Light A Fire 2011

Inspiring our Next Generation

Multnomah Education Service District Outdoor School

Da Vinci Arts Middle School sixth graders with their counselor, “Pawt Stikkr,” after a soil field study

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Hands up: who’s licked a slug? If you attended the sixth grade in Multnomah County, we’re betting you may have … or that you brought back some other camp stories from Outdoor School, a sleepaway environmental education program that’s become a legendary institution since its inception in 1966. Free to most participants and part of the annual sixth-grade curriculum throughout the county, Outdoor School and its annual team of more than 1,300 high school volunteer counselors ensure every student experiences and learns about the natural world at camps near Corbett and Sandy. Students make leaf rubbings, observe migratory birds, and examine invertebrates under a microscope. (And on a dare, some might even sample “Oregon escargot.”) There are other lessons too: away from home and outside of embedded social patterns, Outdoor School creates a safe space for personal growth. “Even the students who were troublemakers in the classroom opened up and had the time of their lives,” says Katie Kramer, who spent five springs as an Outdoor School counselor and special-needs volunteer. “They got a taste of being part of something bigger than themselves: a community.”

Arts & Culture

Northwest Film Center

A full house at the Northwest FIlm Center (front row, from left): Bill Foster, executive director; Jessica Lyness, public relations and marketing director; and Ellen Thomas, education director

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

In an era of Netflix and Hulu, it’s all too tempting to forgo the movie theater in favor of sweatpants and an easy chair. The Northwest Film Center offers a damn good reason to ignore that urge. An important regional resource for filmmakers, students, and visiting artists, the Northwest Film Center has been reminding us for 40 years that “film” embodies more than just the latest Hollywood blockbuster. Its hundreds of screenings each year include smaller films like “Pulp,” a short by an 11th grader questioning the violence in boxing, or The Klezmatics: On Holy Ground, a documentary about a Grammy-winning klezmer group that showed as part of the Jewish Film Festival. “Moving images are so central to the way our society operates,” says the center’s director, Bill Foster, “not just as entertainment, but as the documentation of social change and personal expression.” With classes like sound recording and screenwriting at its School of Film, the center inspires people of all ages to express themselves with movies. And each winter during the Portland International Film Festival, which drew a whopping 35,000 attendees in 2011, the Northwest Film Center spurs the rest of us to get out of the house and enjoy them.

Sustainable Planet

The Wetlands Conservancy

Wetlands Conservancy executive director Esther Lev at “Milwaukie’s best-kept secret,” Minthorn Springs Wetlands

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

The next time you sit down to a plate of cedar-plank Pacific salmon for dinner, be sure to raise a glass to the Wetlands Conservancy. Without the group’s effort to educate the public about the importance of wetlands in everything from preventing flooding to their essential role in providing healthy habitats for salmon, your plate might well be empty. Over the course of its 30-year history, the Wetlands Conservancy has helped raise awareness about these sensitive marshy areas with posters, TV spots, and even on-the-ground guerrilla efforts like the neighborhood gathering it organized in June to educate Tigard residents with yards adjacent to the Roger Hart Wetland Preserve about how to plant and care for their land with the wetland in mind (not using pesticides that will run off into the fragile ecosystem, for example). This spring, the group ran an Aqua Plate Special at local restaurants and grocery stores to raise awareness, identifying seafood that depends on healthy Oregon estuaries. The effort also netted $9,000 in donations. “We want people to understand how wetlands are more than just really cool spaces,” says the group’s executive director, Esther Lev. “They provide functions that intersect with people’s lives.” The Wetlands Conservancy isn’t just sis-boom-bahing wetland preservation, though; it’s an active player in acquiring land. Since the conservancy was founded three decades ago, it has procured more than 1,600 acres around the state, including a preserve in Yaquina Bay and 56 acres in Tualatin. “The Wetlands Conservancy plays a hugely important role in conservation in Oregon,” says Bob Sallinger, conservation director for the Audubon Society of Portland. “There are a lot of land trusts out there, but the Wetlands Conservancy stands out because they bring science and stewardship to the lands they protect.”

