You’ve Heard of Scalia. But Who’s O’Scannlain?

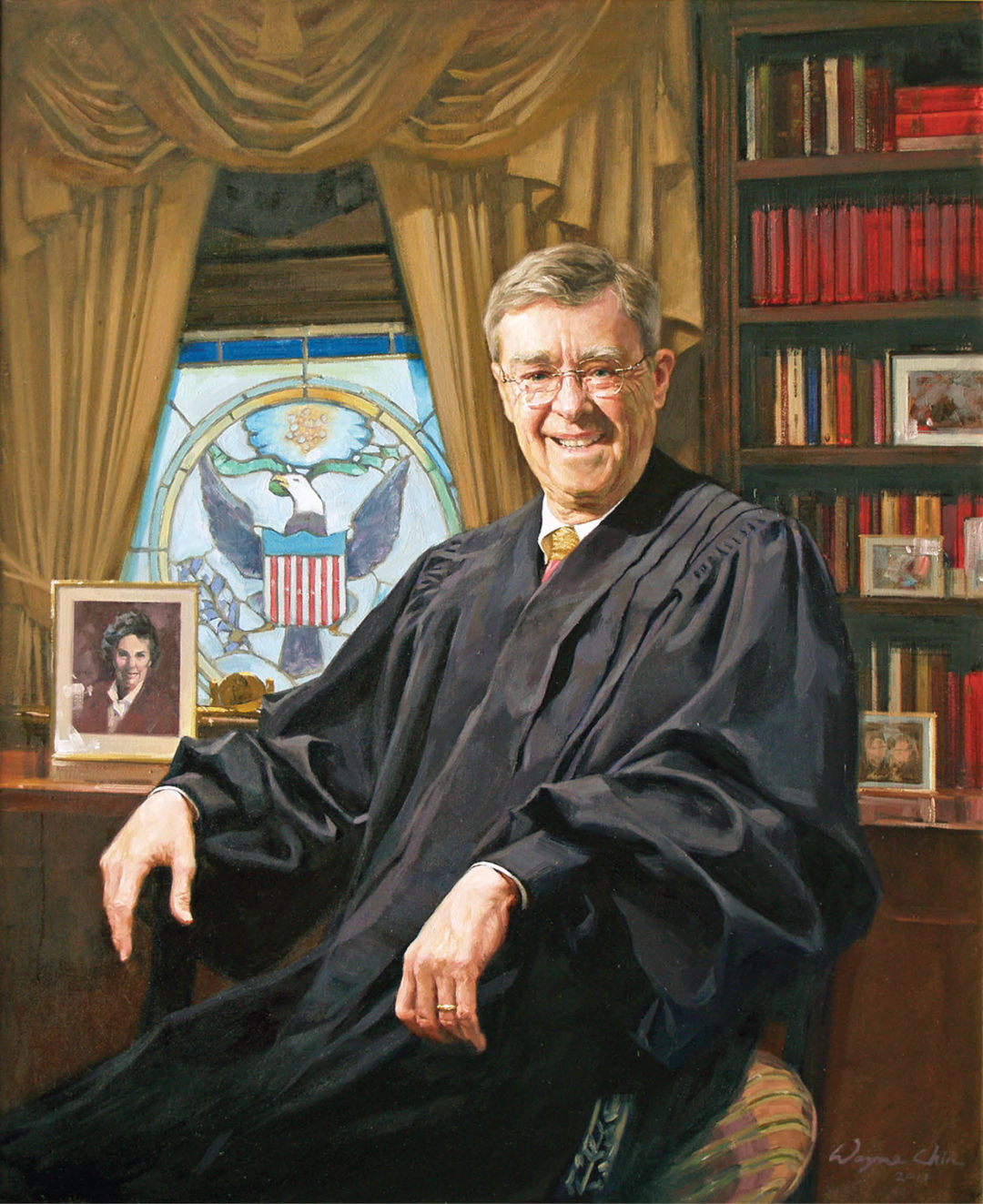

Diarmuid O’Scannlain in an oil portrait, supplied by his chambers

Image: Courtesy Wayne Chim

Ask Portland-based federal appellate judge Diarmuid O’Scannlain what he’s most proud of after nearly 30 years on the bench, and he’ll pull out a blue and red bar chart. The chart lists the names of the judges with whom he has served on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Blue bars show how often the US Supreme Court agreed with an opinion written by each judge; the red, how often the Supremes disagreed.

