How the Father of Oregon Agriculture Launched a Doomed Quaker Sex Cult

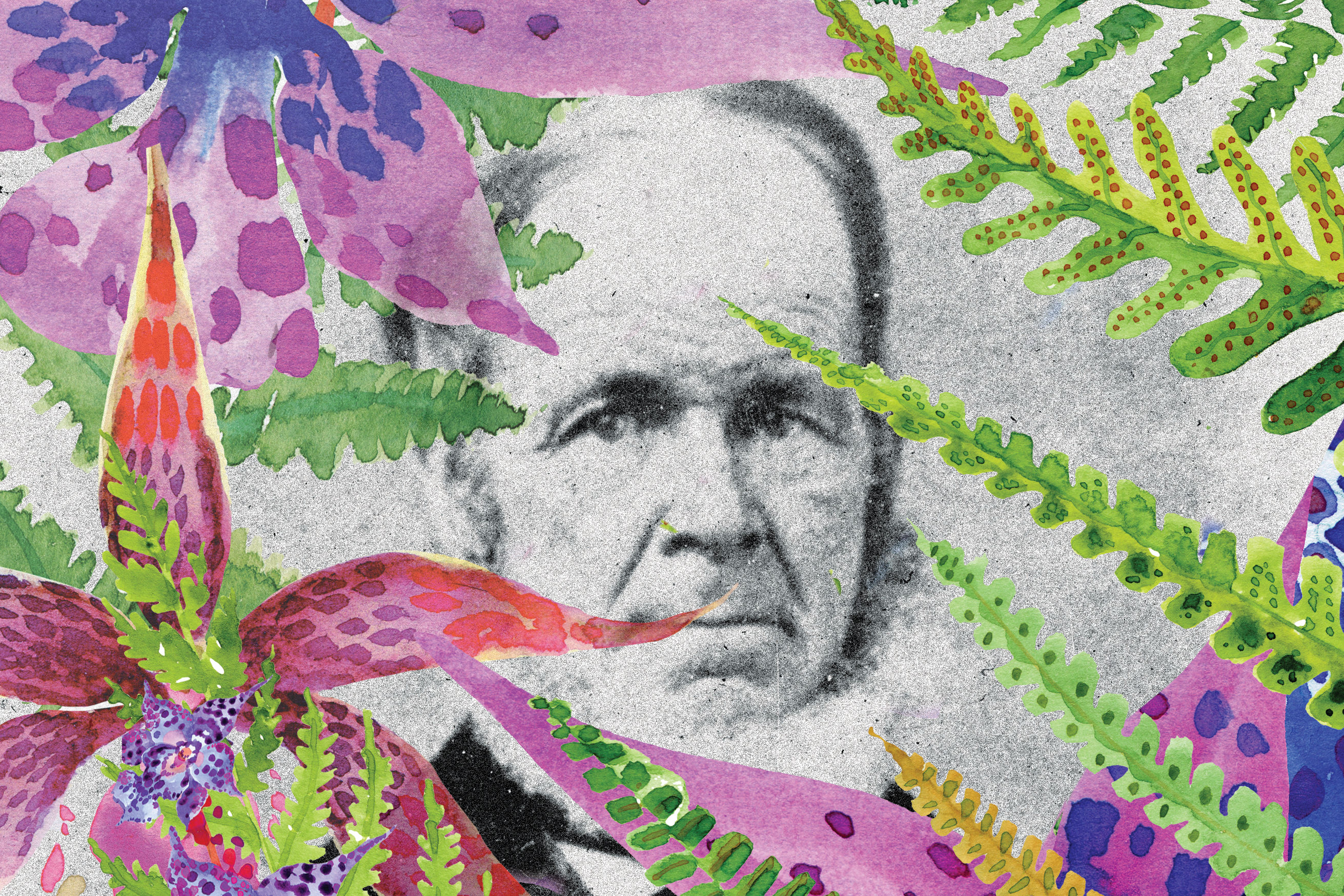

In 1847, a Quaker abolitionist named Henderson Luelling was stricken with Oregon fever, just like thousands of others who abandoned their lives in the settled East or Midwest for greener, more westerly pastures. But Luelling uprooted his Iowa fruit nursery and brought it with him: he packed one wagon with humus and charcoal, and laid in 700 of his strongest saplings. (It was an insane plan with little chance of success. Everyone mocked him for it. He did it anyway.) He hitched three oxen to the heavy wagon, and Luelling’s Traveling Orchard, as it came to be known, was off, joining the 100-plus wagon train of Lot Whitcomb, who would go on to found Milwaukie, Oregon.