Best New Nonprofit

Creative Cares

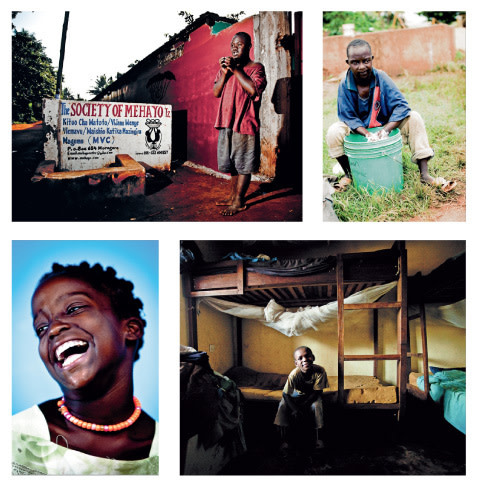

Photographer Burk Jackson’s Tanzania images

For nonprofits, creating a compelling story of accomplishments through video, photography, and the written word can mean the difference between luring future-redefining grants and gifts and laying off staff members. Enter CreativeCares, a fledgling nonprofit that pairs creative professionals with the charities that need their skills. Founder Burk Jackson, a veteran freelance photographer, calls the service a kind of Match.com for creatives willing to donate their time to the nonprofits that inspire them. Since its inception in 2010, CreativeCares’ roster of more than 80 copywriters, graphic designers, photographers, filmmakers, and more have helped tell the stories of nonprofits serving everything from Oregon’s homeless population to disabled children in rural Tanzania. In the coming year, Jackson aims to bump his well of creatives and nonprofits to 1,000 each. “Thirty years ago Mercy Corps was just an idea,” Jackson says. “As creatives, we need to be asking, ‘How do we support the other nonprofits to help them become that kind of organization?’”

Honoring our Elders

Senior Citizens Council of Clackamas County

In 2008, West Coast Bank received near daily phone calls from a 70-year-old woman complaining—not about check fees, but about her hunger. So the bank notified Adult Protective Services, which turned to the Senior Citizens Council of Clackamas County, a senior advocacy group. SCC’s investigation revealed that the woman’s family had moved into her tiny house and were squandering her Social Security checks, leaving her without money for food or insulin. The SCC quickly intervened: within two days, they had set the woman up with regular medical care and moved her out of the house. A few months later, they sold her house (depositing the money in her bank account) and ensured her Social Security checks stayed in her hands. Sadly, the initial scenario isn’t unique. Money is most often at the heart of the issues the SCC helps resolve, says executive director Christina Bird, one of just six staff members. In its 40-year history, the SCC’s staff and volunteer force of 25 have helped a small city’s worth of seniors—some 40,000—get back on their feet, be it simply helping them set up auto bill pay, moving into more affordable housing, or, sometimes, untangling more difficult familial financial messes. “Each referral is just as important to us as the one before,” says Bird. “Not only do we—in some cases—save lives, but we also preserve dignity.”

Keeping Us Healthy

Project Access Now

After Gordon Eastman lost his job in 2009, he began having a hard time speaking in coherent sentences. Without health insurance, and convinced he was losing his mind, Eastman ended up at a free urgent care clinic that attributed his impaired mental functions to a case of untreated diabetes. Since the clinic wasn’t set up for the ongoing treatments he needed, providers there turned to Project Access Now, a four-year-old group that helps connect uninsured low-income patients in northwest Oregon and southwest Washington with a network of 3,000 health care providers willing to donate their time. PAN determines what practitioner is the best fit for the patient’s needs, then helps schedule appointments at the physician’s regular offices and even provides appointment reminders and transportation. “A little bit from a lot of people makes a big difference,” says executive director Linda Nilsen-Solares. We’ll say. To date, PAN has connected nearly 6,000 patients like Eastman (who not only found his way back to health, but also found a new job) to the care that, in some cases, saves their lives.

Most with the Least

Farmers Ending Hunger

Farmers Ending Hunger’s staff of one: executive director John Burt

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

To say Oregon has a robust agricultural industry is kind of like saying New York has a decent fashion scene. In 2009 alone our state grew more than 50 million tons of fruit, and that’s to say nothing of the vegetables, grains, fish, and ranch products we also raise each year. Sadly, that bounty doesn’t always find its way to the mouths of our citizens; a new report from Feeding America ranks Oregon second only to Washington, DC, for childhood hunger. But Oregon growers of all kinds are working to change that through Farmers Ending Hunger. Launched in 2006 with a donation of 173,000 pounds of frozen peas, the program stocks pantries like the Oregon Food Bank, soup kitchens, and shelters with supplies donated by farmers and ranchers. Last year, the program distributed about 2 million pounds of fresh fruit and veggies, frozen produce, locally milled pancake mix, and ground beef. Yet after five years in operation, Farmers Ending Hunger still has just one employee—executive director John Burt—and operates on a shoestring budget. In essence, this nonprofit is powered by the people who till the land. “It’s been amazing to see how farmers step up,” Burt says. “They want to be good corporate citizens in the world, but also make the highly personal decision to feed hungry people.” We call that farm-to-heart.

