“Theater and development are analogous,” Fuhrer says. “You want to tell a story. You hire designers for sets and costumes and a crew to build it all. The tenants are the actors. You open the doors, and the audience comes in.”

Fuhrer’s latest production—a 5.5-acre development known as “Rockwood Rising”—will soon take stage less than a mile from his childhood home. Three stylishly designed new buildings surrounding a colorful plaza will house a public market and cluster of training and business development organizations. More than 100 units of workforce housing will include 22 designated for people making 80 percent of the median income or less. As head of Gresham’s urban renewal agency, the former actor has scripted an ambitious effort to spark prosperity by combining commerce, education, housing, social services, sparkling public space, and a comeback tale for one of the metro area’s poorest places.

“By colocating these economic resources,” Fuhrer says, “folks will be able to see their individual household income rise as the community around them arises.”

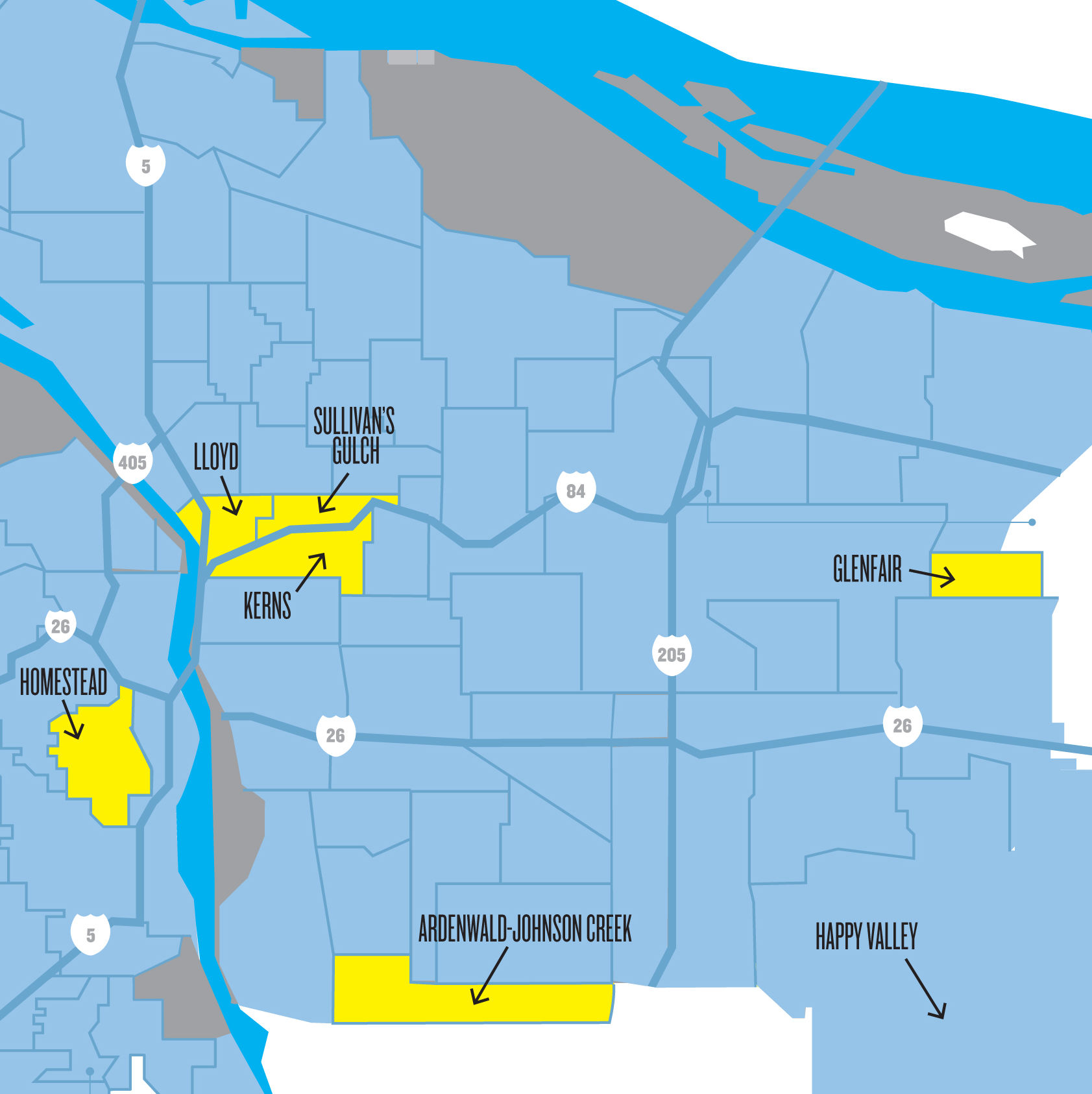

The site has long been a field of dreams. Brightly marked by a neck-craning, orange-and-violet public sculpture rising like the historic Ferris wheel that once spun there, the parcel sits off Burnside, next to the MAX’s 188th Avenue stop. A 1994 Metro plan envisioned a high-density “town center.” After a Fred Meyer closed in 2003, Gresham bought the property, scraped it, and made it the heart of that city’s first and only urban renewal area. Developers sniffed around, but failed to pick up the bone. (Homer Williams proposed a YMCA; real estate experts suggested gated townhouses.)

