Writer and Private Investigator Rene Denfeld on Portland Sexism

"My biggest challenge has been to advocate for my kids, adopted from foster care. This is not a good city for poor people, minority children, or people with learning challenges."

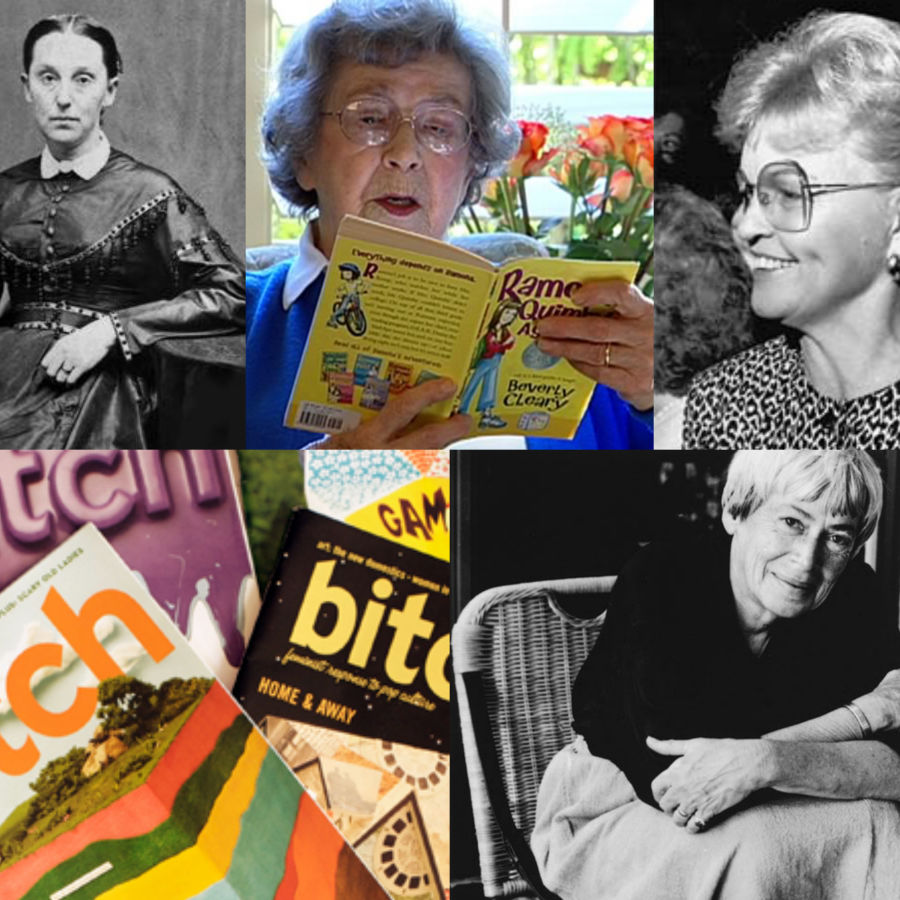

Image: Nicolle Clemetson

Twenty years ago, you wrote The New Victorians, a book criticizing the feminist movement for losing touch with ordinary women. Is that still true?

A lot of stuff in that book, if you wrote it now, people would say, well, duh. At the time, feminism was reeling from extremists like Andrea Dworkin and Catherine McKinnon. There was a real feeling that dissent within the movement would be quashed. Today, a whole generation of women demonstrates that feminism can embrace diversity of thought and debate. People can say, I can be a feminist and support free speech. I can even look at pornography and erotica. So things have improved a lot in those regards. Whether things have improved as far as actual equality is concerned is another matter.

How has being a woman in Portland changed?

There’s such a focus on this cutesy, utopian vision of Portland. That’s just not reality for most women here. Many of the changes in the city that are presented as good are, in fact, really terrible for poor women. Look at all the attention that’s paid to restaurants. Behind all the glowing restaurant articles, a whole bunch of people, usually minorities, are in the kitchen washing dishes. We’re creating a caste-based economy where poor people are underpaid to serve rich people. It falls hardest on poor women—often single moms who are trying to raise kids.

The current popular image of Portland definitely doesn’t include a lot of working-class people.

A friend of mine, Sarah, recently died. She was 25, mom of three young kids—a poor, working person in outer east Portland. She developed a bad toothache and couldn’t afford to go to the dentist. The autopsy found that the infection had spread to her bloodstream and killed her. That’s just an example of what life can be like for women in this town. There are countless women living in substandard housing—cheap, rat-infested apartments, trailer courts where conditions would shock people. It’s not all riding your bike with your hair in pigtails. It’s not the Portlandia episode.

You recently wrote a New York Times essay about growing up, for a time, in a household led by an abusive pimp. How does your upbringing influence your outlook on Portland?

These things formed me: growing up very poor, a white person in a predominantly African-American family—my siblings are African-American—and attending so-called “inner city” schools. I was the only white kid in my grade at Woodlawn. And I consider it a blessing, seeing what life is like from a different angle. I was out on my own at a young age, and I’m self-educated. Most people in this country don’t go to college. Most people in Portland aren’t graduate students. My background is a lot closer to that of the majority of people than to the educated minority.

It’s very strange, given my perspective, to see how Portland is presented. Flouride—classic example. People’s concerns are about…organic food, or these sorts of things. When you grew up around people who can’t afford to get their cavities filled, it’s strange. The things that people get embroiled in here can be completely foreign to me.

Your recent novel, The Enchanted, is based on your real-life work as a private investigator specializing in death-penalty cases. You’ve worked for public-defense attorneys, and written a nonfiction book about violent street kids. How does being a woman affect your ability to do that kind of on-the-ground work?

I think it allows me to do the work. I can go into situations without assuming poor people are scary or bad. When I worked for the public defender’s office, I did a lot of prostitution cases. I’ve lost count of the number of sex trafficking victims I’ve worked with in Portland. Women are beaten and abused and kept in awful little apartments. Behind that whole weird Portland thing of, oh, we like to go to strip clubs because it’s cool, a lot of strip bars—not all, but a lot—are fronts for trafficking women.

Very few men can do death penalty investigation. There are only a handful of us, anyway, but most of us are women in our 40s. We have some life experience, and we can be compassionate, and empathetic, but it’s also pretty hard to fool us. We’re 100-pound bullshit detectors. People will tell me things they wouldn’t tell a man.

Is Portland sexist?

We have a lot of wonderful, strong women here. In a lot of ways, it’s a great city to be a woman—a white woman. But the political infrastructure has been very male dominated. We have a discomfort with open, vigorous debate. One effect of that has been that women who are vocal and assertive tend to get labeled as troublemakers. Name Portland’s Bella Abzug. There isn’t one.

Culturally, this city is bizarrely in love—especially the media—with this neo-traditionalism: women, in the kitchen, baking their own bread and raising chickens. Those things are not bad, but it’s an image you could pluck out of Little House on the Prairie. The women are going to raise the kids and the chickens, and the guys are going to grow beards, drink beer, look like lumberjacks and throw darts. It’s fascinating.

What should we be focusing on?

Rising housing prices are a huge concern. There’s such a focus on creating housing for young professionals, but what about a woman with children? It’s almost like you don’t exist. We’re concerned with the “creative class”—as if other classes can’t be creative—but ironically the conditions that allowed artists to thrive here have begun to disappear. What kind of Portland are we creating for women of the future, or for women who want to have children, or for women who don’t come from backgrounds of privilege? We need to think about what we’re creating for everybody.