Upon arriving, Luelling, his wife, and eight children soon found available land just south of today’s Sellwood, in the present location of Waverley Country Club. The nursery they created became the site of several horticultural milestones: the first spot west of the Rockies to grow prunes and perform tree grafting; the birthplace of the Bing and Black Republican cherries. Some of Luelling’s heirloom fruit trees still stand there.

Within a few years, the orchard and its offspring had produced 20,000 boxes of fruit—one year’s yield was worth the equivalent of $11–17 million in today’s market. One horticulturalist later claimed Luelling’s fruit “brought more wealth to Oregon than all of the ships entering the Columbia River.” His nursery wasn’t just big business; it helped Portland climb out of San Francisco’s shadow as a major West Coast city—much of his fruit was shipped to SF during the gold rush—and cemented Oregon’s status as a fruit king of the West.

But Luelling wasn’t satisfied. In 1854, at age 45, he ditched Oregon for California, lured by its weather, wide-open space, and ostentatious fruit prices. He sold his Portland holdings to his brother and son-in-law, and left to start apricot and cherry orchards in his very own town of Fruitvale, outside Oakland. The settlement thrived, and his wealth grew.

But still, the pioneer orchardman wasn’t content. He recalled an earlier trip he’d taken over the Isthmus of Panama. He contemplated various spiritual truths. Henderson Luelling started getting ... ideas.

It was a time of big ideas. The mid-19th century had seen a surge in socialism, reformism, and alternative spiritualities, especially among wealthy progressives. Luelling was a Quaker, but in Oregon he’d begun dabbling in eccentricities like Spiritualism—a hugely popular and influential movement founded on the conviction that the living can communicate with the dead. (If you’ve used a Ouija board, you’ve felt Spiritualism’s vibrations.) During this time, various threads of utopian socialism also emerged, intertwining Spiritualism—which, among other things, challenged the era’s established churches and thus appealed to those with radical leanings—and free love.

Spiritual communion was believed by free lovers to supersede legal marriage, which they saw as a type of sexual slavery against women. They argued, not to put too fine a point on it, for an individual’s rights to bang anyone they fancied—to couple and uncouple at will. Freeing sexuality from marriage was not only emancipation, but an early example of women’s liberation. Allusions to abolition and feminism (among other things, surely) made free love interesting to Luelling.

And that’s why, just five years after leaving Portland, he sold Fruitvale to the governor of California for $40,000 (more than $1 million today), bought a boat named Santiago and 50,000 acres of rain forest, and joined a religious sex cult bound for his tropical island.

On October 8, 1859, the Sacramento Daily Union reported: “An association of Free Lovers, known as the Harmonial Brotherhood, sailed for San Salvador this afternoon, in the schooner Santiago. They number about twenty-five persons, male and female, and are under the guidance of Dr. Tyler. They propose to settle in the interior of Honduras.”

Luelling had taken up with these groovy Free Lovers, whom he met in San Francisco. From the outset, the journey had complications. “Dr.” Tyler, it turned out, was actually an ex-blacksmith who now professed expertise in water-cures and clairvoyance. One of the men was fleeing financial troubles, and when the ship was searched by police he hid under the hoopskirt of a female passenger. The teenaged daughter of one of the emigrants threatened to drink a vial of strychnine if forced to join them.

