Carrie Brownstein: The New Icon of Oregon Feminism

Image: Andy Batt

If you’re looking for the face of Oregon women circa right now, go no further than Carrie Brownstein: effortlessly cool, fluidly intelligent, dauntingly accomplished, but firmly grounded and quintessentially of this place. In the last year, she reunited with legendary band Sleater-Kinney and recorded an album already hailed by critics. She cowrote and filmed the fifth season of Portlandia, her sketch comedy show, and released a spin-off cookbook. She finished a memoir, took on a rewrite of Nora Ephron’s last screenplay, and played a small but key role in the Amazon series Transparent. So, yes—in addition to being a refreshing icon of feminism, she’s also a little busy.

What defined 2014 for you?

2014 was a year of tackling new projects and finishing certain endeavors that were hanging over my head. I finished writing a memoir, I was hired to do a rewrite on the last screenplay that Nora Ephron had been working on, and I started working on the show Transparent, all of which were new and exciting and frightening projects for me. And also exhilarating. I think of it as a year of risk-taking and transformation.

What about Transparent appealed to you?

The appeal was getting to work with Jill Soloway, who I think is one of the smartest, most innovative, funny, creative, unabashedly feminist women that I know. She’s just a risk-taker, and I think she’s just wonderful and inspiring. I had been a fan of hers for a long time and just jumped at the opportunity to get to work with her. It was a version of a family that I definitely could relate to—and I think anybody could relate to. I always desire to be part of art and creativity that people feel a strong connection to, that can change people’s lives, that can make a statement. I think Transparent functions on a multitude of levels: one is just a great dark comedy about a family, but it’s also a new frontier of television and I’m really excited to be a part of it.

What does the future look like for Sleater-Kinney?

There are some things that are so familiar about Sleater-Kinney—so intrinsic. It’s hard to kind of separate the formative years of my life from Sleater-Kinney—they’re kind of one and the same. It was my love relationship: a substitution for my education, my romantic partnerships, my travel—it encompassed so many permutations of what it means to be growing as a human and learning. It was really experiential, but informed so much of my world view and how I sort of came to see who I was in the world. My identity was very much wrapped into it. But at that same time, it was something that I let go of. That was my 20s, and then my 30s have really been defined by Portlandia.

It’s complicated, because sometimes with a band especially, because of the way that people relate to and listen to music, can feel like a force outside of yourself, where you’re just one facet of what it is. Sometimes it feels like it’s its own entity that I’m just catching a ride on…like it’s some kind of satellite that’s coming around and I’ve decided to hitch my ride to it again. Because it does really have its own momentum and life force. So I feel a lot of happiness about reconnecting with Corin and Janet and the music, and I think our intention was very much based in the here and now, which is why we decided to make a record instead of just going back out on tour. But I’m wary of nostalgia as a motivating creative force—I think it’s good to have a dialogue with the past, but it’s more dynamic to have a dialogue with my present self. I’m just curious and looking forward to what this version of Sleater-Kinney is. But I’m glad we’re able to approach it through new material, so that it doesn’t just feel purely based on sentimental urges.

How will No Cities to Love sound to Sleater-Kinney fans?

Hopefully the record will sound new to them, like something that was put down in 2015 and has the urgency and the freshness and the relevance of any record we put out. I think that it is a personal record, and it has a desperation to it—because there really is no “settled” version of Sleater-Kinney. So hopefully people hear that restlessness, but that the shape of that agitation is in really catchy choruses and hooks. I think it’s an accessible record, and I hope that people feel understood by it. That’s what I love about music—listening to something and feeling seen and feeling understood, and feeling a sense of elation. Just recognized. For me, with some of my favorite bands and songs, I see myself in those songs, and then you just feel more alive. So I guess I hope the same for anything I put out into the world.

As a Portlander yourself, what do you think it is about Portlandia that hits home?

I think part of it is the earnestness about it and the kind-heartedness that is at the root of the intention behind it. I think with comedy, when you’re too prescriptive or too negative (which I think is totally fine—I think there are brands of comedy that are just acerbic and incisive, but that can be mean), it can keep people at a distance. A lot of that well-meaning spirit to Portlandia allows for a sense of discovery, and allows the audience to take a step into the world of the show, which I think they have done in spades. One is seeing themselves or people they know in the characters.

Obviously Portland, in the world of Portlandia, is a substitution for any number of cities or lifestyles or just a mindset that permeates so much of the US and internationally. I think that there is a creeping awareness, as you look around at some of the constant turmoil in the US and abroad, that when we concern ourselves over these minutiae, that there is a privilege that goes along with that. And so I think people know that there’s a privilege that goes along with having your favorite places to eat and favorite coffee shops be your biggest worries. I think that’s just part of a bigger dialogue now about where we are and who we are, and I think Portlandia has kind of tapped into that cultural conversation about living in these highly curated spaces, but at the same time I think what keeps people coming back to the show is the characters. Each duo is a very loving friendship between Fred and I, and each character is infused with a genuine affection for other people and for place. I think people think a lot about their relationship to place. They’re either in concert with it or in conflict with it. I think that’s just what people relate to. But I’m continually surprised and delighted when people dress up as our characters for Halloween and stuff. I think what people in Portland might find surprising is that cops in New York come up to Fred and I and say that they love the show, or that people 60 miles outside of Salt Lake City in rural Utah like the show. It has an appeal that I feel very proud of, especially coming from indie rock, which sometimes feels like a very narrow spot of fandom. I like how television can just be a little more populist. That feels good to me.

