Author John Birdsall on James Beard's Gay Identity and Oregon Roots

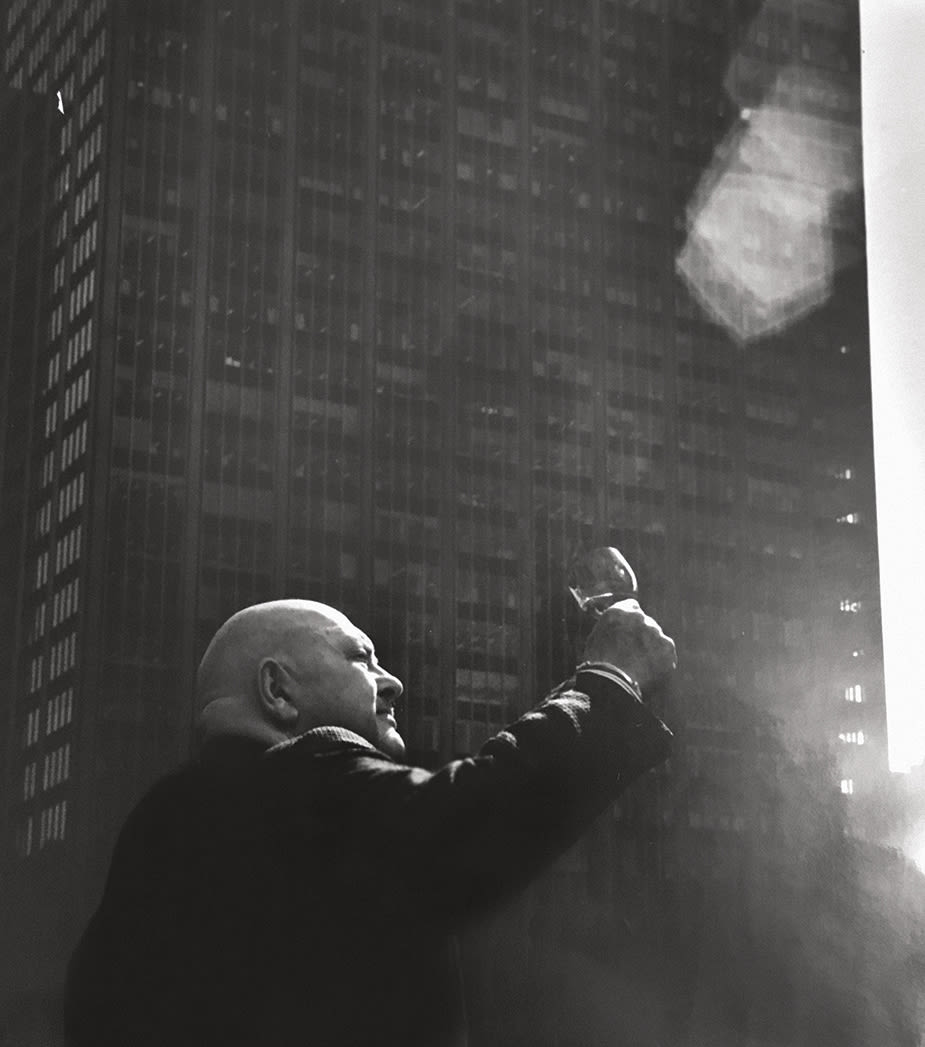

James Beard in New York

Image: Courtesy Eugene Cook

Behind his dozens of cookbooks and his authoritative status as “The Dean of American Cookery,” Portland-born food writer James Beard hid the fact that he was gay, a facet of his life known only to his inner circle and hidden for years even after his death.

Author and former chef John Birdsall writes that before Beard died in 1985, he entrusted friend and fellow cookbook author Marion Cunningham “to clear out and destroy any last incriminating papers in [his] house—anything gay, an indiscreet letter he might have overlooked and failed to destroy himself—a stray magazine, something to trouble his legacy or

embarrass his friends.”

