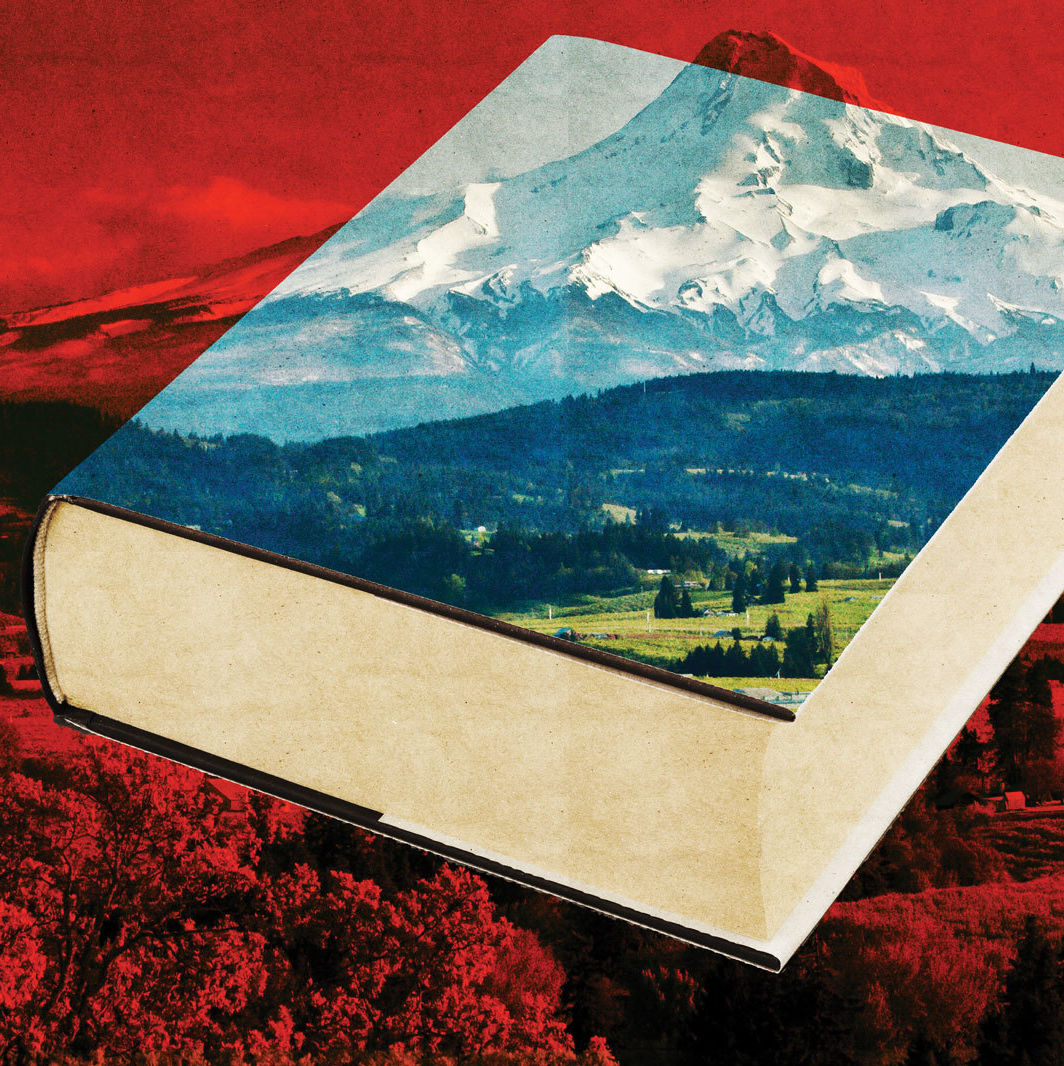

You Think Portland Traffic Is Bad Now?

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

You’re not imagining it. The traffic is real. Just in the last year, the number of vehicles on Portland’s roads increased 6.3 percent, according to state stats. The situation will probably get worse.

The Portland Bureau of Transportation—echoing many other predictions of explosive growth—estimates that by 2035 the city will add 260,000 residents, commuting to 140,000 new jobs. If current habits continue, that means about half a million more daily solo trips. And as the opening of the MAX Orange Line in the midst of last year’s traffic surge demonstrates, shiny new mass transit can’t relieve the congestion on its own.

More roads, you say? There will be no more roads. At least, not any new major highways. Leave aside social and environmental concerns: there just won’t be money. Funding for major infrastructure improvements raised through Oregon’s 30-cents-per-gallon gas tax is dwindling due to fuel-efficient cars and inflation. Meanwhile, the feds, who wasted a decade on short-term transportation stopgaps, just passed a $325 billion transportation bill that no one knows how to pay for. The grand visions of a Public Works Administration just ain’t coming back.

