An Oregon Historian on What We Can Learn From the 1918 Flu Epidemic

In the early fall of 1918, a young private was on his way from Camp Lewis in Washington state to military training in Texas. By the time he got to Portland, he had a raging fever—doctors at a local hospital diagnosed him with the Spanish flu, the first documented case in the city. (In those days, disease transmission routes tended to follow rail lines and the movements of soldiers mobilizing for the war in Europe.) By the end of 1919, some 50,000 Oregonians had been infected, and 3,600 had died—an official fatality rate of about 7 percent (though the actual infection rate was probably much higher).

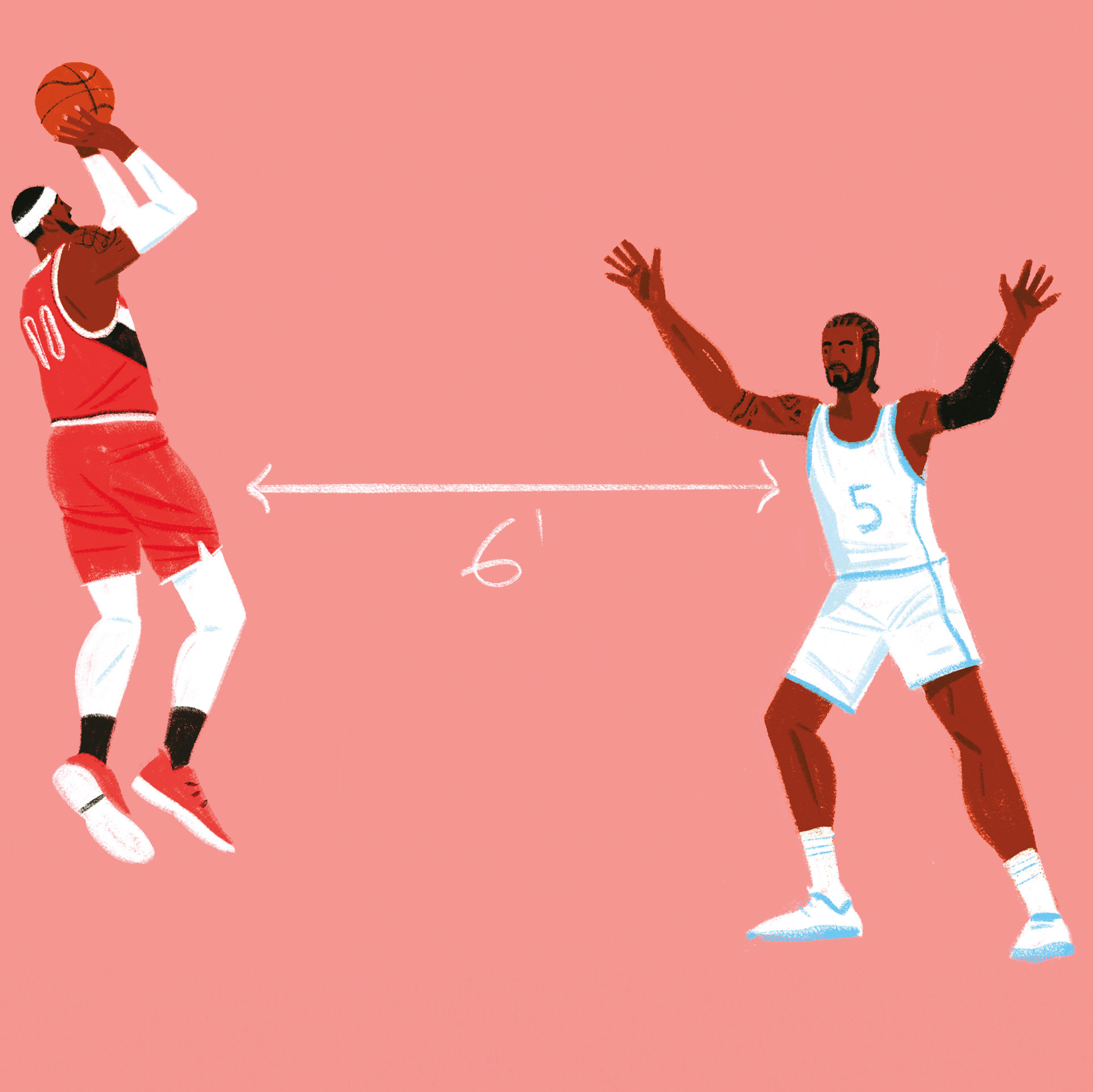

As today, the pandemic’s story was writ globally but decided locally. The Portland City Council, which had advance warning from East Coast cities, moved rapidly and put into place a strong series of social distancing measures, closing schools, theaters, and public gatherings, and requiring everyone to wear face masks. Despite pushback from those opposing Western medicine, Oregon’s response counts as a relative success in a pandemic that claimed 50 million lives worldwide.