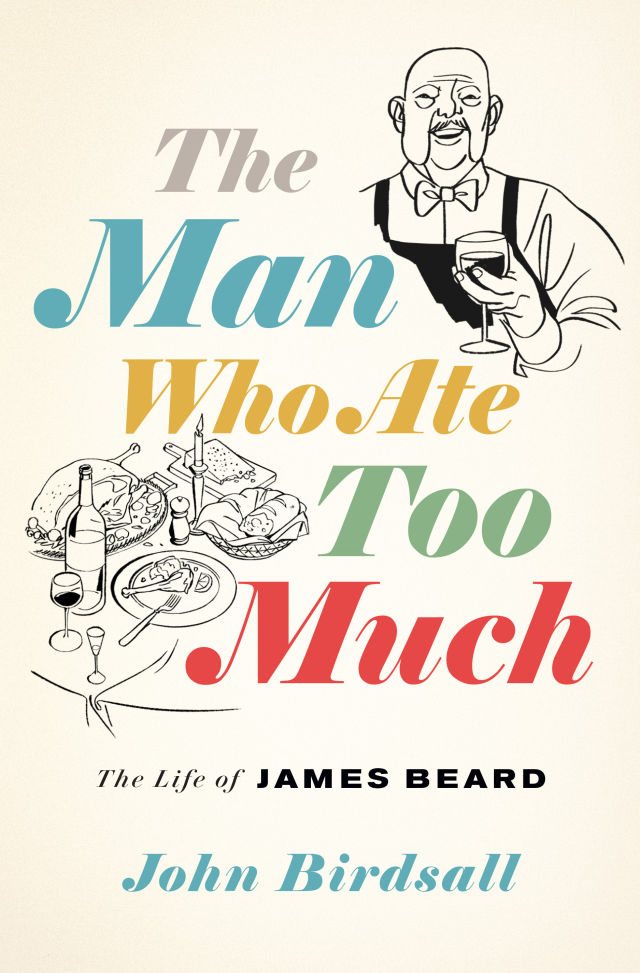

The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard

In The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard (out October 6 from W. W. Norton, $35), Birdsall offers a compassionate, honest, and meticulously researched take on how Beard became one of the most influential figures in American food while concealing this important part of his identity. In the first biography of the American food writer and TV personality written in 25 years, Birdsall delves into Beard’s youth in Oregon, where he fell in love with fresh ingredients like razor clams from the beaches of Gearhart.

He also discusses Beard’s expulsion from Reed College for having an affair with a male professor in 1921, at a time when anti-gay sentiment was rampant in Portland and a gay man could be forcibly sterilized under Oregon law. He details Beard’s career in New York City, exploring how his sexuality shaped American food as we know it. In a conversation with Portland Monthly, Birdsall discusses his process, his fascination with Beard, and Oregon’s indelible mark on the iconic chef—and in turn, the rest of the country.

On his decision to focus on James Beard: It started with a piece I wrote for Lucky Peach print magazine in 2013 called “America, Your Food Is So Gay,” [about] the hidden, unacknowledged influence of closeted gay food writers in the 20th century. It won a James Beard award the following year.

Beard and family at their home on SE Salmon Street in Portland.

James Beard really struck me as someone who had, first of all, a tremendous influence on American food in the mid to late 20th century. And I was fascinated: how could someone who was closeted, except for a small circle of New York food editors, how could that person also be a household name in the United States? I wanted to know how Beard’s experience as a gay man who had to be really careful about his identity, what that did to his food since his food was acknowledged at the time as the quintessential American food.

On his research process in Portland and on the Oregon coast: There’s a chunk of Beard archives at the Oregon Historical Society. I took a couple of trips out to the coast to look at Gearhart, where James and his mother would spend summers at the cottage. Obviously walking to the beach, which was a huge influence in James’s life, [and] spending some time in Astoria. I also got to go to Seaside High School, just south of Gearhart, [where] in the 1970s, for about six or seven years, James would teach monthlong cooking classes in the home-ec kitchen.

On Beard’s expulsion from Reed, which haunted Beard for years, and Reed’s decision to grant Beard an honorary degree in 1976: As far as my research goes, [Reed] never acknowledged that that’s why he was expelled. Officially, it was because of his studies—“insufficient scholarship” was the phrase that explained why he had to leave.

Beard’s classmates and professor at Reed College.

I know that James was very moved by [the honorary degree]. I think some of his friends who knew the real story were kind of scratching their heads thinking, “Hey, why would you want to go back to this institution that had turned you out for something as essential as being who you are?” But he definitely saw it as a reconciliation. He really saw himself as a westerner, and he felt that Reed’s ideals were really his ideals, that it was an open, progressive, democratic institution. It was not about elitism, it was not about snobbery.

Understanding the dynamics of it in 1921, I believe that [the expulsion] was in a way a progressive act, and really in some ways, a compassionate act, to allow James to expel himself without calling the police, without involving the authorities, kind of taking care of it quietly.... I can see Reed was in a difficult position.

On the way Oregon shaped Beard’s focus on fresh, local ingredients at a time when frozen TV dinners were all the rage: Portland—and especially the coast—imprinted so strongly on him this idea of food, all the things that would later become clichés: that the best food is local, that it’s grown nearby. Really, you can see the foundation of the farm-to-table movement in James Beard’s work.

Beard with other members of the food media in Greenwich Village.

Image: Courtesy Jonathan Ned Katz

All of Beard’s life, American food was trending in exactly the opposite direction, that it was really large food corporations that were writing, sometimes under fake names like Betty Crocker, corporate recipes meant to sell corporate food products. Beard definitely counters that by coming up with this narrative based in Oregon, based in Portland, that Americans’ [reliance] on supermarkets has really given up one of the great pleasures available to them, which is food.

On Beard’s wish to have his ashes scattered in Gearhart despite spending most of his adult life in New York City: That area [of Oregon] in particular was always in his mind. He would complain about how unsophisticated food in New York City was, that it was about conspicuous consumption, that it was about having the right table in the right restaurant, and he really loved food that was delicious but not pretentious. He saw Gearhart and the coast as being this place of authenticity, both in the food and as a place where he himself felt that he could be more authentic.

On what Birdsall would cook for James Beard if he could have him over for dinner: I would want to cook him something very, very simple. Something large and meaty—maybe a leg of lamb cooked really, really pinky-red, the way he liked it. The guest list would be the kind of queer people he would like and feel comfortable with, the kind of circle that he cultivated himself, where he could be relaxed. He wouldn’t even have to talk about food.