The American Pilot

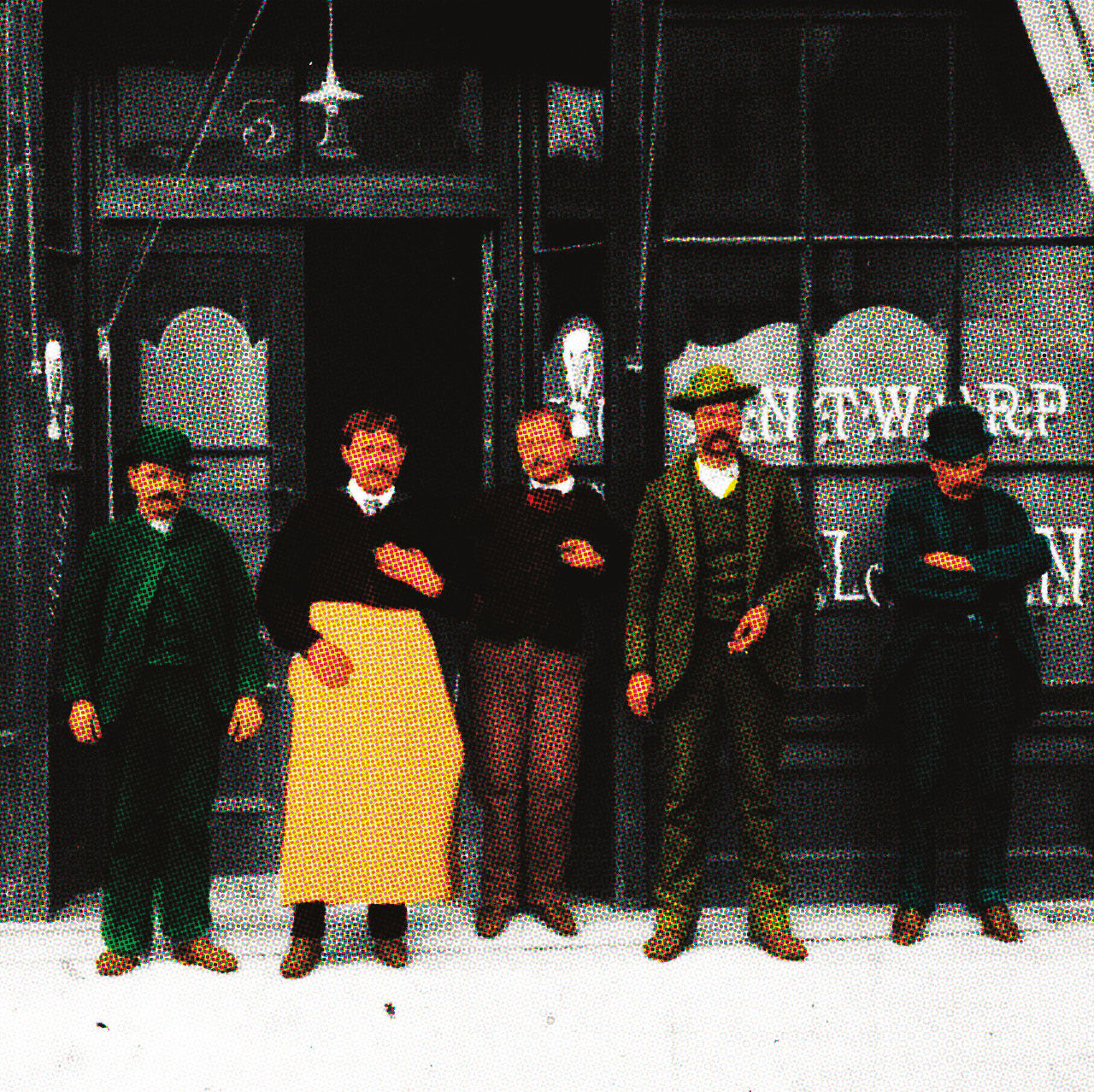

Courtesy of Alan H. Rosenberg, Producer, “A Brief Flight,” Museum of Chinese in America Hazel Ying Lee/Frances M. Tong Collection (cropped and colorized)

October 1944. World War II raged, but Hazel Ying Lee was grounded at Romulus air base in Michigan. She had fallen ill after copiloting a B-24 bomber on a recent mission, and knew that come December, the military planned to ax the program that let her fly. She was anxious for another mission before it did.

Born in Portland in 1912, Lee was a Women Airforce Service Pilot—or WASP—and the first Chinese American woman to fly for the US military. A graduate of Commerce High (present-day Cleveland), Lee, whose immigrant parents met in Portland, grew up constrained by discrimination. But she fell in love with aviation after a ride in a friend’s plane in 1931. That year, Japan occupied Manchuria. The next, Lee (shown on the right here) graduated from Portland’s Chinese Aeronautical School, one of several flying academies Chinese Americans created to support China during its confrontation with Japan.

Lee traveled to China, but military leaders there wouldn’t let women fly in the nation’s air force. (Another volunteer from Portland’s Chinese American flight school, Arthur Chin, became the first American-born fighting ace of the World War II period.) So she took a desk job and flew occasional commercial flights. But in 1938, a year after full-scale war broke out between Japan and China, Lee returned home. After Pearl Harbor, the US needed domestic pilots to replace men sent overseas. Lee volunteered for the WASPs; the noncombat outfit accepted only one in every 25 women who applied. She soon qualified for an elite cadre certified to fly pursuit aircraft—speedy, powerful fighters like the P-51 Mustang—from factories to air bases.

The WASPs were slated to disband at the end of 1944, just after Lee fell ill. She recovered in time for a final mission, but during a landing at Great Falls, Montana, another plane collided with hers. She died two days later; her brother Victor was killed fighting in France at almost the same time. Portland’s River View Cemetery initially refused to bury the siblings alongside white Portlanders, but their sister wrote to President Roosevelt and the cemetery backed down. Because the WASPs were considered civilians, Lee was denied military death benefits. In 2010, she—along with the other 1,073 women who served as WASPs—received the Congressional Gold Medal.

Bill Lascher’s first book, the true story of two World War II journalists who fell in love while covering the conflict in Asia, comes out in 2016.