This Portland Artist Uses Her Own Hair to Explore Race

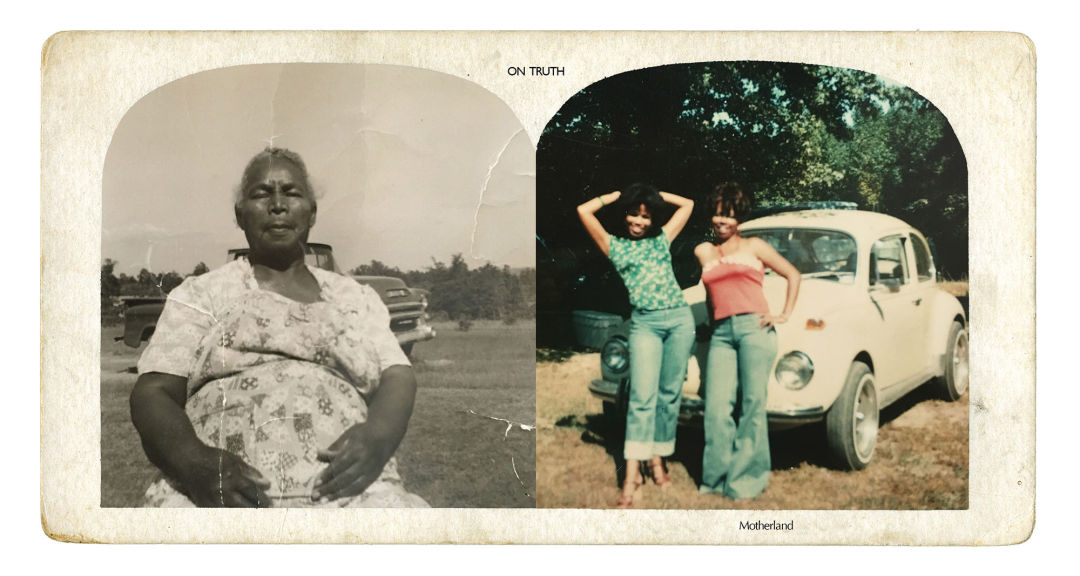

A large-scale photo from Jarrett's collaborative show Future Ancestors

Hair is everywhere: clouds of hair imprinted on large white sheets of paper, a weave on the table, afro combs traced over and over onto pieces on the wall, hairnets emerging from others. This is the studio of Portland artist Lisa Jarrett, and hair is threaded—sometimes literally—through her work. There was 2015’s How Many Licks, a series of clear-wrapped, homemade lollipops with Jarrett’s own hair spidering from their sweet centers. She followed that with last year’s Imagining Home, in which she invited participants to use the same wad of her hair over and over to create the shapes of imaginary homelands. Hair shows up again this month in long, thick braids and copper twists, a touchstone in the vivid, large-scale photography of her collaborative show, Future Ancestors, at Ori Gallery.

Hair as muse and subject appealed because, says Jarrett, “I already had all the knowledge. I spend umpteen hours combing this. It’s part of my integrated life.” Through hair-made art, she has found a route to process “ideas around identity and race and difference.”

A lollipop encasing some of Jarrett's own hair

Image: Courtesy Lisa Jarrett

Jarrett, an assistant professor of art practices at Portland State University, plays two powerful roles in Portland’s artistic ecosystem: the New Jersey native is one of the city’s most potent and astute art makers, described as an “emotional wizard” by fellow artist Samantha Wall, and was recently awarded a prestigious grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation. But Jarrett also pushes her work on race and representation beyond the gallery, joining and helming projects centered in local communities, most prominently as a cofounder of KSMoCa, an art museum inside a Northeast Portland school. As Jarrett tells it, her gallery art and outreach initiatives—from lollipops to grade schoolers curating artwork—are all part of the same practice.

KSMoCA, created with her PSU colleague Harrell Fletcher, lives at Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary, a majority-nonwhite public school in the heart of rapidly gentrifying Northeast Portland. The museum began in one room in 2014, but soon became a schoolwide project—a gallery space that invites students to become curators, choosing the work for display, interviewing the artists, creating signage, and placing the art. It has included pieces from multimedia artist Wendy Red Star, illustrator Carson Ellis, and Brooklyn-based graphic artist Chitra Ganesh.

“Who goes to galleries and museums? Why do only particular groups feel welcome?” These are questions Jarrett explores with the initiative, working with artists “that show you a different picture of who participates in the art world.” What Jarrett brings to the project, says Fletcher, is a rare combination of people skills and artistic knowledge. “When we go there and walk through the halls, kids are always [coming] up to her and hugging her, calling out her name,” he says. “She has an incredible rapport with the community at the school, but also has knowledge and interest in contemporary art.”

The projects in schools—she and Fletcher also work with students from Harriet Tubman Middle School on curating and critical engagement—have had a profound effect on Jarrett’s gallery efforts. “It has dramatically changed how I approached my work in general,” she says. “The work that’s happening in the community that’s socially engaged, ties you to a community. And I feel really responsible to that work.”

For Jarrett, the gallery work—a hairnet embedded on paper, continents created from her own hair—may urge the viewer to alter their perspective on an everyday object and reframe thoughts around how race functions within that perspective; but, she says, “working in a social practice fashion allows me to participate in those ideas in a really active way that engages youth, that engages elders, and engages the actual institutions that I’m curious about.”

Such explorations continue in Future Ancestors. The show emerged from Art 25, a collective she cofounded with the queer writer and artist Lehua M. Taitano that led the duo to Oahu, Hawai’i to collaborate with Honolulu artist Jocelyn Kapumealani Ng. The resulting works are striking: giant, deeply hued photographs of Jarrett and Taitano in intimate conversation, faces painted with metallic accents, bodies draped in feathers and ropes. The images are accompanied by audio pieces that tell the stories of the characters each artist portrays. “We wanted to think about imagining ourselves as future ancestors and physically transforming into those people now,” says Jarrett. Hair, once again, is integral, in this case in her representation of herself to future generations.

Images from Jarrett's 2018 series Reconciliations, which were framed with tufts of hair below them

Image: Courtesy Lisa Jarrett

A clear connection to her fellow artists runs through the show—captured in one affecting image as a literal embrace. It’s the same empathy she brings to her work with students, with the elderly in her contribution to the People’s Home Project, which paired local artists with longtime Portland residents to illustrate their concept of home, and with the audience for her art. “The things that matter to us we find mirrored within her work,” says Wall, who says that gift is directly

related to Jarrett’s empathy. “That’s a special thing. Not many artists can do that.”

Future Ancestors

Oct–Nov 30, Ori Gallery