Extraordinary Pro Bono Contribution

Wieden & Kennedy

Image: Wieden & Kennedy

When the creative forces responsible for Levi’s “Go Forth” campaign and the Old Spice viral video hits featuring Isaiah Mustafa turned their collective brain power toward the nonprofit world last spring, the results were, not surprisingly, pretty spectacular—$1.4 million in donations in a single night kind of spectacular. Led by account director Eric Gabrielson and creative directors Danielle Flagg and Tyler Whisnand (who typically work on Nike and Target accounts, among others), the Wieden & Kennedy team turned a dull Harvard Business School of Oregon report about the sevenfold return on investment for Friends of the Children into a clever, animated video about “Friendonomics.” The video was a cornerstone of the annual fundraising event for Friends of the Children, a local group that pairs professional mentors with vulnerable Oregon kids from kindergarten through high school, and is just one of the many projects to which Wieden & Kennedy has given its talent, gratis, over the past decade. “They treat us like a client and give us just as much respect as they would Coca-Cola or Chrysler,” says Megan Lewis, director of development and marketing at Friends of the Children. “When they have a creative idea, they execute it without any limitations.” For the Friendonomics project, the W&K team donated hundreds of hours—most of them after hours and on weekends—and relied on its stable of talented producers and stylists such as animator David Potter, whose credits include the documentary Deep Green and several projects for Coke, Nike, and Dodge. “That’s the spirit of this place,” says Dan Wieden, cofounder and CEO. “You give back whenever you have the opportunity. We feel like citizens who have a responsibility to create good, meaningful communication. It’s a real honor to do work with organizations like this one.”

Purely for the Love

Mission: Citizen

They may not have been old enough to vote, but that didn’t stop six Lincoln High School students from helping others earn their right to pick our political leaders. Inspired by their rigorous study of the US Constitution for a national civics competition, the students formed Mission: Citizen in 2009 to help immigrants pass their naturalization tests and become American citizens. Since then, dozens of Lincoln students have taught free eight-week courses to about 60 immigrants. Some, like Chan Chanthakoun, an immigrant from Laos, passed on the first try. Others, like Beatrice, a recent class attendee from Rwanda, proved teachers themselves. Beatrice struggled with the concept of political free speech, which Mission: Citizen cofounder Louis Wheatley says taught the Lincoln students not to take the rights afforded to Americans for granted. This summer Mission: Citizen garnered grant money from Community 101/PGE Foundation to expand the program and help even more immigrants … and students. “Their stories help push us to help them achieve a better life,” says Wheatley, now a sophomore majoring in history and romance languages at Dartmouth. “We’re thrilled and honored to be part of that journey.”

Extraordinary Board Member

Linda Wright

In 1990, Linda Wright heard about a little-known nonprofit dedicated to the simple proposition that at-risk, urban youth needed helping hands beyond their families and schools. To move beyond summer and after-school programs to 24-7 counseling and support, the organization, Self-Enhancement Inc, needed its own building—and millions to buy it. It took more than six months, but Wright, then vice president of community relations for US Bank, convinced the bank’s board to fill the gap by making what, to date, had been the largest corporate donation in Oregon history: $1 million. Today students who go through SEI programs graduate high school at a rate of nearly 100 percent (by comparison, the average four-year graduation rate in a PPS high school is 55 percent), and 85 percent of SEI students go on to higher education. Such success couldn’t have been possible without Wright’s 20 years of fundraising efforts. She has cajoled corporations; helped with Art+Soul, SEI’s highest-earning annual fundraiser; and last year even served as the group’s interim development director for six months. She calls herself an adviser, supporter, encourager, and confidante to president, founder, and CEO Tony Hopson Sr. “SEI would not be SEI were it not for Linda Wright,” says Hopson. “For every graduate of our program, and every success we have at SEI, Linda’s handprint is there.”

Extraordinary Volunteer

Barbara Rodriguez

Like so many dedicated volunteers, the soft-voiced Barbara Rodriguez would rather talk about the organization she supports than herself. But staff members at Adelante Mujeres (translation: rise up and move forward, women) have no problem gushing about the dependable woman who’s worked as a volunteer since the organization’s inception in 2002. Adelante provides continuing education and professional development help to 350 low-income Latina women and their families. Among other things, the group provides free business and GED courses, free training in organic farming techniques and marketing (including hands-on experience at the Forest Grove Farmers Market, which Adelante founded), and after-school programming for the children of working families. An indefatigable volunteer, Rodriguez donates the equivalent of five workweeks of her free time each year, serving on the board, helping Spanish-speaking preschool children prepare for kindergarten, and introducing the staff to new technologies. “Bobbie’s eternal patience, positive attitude, and resolute dedication to education and our organization are what make her an invaluable asset to this organization,” says Kate Jackson, development director for the Forest Grove nonprofit. A longtime kindergarten teacher in Oregon’s public schools and a former Peace Corps volunteer in El Salvador, Rodriguez says it’s the children who keep her engaged year after year. “I am never depleted,” she says. “Every day is a learning experience. As much as you want to teach the kids, they’re the ones teaching you.”