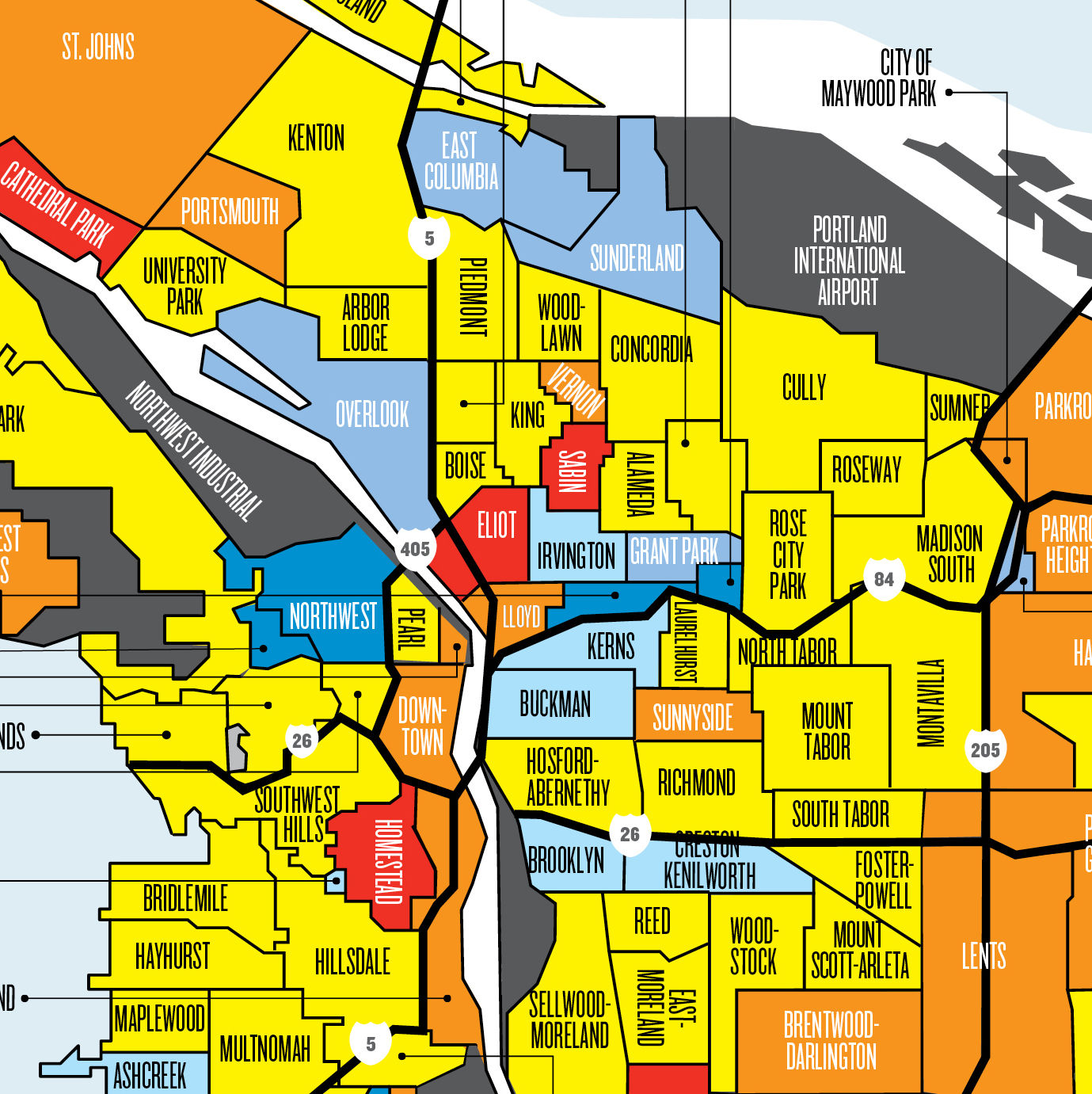

Thus the site and much land directly around it became a void at the heart of Rockwood, where cheap midrise apartments now house one of the region’s youngest, most diverse demographics (median age 32, about 80 languages spoken). In the past two decades, six of the area’s seven major grocery stores closed. Since 2011, the district’s median income has plummeted; in 2016, 34 percent of residents lived below the poverty line. Within the region’s affordability crisis, Rockwood remains one of metropolitan Portland’s last cheap places to live.

Fuhrer created some small Portland developments (among them, Woodlawn’s Classic Foods, an Italian food wholesaler that provides free spaghetti to schoolkids from low-income families, as well as community space). He dreamed of uplifting his old neighborhood. He landed on Gresham City Council, helped reshape its urban renewal strategy, then quit to lead the city’s redevelopment agency, where he hired four liaisons from Rockwood’s rainbow of ethnic enclaves to poll residents. Dozens of public meetings were translated into languages ranging from Spanish and Arabic to Tongan.

Over two years, Fuhrer’s agency shaped a tenant cluster with Swiss-watch intricacy: job-training organization WorkSource Oregon; Mt Hood Community College’s small business center; MESO, a microenterprise counselor and lender; and MetroEast Community Media, which teaches media and computer skills. An alternative program serving at-risk youth, Rosemary Anderson High School, is poised to locate