Food Cart City

Addy Bittner slices a slender baguette, arranges about a dozen small, dark-chocolate discs (73 percent cacao) on the bread’s pillowy face, adds a drizzle of extra-virgin olive oil and a dash of salt, then tucks this meth-caliber assembly of bread, sugar, caffeine, and love into a small oven. A twist of the knob and… power failure.

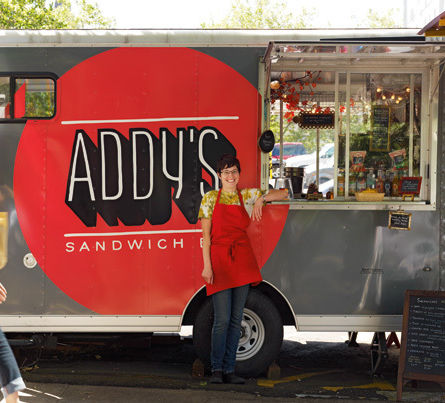

Bittner’s sprightly gray, black, and red food cart, labeled "Addy’s Sandwich Bar" with a distinctly Parisian flourish, is parked amid one of downtown’s busiest food cart "pods"—the corner of SW 10th Avenue and Alder Street. As she vaults over stacked cardboard boxes to reset her circuit breaker, Bittner, sporting a shaggy pixie haircut, all-black canvas sneaks, and a worn-in Blazers T-shirt, neatly encapsulates Portland’s newest brand of restaurateur—as played by Audrey Tautou. Her electricity may fail, but her duck confit and house-made country pork pâté rule.

Addy’s Sandwich Bar could be a metaphor for the whole city.

Less than a decade ago, a Portlander who frequented one semi-sanitary burrito truck could smugly feel like an urban insider. Today, Multnomah County licenses more than 300 food carts. Within 100 yards of Addy’s alone, pavement gourmands can savor Korean tacos, first-class espresso, and walloping Bosnian pitas. A half-dozen gyro options jostle with a week’s worth of banh mi choices. Cult-favorite pork yakisoba competes with single-dish purveyors of Bangkok street delicacies. One newcomer promises "anything you can stuff in a dumpling."

No one planned Portland’s cart revolution. In a city that tends to workshop and white-paper every last particle of its existence, "the carts" are a rare local instance of Taoist urbanism. And in the process of letting them happen, the city stumbled upon a form of kudzu capitalism—powered by propane tanks and makeshift wiring—that reclaims and revitalizes vacant land. Portland’s food-cart phenomenon couples the city’s obsession with gastronomy and a dirty-fingernailed, DIY brand of free enterprise. It’s the perfect combination for the dynamic talent this city attracts, and for our gloomy economic times.

Addy Bittner in front of her popular sandwich cart at SW 10th Avenue and Alder Street

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

So now what? With downtown’s pods bustling, and new carts propagating across the East Side, do we just let this benign anarchy grow unchecked as far as it will? Or should we play around with new ways to harness this spontaneous expression of urban vitality (and chocolate-sandwich lust)?

Back in the 1970s, faced with a dying downtown, Portland declared that all center-city construction had to include ground-floor retail. It was a good idea, and one that injected new energy into our streets. But as the recession has filled many a city code–commanded storefront window with "FOR LEASE" signs, it’s the once-barren—and oft-ridiculed—surface parking lots that have begun pulsing with urban life in the form of food carts.

"The carts’ success downtown has people thinking of these sorts of structures as an interim form of development that can create a destination," says Marcy McInelly, an associate principal at Sera Architects. "Traditional restaurants do that, but it takes a long time. Carts can do it very quickly."

City Center Parking, a firm owned partly by the powerful Goodman family, rules acres of downtown asphalt. For decades, many mourned the Goodmans’ reluctance to develop their lots into the sort of high-density, mixed-use new buildings that long ago became urban-planning gospel. Now, economic conditions strongly suggest that new downtown high-rises won’t be popping up anytime soon. Meanwhile, City Center has decided—call it enlightened self-interest—to allow carts to breed on its lots.

"It started with one, basically," says Al Niknabard, City Center’s director of operations. "Then it was two. Then four. And it seemed like the more we added, the better they all did." Niknabard declines to even estimate how many carts now occupy the edges of City Center’s lots. "We hardly ever have cancellations. It will go as far as classical capitalism will let it."

Yet, it’s hard not to wonder: what could a smash-hit cart pod, complete with a cheerful local vibe and a foodie cult following, do for some of Portland’s persistently forlorn neighborhoods? Could an Airstream slinging post-Vietnamese Southeast Asian fusion do more for Lents than any half-baked baseball stadium scheme? Should we just retire the cursed name "Burnside Bridgehead" and encourage every successful downtown cart to open a second location at NE Couch Street and Third Avenue?

Having mastered the art of Belgian-style fries and poutine, Potato Champion (see “Cartopia”) draws late-night cartgoers in search of starches to soak up the evening’s indulgences.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Indeed, hop the river from downtown, and it feels like every scrap of wasteland from SE Kelly Street and 50th Avenue (home to the acclaimed Wy’East Pizza) to N Greeley Avenue and Killingsworth Street (where Venezuelan empanadas commingle with homemade ice cream, see "The Pioneer") is sprouting with carts. A parallel subculture thrives online, where cart zealots track every new opening on websites and Twitter feeds. At its most successful, the cart diaspora creates improvised village plazas where neighbors gather (and spend), generating reams of positive online chatter about a new kind of place—usually a former vacant lot.

McInelly, for one, sees some potential in strategic cart deployment. She and her firm drafted a "best practices" menu for Portland’s transportation office that suggested using food carts to spruce up the East Side’s dour MAX stations. "It’s a way to create a ‘there’ there," she says. "You could potentially use carts at transit stations, or in the Lloyd District—anywhere you want to foster some vitality."

So perhaps advancing the cart revolution requires nothing more than matchmaking. Desperate property owner? Meet moneymaking opportunity. On N Mississippi Avenue, developer Roger Goldingay faced recessionary doom on a vacant lot he bought at the height of the real estate boom. Carts proved his salvation—today, his Mississippi Marketplace knits together 10 high-quality carts with customized water and power grids, all atop eco-friendly, rainwater-permeable asphalt (see "Pod Perfection").

"I think you can say we saved a developer—me—and a contractor, and probably two marriages," Goldingay tells me. "We started 10 small businesses and created 40 or 50 jobs."

And therein, perhaps, lies the true genius and potential of Portland’s carts. In these woozy, hungover years after our binge on fake credit and ersatz profits, food carts bring American business down to earth. On vacant lots and unloved parking strips in Portland, tiny operations demonstrate a different way for free enterprise to take root, grow, and change a city’s streets and tastes.

When Addy Bittner shows up to work every day at 7:30 a.m., she grabs two jugs and heads across the street to gather her day’s water supply from hoses she shares with other carts. When something breaks, she fixes it. And yet, in her own humble way, she’s living the entrepreneurial dream.

"I could totally go for running water," she says. "On the other hand, it’s a microbusiness, and I can do everything myself. I have to do everything myself."

Tour our favorite food cart pods with Karen Brooks, restaurant critic for Portland Monthly magazine and a food cart fanatic.

Find out where to go, what to eat, and what not to miss!