Which is your favorite Portlandia character to play?

I love playing Toni, who is one half of the feminist bookstore. First of all, she just gets to wear really comfortable clothes, which I think is amazing. But it’s like when you’re wearing comfortable clothes but you’ve accidentally kept the tag in it. So there’s something just kind of always rubbing you the wrong way. She’s just always slightly on the verge of irritation. I like to be able to get into that contrast of comfort but then feeling like I’ve got a rock in my shoe. I think that’s such a relatable state of being: you’re really trying to embrace this equanimity, but then there’s still that pebble in my shoe! To me that’s almost a philosophy people live by: everyone’s embracing positivity but then you’re just like, “Dammit, I can’t be positive about everything. Things are just shitty. Things are terrible!”

How did you find the experience of writing a memoir?

Well, writing a memoir was definitely the most isolating of all my projects. I’m used to working in creative partnerships, and I really thrive in that environment. It really just boiled down to changing my methodology and discipline. It’s an unavoidable task. You just have to write. There is no version of writing that can happen without you actually writing. It sounds so basic, but there’s just no aimless, half-assed version of it. There are so many other things in life that you can multitask with, or half-heartedly engage in, but there’s just a focus and an inevitability with this. At some point, you are just typing. That inevitability, and coming to terms with the process—like, put your fingers up against the keys and form the words!—it’s just the simplest task with such high stakes. It’s just a mountain and you see it and it’s like, “I guess I will get to the other side, I don’t know how. Well, one step at a time I guess.” The most logical answer is the only one.

Video by Andy Batt

So, are you happy to be on the other side of the mountain?

Yes, I never want to climb it again! Or not for many years. There was such a sense of exhilaration when I printed out the manuscript for the first time. Because it exists in this ether on your computer, and it’s mediated by the same screen that you look at Twitter on. I remember I printed it out to just do some edits and have a different set of eyes on it and make it more tactile, and I just couldn’t believe it. I was like, “Oh my god, there’s over 200 pages here!” I just felt like I’d won an award, like, “I don’t care if anyone ever reads this, but I did it.”

Who have been your biggest role models as you’ve pulled the pieces of your career together?

I definitely look at people who I think have continued to work through different iterations of their lives and careers, and I think the keyword is “relevance.” Relevance transcends age, it transcends medium—as long as people out there get what you’re doing and want to be a part of it. I think of somebody like David Byrne, who is always pushing himself and collaborating. There’s just a certain humility that goes along with trying new things. Because you are very aware that you might fail. Like if you partner up with somebody different and dip your toe into some new field or some new discipline, that it may not be as successful. But the payoff is that you raise the stakes for yourself again. Which I think as a creative person is really important, to not get into a sense of feeling entitled or smug.

I think David Byrne is my favorite example of that, just because at the core of it, there is a curiosity. And the thing about curiosity is that it keeps you as a fan. And I think that for me the most common through-line in everything I’ve done is that I’m a fan—of music, of television, of film, of writing. And I think to be a fan is to be open, to be curious, and to be a seeker. And so I think the people that maintain that sense of fandom are the ones to emulate.

Who inspires you in your own life?

Miranda July is one of my oldest, dearest friends. I just love the way she thinks—it’s so inventive. I just think the way that she subverts everything from language to narrative to genre—that striving to look at something from an outside perspective and bend the audience toward the periphery instead of vice versa—is really wonderful. She’s always just been a huge inspiration to me; she’s very encouraging, she’s very kind, she’s very inspiring. And we have been in dialogue since we were 19 about our lives and our work, and I think I just wouldn’t be who I am without her and without that friendship and that ability to kind of lob stories and ideas and check in with each other.

When did you realize that you wanted to be a performer?

I’ve always been a performer, ever since I was a kid. It was my way of relating to my family, relating to a room of people—to draw attention to myself. I was an anxious child, and there was a lot of anxiety in my home. It was a way of harnessing that chaos and turning it into something that felt intentional instead of something that felt scary. So I think I just learned it as a coping mechanism to kind of retreat into a fantasy world where everything was kind of elevated and performative. So I really have done that ever since I remember: putting on radio plays, gathering my neighborhood friends together to do talent shows.

What is your biggest challenge in life right now?