The one who caused the most delay, however, was the group’s “chief man,” Luelling. He decided to leave his wife behind, leaving her no choice but to file a de lunatico inquirendo against him, initiating a formal investigation of his sanity. To avoid her, Luelling laid low for a couple of days after the vessel left the wharf, then hopped on a little boat and joined the schooner once it passed out of the San Francisco Bay.

There was constant bickering, especially between Luelling and Dr. Tyler, leading the Santiago’s crew to nickname the colonists the “Discordant Devils.” Time at sea tested not only the sensual pilgrims’ patience, but their principles as well. Several of the colonists quickly abandoned their vegetarian diets, sneaking salt pork and coffee on the boat and straight-up eating fresh beef and game when ashore—another point of conflict.

Then came the “egg war.” In Oaxaca, a seller approached with several dozen eggs for sale, and Luelling bought them all. Not realizing the eggs had already been purchased, Dr. Tyler, too, bought them all. (The egg hawker was surely delighted to have been paid twice.)

The eggs were the last straw.

The Daily Union reported the resulting squabble arose “like a spark of fire in a pile of dry shavings; the flame increased and spread.” The fight continued for days; finally, Luelling called a meeting to try to address “the egg question.” He made a grandiose speech which said he was “directed by the most highest wisdom and came from the interior essence of his soul.” Dr. Tyler accused Luelling of exploiting everyone and promised he’d get even. The others on the ship got involved, too, taking sides and talking smack. “You’re no lady!” one woman lobbed. “Liar!” another shrieked in return. The crew of the ship complained they were in “Free Love Hell.”

Finally, the travelers made it to Luelling’s (sadly, tiger-free) Tiger Island, a small scrap of Honduran volcano in the Gulf of Fonseca, arriving in the fall—purportedly the best time of year in Central America. Their vegetarianism wasn’t as effective as they’d boastfully predicted at preventing tropical diseases, however, and several immediately got sick. Unfortunately, the Free Lovers subscribed to fashionable hydrotherapy rather than modern medicine. One lady ran a high fever; they cocooned her in wool blankets until she began sweating profusely, and then threw a bucket of ice water on her. (Water-cures aren’t the greatest idea when the water’s full of cholera.) “The speedy result was her death,” reported the paper.

Before the ship could even turn around to leave, two people had died, half a dozen more were sick, Dr. Tyler and his wife had seceded from the colony along with several other members, and the rest were waiting for their chance to get the hell out of there. Between the bad water and the humidity, it turned out that Honduras was a lousy place for a bunch of wealthy vegetarian swingers to start a sex cult.

Luelling returned to California, destitute and defeated. It was the first time one of his harebrained schemes had failed, and he struggled to bounce back. The Santiago wrecked in Mazatlán during the return to San Francisco in July 1860, so he didn’t have a ship anymore. He struggled to reenter the fruit biz; he had a falling out with his brother. In 1878, Luelling was found “dead and partially roasted” after he suffered a heart attack while clearing land for another orchard in San Jose. His body was discovered prone, with the field burning around him, his hair and beard singed off, clothes still smoldering.

In the strange days of 2018, it’s tempting to think our era invented social aberration and spiritual wanderlust. Wrong. In 1881, one emigrants’ guide to the United States advised would-be Americans on the range of freedoms they might expect in this new world—with the caveat that one also must contend with “the Spiritualists and the Shakers, the Mormons and the Mennonites, the Free Lovers and the Thinkers, and every other species of religious idiosyncracy that a diseased imagination can organise. They spring up and live their little day, and suddenly wither under the influence of science and common sense.”

Oregon always seems to be either first or last stop for these eccentric radicals and telekinetic vegetarians; those who want to free their minds and let their asses follow. Fred Meyer was a Rosicrucian, part of a mystical spiritual order devoted to “natural law”; Abigail Duniway was friends with a psychic medium. It’s no surprise the father of our fruit industry was obsessed with talking to ghosts and liberating women via intercourse.

Today, shelved at Multnomah County libraries, there are two kids’ picture books that tell Luelling’s story—Tree Wagon and Apples to Oregon. Neither shares the juiciest details of the life of the free-loving orchardist who just couldn’t sit still.