But there is good news. Strategic tweaks to existing roads can have far-reaching effects. This spring, Portland officials will finish an overhaul of the city’s 14-year-old Transportation System Plan (TSP)—a comprehensive blueprint for our road strategy for the next two decades that encompasses 331 city projects tallying $1.6 billion. The last TSP, planners say, was more like a giant wish list of big projects. The new plan pinpoints major population centers and traffic corridors that will absorb our growth and lays out realistic fixes.

The state is also trying to do more with less. “Most of our system is pretty old,” says Don Hamilton of the Oregon Department of Transportation. “The most important thing we can do is maintenance.”

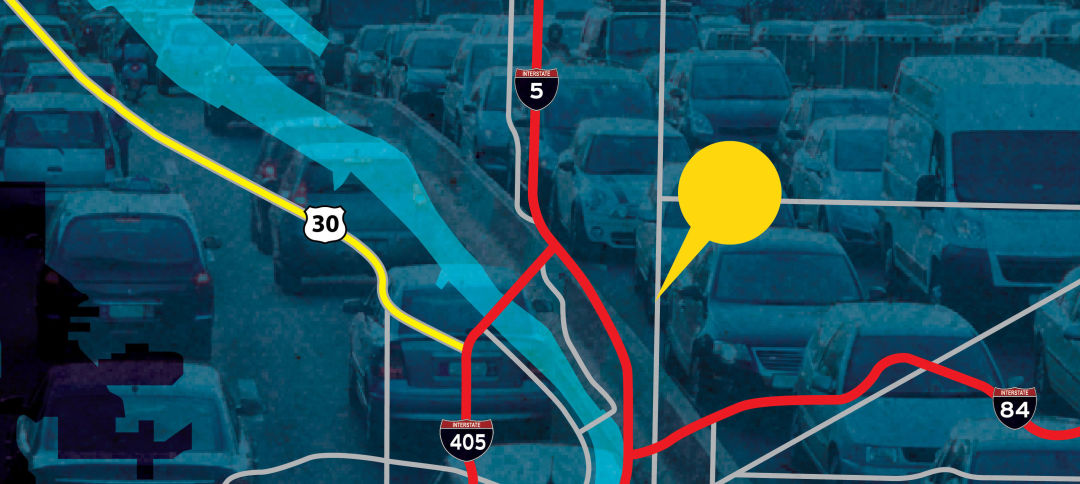

I-5 NORTH TO VANCOUVER, WA

Pressure point: Near constant daily congestion after 3 p.m., as 60,000 Clark County residents commute home from Portland. “The northbound span [of the bridge] will celebrate its 100 birthday in 2017,” says ODOT’s Hamilton. “It’s got narrow lanes and virtually no shoulder. So any little problem on that bridge will cause big backups.”

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: After the ignominious 2013 collapse of plans for the controversial Columbia River Crossing… nothing. For the moment.

NE COLUMBIA CORRIDOR

Pressure point: A busy, industrial thoroughfare

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: The area will be a testing site for PBOT’s ambitious new mobile app plan (currently seeking federal funding), which the agency hopes will allow users to compare car-sharing, biking, walking, driving, and transit options in a single glance. “LA just launched a mobile app that even compares calories burned and carbon footprint per trip,” says PBOT’s Art Pearce.