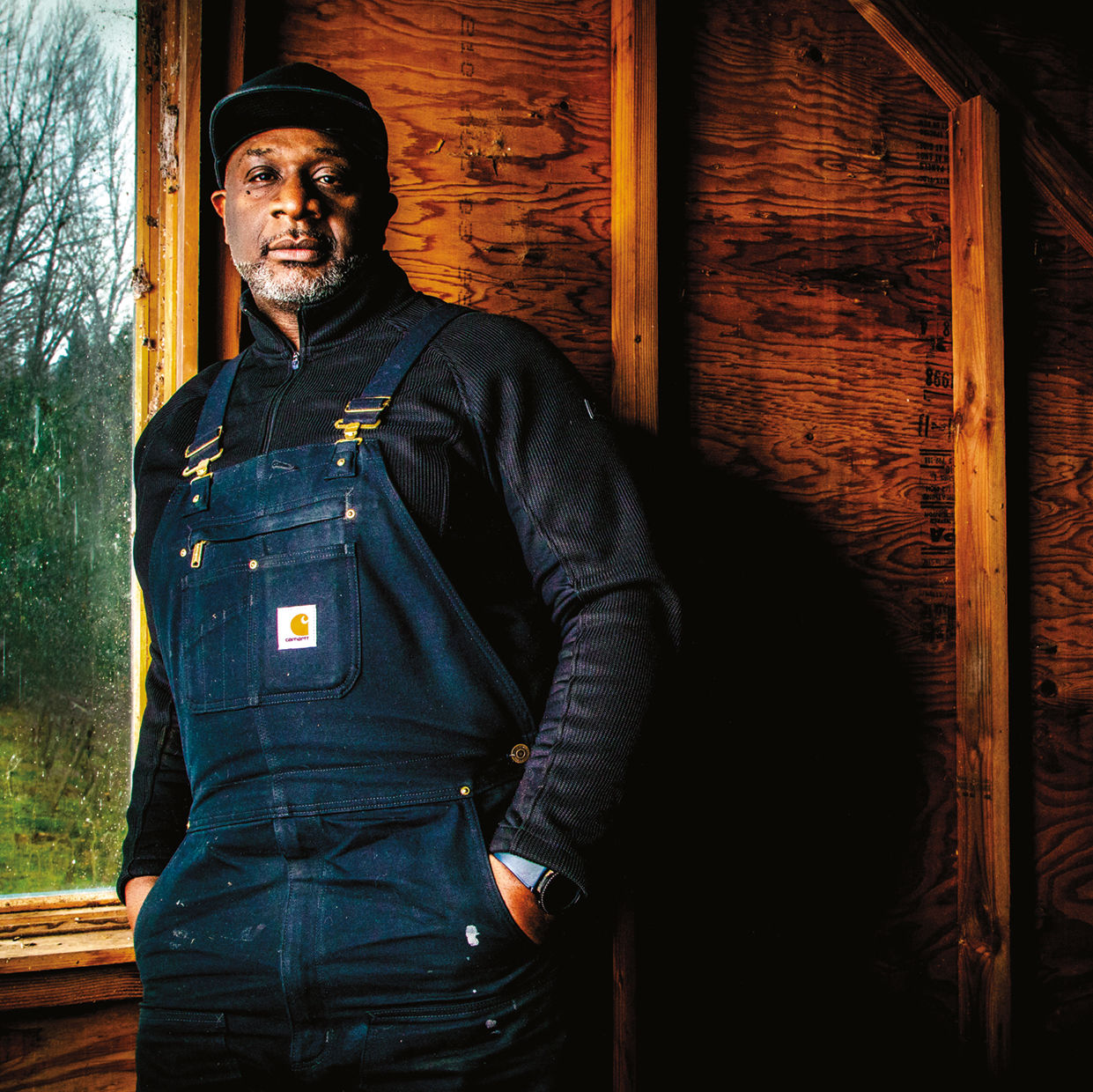

Christopher McKnight Nichols, a history professor at Oregon State University, tells us what we can learn from the past.

Be honest.

“The [Woodrow] Wilson government in 1918 was probably the most powerful centralized government since Lincoln’s in the Civil War. If any government could have had a centralized response, that one could have. They had price controls going, selective service and a draft, they had a war management bureau and a war industrial board. [But the war effort was] partly why the federal government obfuscated and minimized the risks related to the flu outbreak.

“In Coos Bay in 1918, they started running out of child-size coffins. And then the undertaker got the flu, and they just had to start stacking bodies. In a smaller community, that really changes how people think about this. People said, ‘I can’t trust what the government has said, so I’m just not gonna help anybody or I’m gonna watch out for myself.’ And while that might be decent for social distancing, it’s terrible for our communities. Even when the federal government isn’t honest, local and state government can still fill in the gap with trust.”

The cost of inaction far outweighs the cost of action.

“This is a historical truism for pandemics. Pausing, reflecting, obfuscating, lying, or just not being decisive is always a lot worse. Tell the truth, close things down, and do the best you can. That has worked [historically] at the local and state levels. Public health commissioners and officials in lots of small cities across the US in 1918 took the lead on this stuff and saved a lot of their citizens.”

Don’t open up too quickly.

“There’s no doubt—and this is why people study this, from urban historians to those doing history of science to epidemiologists—that rates of infection and death were lower in the places that did radical social distancing and kept things closed longer. Bottom line. Unequivocally. History doesn’t provide simple lessons. But this is one place where it does.”

Be ready for some societal shifts. The last epidemic gave us the Roaring ’20s—and the Klan.

“There’s a pretty direct connection coming out of the [World War I] experience plus the influenza epidemic and the kind of social life of the 1920s that we tend to think of—even given Prohibition. You can read correspondence—especially diaries from when the social distancing programs and cancellations and closures took effect—where people said one, they were fearful. And two, they really longed for social interaction. They felt sad. They didn’t know if they’d wake up the next day, or if they’re going to get sick and die. People came out of it wanting human connections. That included the rise of civil society organizations. But also terrible things, rooted in xenophobia ... [such as] the rise of the Klan. Lots of gatherings in the ’20s were not for good. How social relations will change is wide open in this moment. It’s pregnant with possibility.

“The 1920s were characterized by a series of recessions and a series of huge social dislocations; 1919, globally, is one of the years of the most mass protests. There’s the great steel strike in the US, the Boston police go on strike. There are a lot of reasons to think that meaningful reform and social dislocation will come out of this—that may be a silver lining or may be something that people dread. But I think it’s a reality that we should all be prepared for.”