Out of 59 judges on the list, O’Scannlain’s blue line stands tallest of all. The rightward-tilted Supreme Court of recent times has been on his side, and vice versa.

The February death of Antonin Scalia threw the nation’s highest court into ideological limbo, with Republican leaders vowing to block Merrick Garland, President Obama’s nominee as of press time—or, for that matter, any other Obama nominee. The stakes are high: Scalia was the living symbol of a conservative movement that has remade the American judiciary. Though his name (it’s pronounced DEER-mid, by the way) is not nearly so well known, O’Scannlain has established a nationally significant stronghold of this movement in Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse. From the land of legal cannabis and vegan strip clubs, the 79-year-old figures as a respected—and, naturally, controversial—voice of the judicial right.

Ironically, conservatives love to hate the Ninth Circuit, which sits one tier down the federal judicial hierachy from the Supreme Court. Long considered the most liberal of the regional circuit courts, the Ninth takes cases from nine western states and two territories. The Supreme Court often overrules its published opinions. (Hence, on O’Scannlain’s chart, big red bars for most of his colleagues, as opposed to his tower of blue.)

“I believe the role of the federal courts is to decide cases, not to engage in social policy,” the judge says. That’s roughly what Scalia believed, and a sentiment that surviving high-court conservatives, like Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, would likely endorse. O’Scannlain has influenced more than a generation of lawyers sympathetic to that philosophy, while developing a pipeline to the highest court in the land. Eighteen of his law clerks have gone on to clerk for Supreme Court justices—eight of them for Scalia—making him one of the nation’s top “feeder judges.” It’s a high honor to clerk for a Supreme Court justice, and for a judge to watch so many former protégés land a job that’s a training ground for the elite. (Three current US senators served as Supreme Court clerks, including presidential hopeful Ted Cruz.)

In part, O’Scannlain owes this influence to his role as a pugnacious minority voice within the liberal Ninth. For example, when his colleagues left intact a ruling overturning a gay marriage ban, O’Scannlain wrote a lengthy dissent. When the court ruled that a company involved in a lawsuit over an AIDS drug could not summarily reject a gay man from the jury, he did so again.

Written dissents don’t just express disagreement; they can also give useful signals to the Supreme Court. In 1996, for example, O’Scannlain dissented from his colleagues’ decision that a Washington state law banning physician-assisted suicide was unconstitutional. The nation’s highest court ultimately followed the reasoning in O’Scannlain’s dissent. That happened again in one particularly polarizing case, in which he wrote that Seattle Public Schools could not use a “racial tiebreaker” in assigning students to schools. (Seattle, along with scores of other districts around the country, relied on such policies to promote integration.) The full Ninth Circuit disagreed, but the Supreme Court hewed to O’Scannlain’s analysis. The New York Times called it “a sad day ... for the ideal of racial equality.” The ruling helped set parameters for school districts nationwide.

A sharp, friendly presence during a reporter’s visit to the courthouse, O’Scannlain figures he’s weighed more than 11,000 cases, about issues as fraught as gun rights, free speech, affirmative action, physician-assisted suicide, and cyber law.

“Our job is to protect the rights that are given us under the Constitution,” he says. “It’s following the text of the Constitution and the statutes, and resisting the temptation to read into language and thoughts that really aren’t there.”

O’Scannlain grew up in New York, the son of immigrants, speaking Irish. He graduated from St. John’s University and Harvard Law, and in the early ’60s was active in Young Americans for Freedom, an alliance of young conservatives and libertarians associated with William F. Buckley Jr. that’s often credited as a force behind the conservative remaking of American politics. Later that decade, he moved with his wife, Maura, to Portland. He quickly established roots here, working at several firms and also in government, as deputy attorney general and director of the Department of Environmental Quality. Active in Republican politics, he ran unsuccessfully for a US House seat in 1974. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan tapped him for the federal bench, a lifetime appointment.

In the course of this long career, O’Scannlain has garnered respect across ideological lines. Justice Anthony Kennedy—often the Supreme Court’s moderate swing vote—said just a few years ago that O’Scannlain’s opinions exhibit “a logic, a lucidity and a fairness ... that [demonstrate] the very best in our legal system.” His path also underscores why Scalia’s vacancy has ignited such partisan passion: federal judges stick around for a long time. Though he’s been eligible to retire for more than a decade, O’Scannlain says he’s not planning to quit anytime soon.

“I was issued a life sentence by President Ronald Reagan,” he says, “and I’m to do my best to serve out the term.”