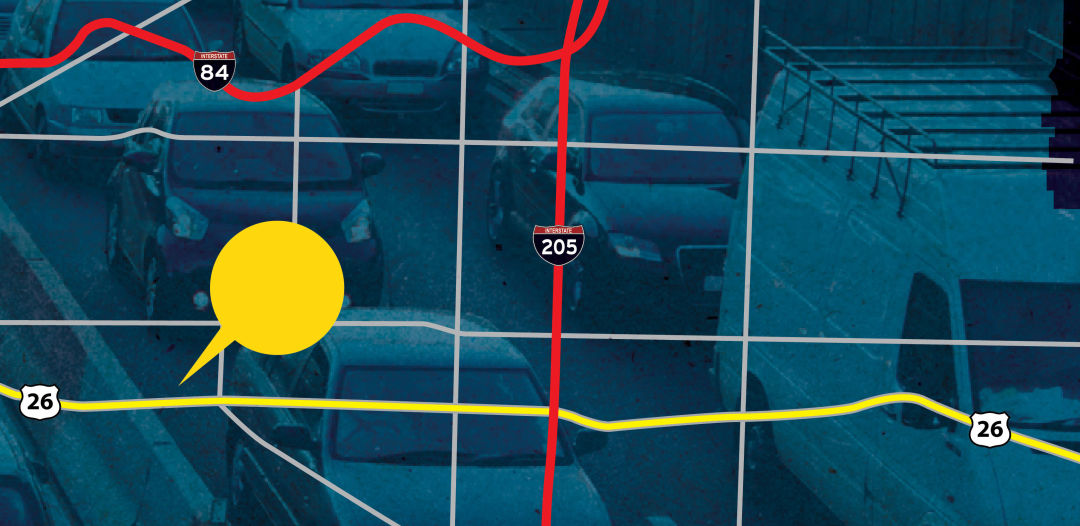

ROSE QUARTER

Pressure point: Apocalyptic congestion near the interchange of I-5 and I-84

What’s being done: ODOT plans to add auxiliary lanes in each direction, though the timing is unknown. “Expanding the roads is enormously expensive,” says Hamilton. True, that: projects adding lanes to I-5 around traffic hellhole Tacoma, Washington, have a reported combined price tag of more than $420 million.

GATEWAY/NE 99TH TRANSIT CENTER

Pressure point: The MAX Blue, Red, and Green Lines have all run through Gateway for a long time, but the area remains unsafe and difficult to access for pedestrians and bicyclists.

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: A new neighborhood greenway will link Gateway to the Sullivan’s Gulch trail. “It’s an area that has really good transit service, but without all the complementary infrastructure,” says Pearce.

SE POWELL BLVD/FOSTER RD

Pressure point: An unusually high number of bike accidents, including two highly publicized ones in May 2015. “It’s a very, very busy area,” says Hamilton, “and it goes right by Cleveland High School.”

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: A federally funded project will change the Foster-Powell junction from a four-lane to a three-lane, increase visibility, and add bicycle facilities. The hope: transform SE Foster from a thoroughfare into a slower-paced main street, like lower E Burnside.

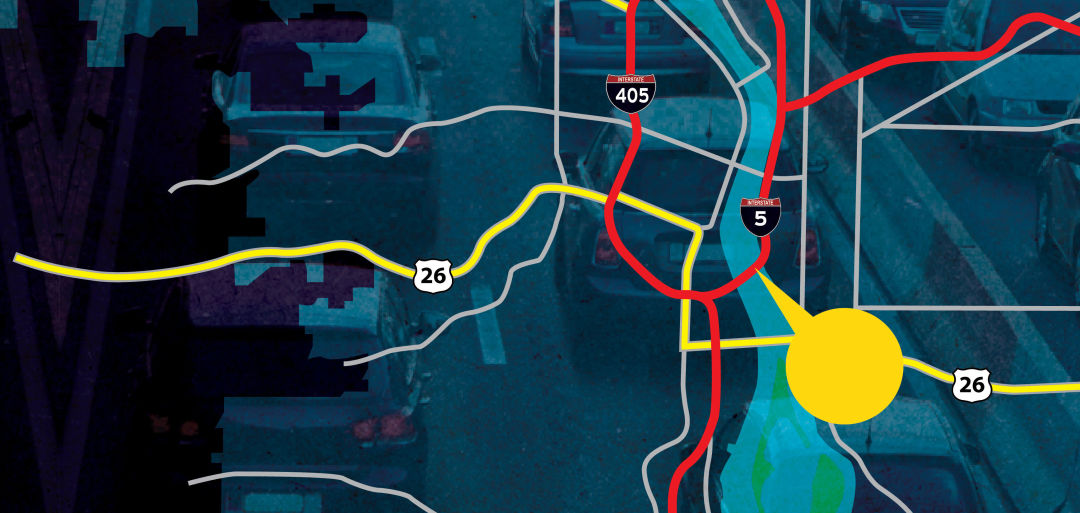

I-5 S/MARQUAM BRIDGE/I-405 S/US 217

Pressure point: High-speed, high-traffic corridors with a high frequency of fender benders

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: ODOT is installing RealTime signs—those big electronic signs that display travel times, advisory speed limits, and road conditions. Explains Hamilton: “The advisory speed indicates there’s a crash ahead. Any time we can decrease the number of secondary crashes, there are fewer significant delays. On 217 in particular, we saw a 20 percent reduction in the number of secondary crashes after we installed those signs.”

I-5 N FROM WILSONVILLE

Pressure point: High congestion due to the volume of traffic merging in and out—known in highway-engineer parlance as “weave”

Image: Artens; Rainer Lesniewski

What’s being done: ODOT is building on-ramps and off-ramps with auxiliary lanes between them. “You have a lot of traffic getting onto I-5 in one lane and just getting off at the next exit,” says Hamilton. “So if you add one ramp going from one to the other, you avoid people having to merge, and merge back to get off. We take the pressure off the mainline.”