Extraordinary Staff Member

Beth Putz

After 13 years of working with kids in crisis at Albertina Kerr, an organization that serves children, adults, and families with mental health challenges and developmental disabilities, Beth Putz remains a diehard optimist. “You can’t last in this field if you flip to pessimism,” she says. When Putz started at Albertina Kerr, as a direct care worker in an inpatient program for kids, she did everything from cook breakfast to take the kids on bike rides. After receiving a master’s degree in counseling psychology, she eventually became the director of Kerr’s Crisis Psychiatric and Foster Care programs, where she’s now on-call 24/7 and regularly logs 50+ hour weeks, sometimes sleeping in her office (as she did during a 2009 snowstorm). And that’s just the time she spends inside Albertina Kerr. Putz also recently completed a 16-month long program through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to cultivate future leaders in community health care services. Her biggest push? Helping to identify the underlying causes of kids’ bad behavior to find long-term solutions. “These kids don’t have the words to express how they feel,” Putz says. “It’s our job to help figure out why they got here.” Her compassion also serves as an inspiration to her coworkers. “Beth has been instrumental in helping me be a positive supervisor,” says Anne Main, who works in Albertina Kerr’s Crisis Psychiatric Care division. “It’s easy to get frustrated with a child who cannot follow expectations, but as Beth likes to say, there isn’t a child who wakes up and says, ‘I’m going to have a bad day and kick or bite someone.’ They all wake up wanting to have a good day. That’s a quote I think about all the time.”

Extraordinary Executive Director

Keith Thomajan

When Keith Thomajan talks about things like “brand dilution” and “fiscal management,” he sounds more like the CEO of a Fortune 500 company than of a nonprofit. And based on his track record at Camp Fire Columbia, an affiliate of a 101-year-old national organization that operates coed outdoor camps, after-school programs for kids, and service-based road trips for teens, he could have easily spent his career garnering profits for corporate shareholders. When he took over as Camp Fire Columbia’s president and CEO in 2001, the organization had faced a decade of six-digit deficits. Thomajan promptly reshaped Camp Fire’s disjointed menu of programs (everything from preventing gang involvement to summer camps for developmentally disabled youth) to focus on high-quality after-school programs designed to help close the achievement gap for low-income youth. His vision quickly garnered a three-year grant from the Gates Foundation, which led to similar grants from other funders. He also instituted new fees for service—allowing more affluent members to subsidize programs for lower-income families—that have put Camp Fire Columbia in the black since 2004. Thomajan’s head might be in numbers, but his heart has always been with people. Soon after college, he taught high school in South Central LA and East Oakland before becoming an Outward Bound instructor. While kids have shaped his sense of purpose, his coworkers keep him excited about his job. “People who are dreamers and want to make a difference, and have a profound toolbox to do so, make me love coming in to work,” he says. “I get amped by their energy.”

Lifetime Achievement

Linda Huddle

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Linda Huddle’s retirement last year from her post as director of Portland Community College’s Alternative Programs marked the end of a 40-year-career as one of Portland’s most effective advocates for at-risk youth. “These are kids who want the best for themselves and their families but don’t have the right doors available to them,” she says. “Our role as teachers is to open those doors and help them step through and succeed.” Huddle began her extraordinary career as a Spanish teacher at West Linn High in the ’60s. She spent nine years as the youth program manager for the Private Industry Council, which afforded job-training programs to some of Portland’s hardest-to-reach youth. She joined the board for Open Meadow, a nontraditional school in North Portland for struggling students, and was a founding board member of the Youth Employment Institute, which offers everything from gang prevention services to GED classes. In 2000, she became the director of PCC Prep Alternative Programs, allowing her to improve programs to steer troubled students toward completing high school and into college or employment. In that capacity, she codeveloped the Gateway to College program, which helps high school dropouts fulfill collegiate dreams by letting them achieve a high school diploma while earning college credit. The program has expanded into 16 states—and, last year alone, to 100 school districts—thanks in part to an initial $4.8 million grant from the Gates Foundation. “Coming to PCC allowed Linda to bring her previous experiences together to create something really big,” says Pamela Blumenthal, interim director of PCC Prep Alternative Programs. “She’s an absolute visionary.”