its construction apprenticeship program there, along with culinary arts classes. A “market hall” will offer discounted space to budding food entrepreneurs and four grocers. In the still-standing former Fred Meyer barbershop, MetroEast is already at work, offering computer training in eight languages.

As a spring groundbreaking nears, however, Fuhrer’s ensemble production already has its critics. “Rockwood Rising has many good things,” says Cameron Coval, director of Pueblo Unido PDX, an immigrant rights group. “But without affordable housing, it will displace the very people it’s trying to help.” Last fall, Pueblo Unido began filling city council meetings and held an outdoor rally, “Save Rockwood!” The project, the activists argued, is “mired in conflicts of interest” and should pause until Gresham has a “coherent housing policy.”

Indeed, surrounding rents have already risen. And some of Fuhrer’s cast members mix roles. Brad Ketch of the Rockwood Community Development Corporation, who helped lead much of the public outreach, is also part of Sunrise Development, which is building 44 units of market-rate family housing next door. The Rising’s private partner, Roy Kim, has owned a parcel across the street for a decade. Both are adamant that these are separate from Rockwood Rising.

“We’re trying to do urban renewal differently than some cities,” Fuhrer adds, his eyes rolling toward the west. “Many great organizations offer poverty alleviation. There hasn’t been a focus on prosperity creation. Can we grow people into the middle class?”