I think the life/work balance is something that is always something to reexamine. Finding ways of doing all the things I want to do and being ambitious and striving—but also being a good friend and a good family member and a good partner and finding ways to cohere all of those things. There’s your own internal critic, and then there’s this white noise of criticism you hear if you’re an ambitious woman: to figure out ways of balancing, or doing it all. But what is doing it all? I just want to be happy. And I think it’s OK for work to make you happy, because it’s not just as simple as “work.” It also means collaboration, it means friendship, it means community. I think it’s really easy to ascribe something negative to women who love their work and love to dedicate themselves to that. But work is not a vacuum. Work is a culture and an environment, and it’s about communication and respect and kindness and friendship. But at the same time, I am trying to find a balance. If I can take a five-day vacation in 2015, I’d be really happy.

How does Portland play into that balance?

I think of Portland as the place I reset. The landscape here has so much to do with my sense of well-being and returning to a place that’s familiar, and it’s really informed almost everything I’ve ever done. To me, it has very little to do with the food or the coffee or some of the more new-fangled characteristics of the city. To me, it has to do with how verdant it is, how the air smells after it rains, or the way that clouds clear away for just 30 minutes and there’s a spotlight of sun on a corner that you walk through. It’s just these very particular moments of beauty and wonder that you can stumble upon in Oregon and in Portland, and I love that. I really require those moments for making me feel like myself.

What do you love about being a woman in Oregon?

I guess I don’t know what it means to be anything else in Oregon—I just don’t know any other way of being. I do think that there really is a pioneering spirit to the Northwest. You have the whole country in your rearview mirror, and there’s a lot of things worth learning from, and a lot of things worth leaving behind in terms of outdated, outmoded ways of thinking. So it’s kind of nice to be at the edge over here, and feel like we’re leading the way.

If you were the editor of Portland Monthly and pulling together an Oregon Woman issue, who would you put on the cover?

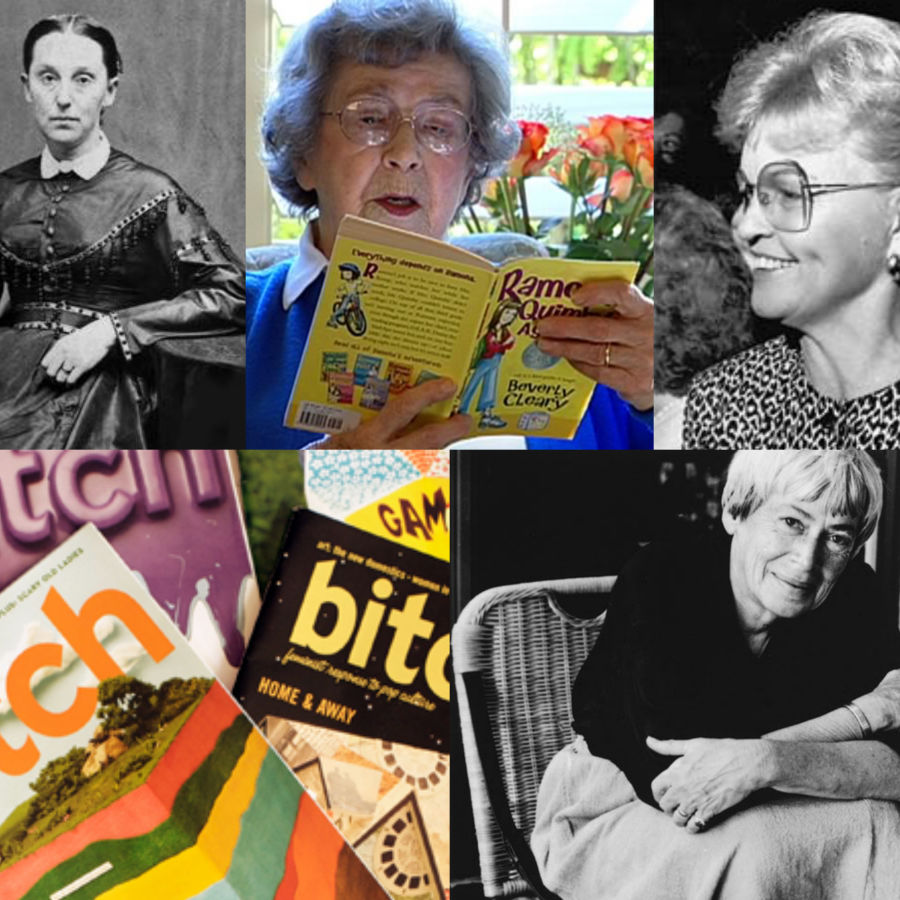

I mean, really, if you were Portland Monthly, which you are, the most fair thing to do would have just been to put a composite of 10 different kinds of Oregon women on the cover. That’s the most Portlandy thing you could’ve done—just put many women on the cover. Literally, every woman in the state on the cover and then you’d receive zero complaints. Or you could’ve just drawn a yellow smiley face with breasts, just something super generic, and affixed it with boobs. But then someone would be like, “Those aren’t my breasts. Those don’t represent my cup size.”

Anything you wish I’d asked you today?

I don’t know, I think you asked me all the right questions. Especially because you didn’t ask me what my favorite restaurant was, or what park I love, or what my favorite route in Portland is. But I will tell you that my favorite street to drive in Portland, a good cut-through in Northeast, is NE 47th Avenue. Check it out, everyone.